Weak competitive intensity and regulation that do not foster innovation have thus far slowed the adoption of new technologies in the Israeli economy. Israel must now brace itself for inevitable ‘Creative Destruction’ processes that will coincide with global automation trends

In recent decades, Israel has established itself as a global hub of innovation that excels in tech development and produces groundbreaking companies. We often cite the extraordinary accomplishments of yet another Israeli company that has developed a new, revolutionary product; nevertheless there seems to be a significant discrepancy between the advanced high-tech industry and day-to-day life in Israel. Most people in Israel do not feel that they are living in a ‘technological’ country when they are on their way to work, when dealing with bureaucracy, or when shopping at chain stores. This is more than just a feeling – substantial sectors in Israel, such as transportation, commerce, construction, education, and public services, are still lagging behind other Western countries. A Londoner, for example, might take advanced services for granted, such as taking an Uber, a contactless or cellphone payment at a coffee shop, broadband browsing, efficient online communications with public entities, and fast, efficient construction.

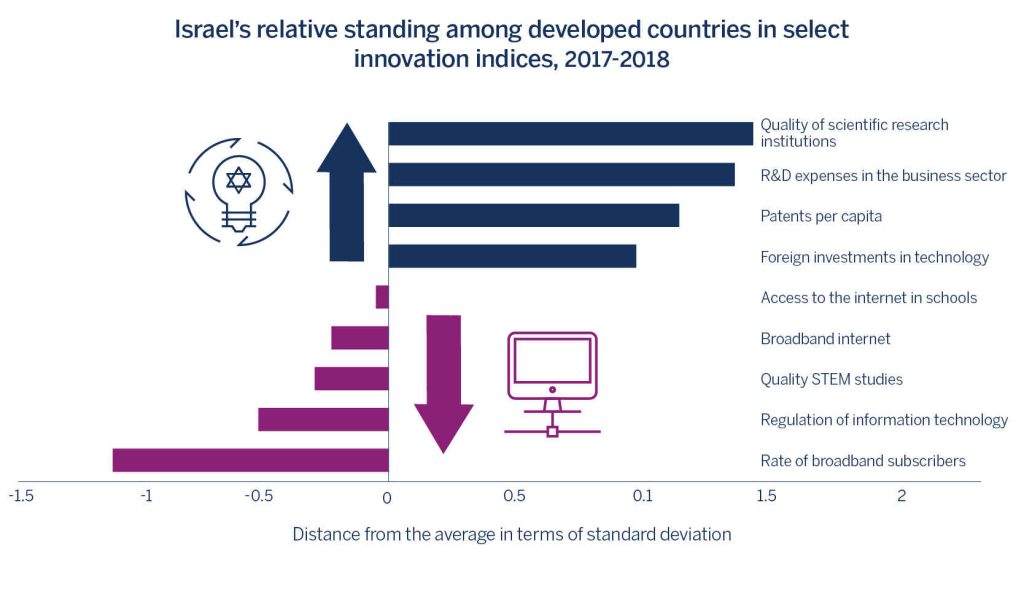

Comparative data indicates that Israel excels at creating innovation – meaning technology development – but is falling behind developed countries in the consumption of innovation – meaning technology assimilation. For example, in the Global Competitiveness Index published by the WEF (World Economic Forum), Israel has consistently been a leader in a number of parameters that reflect the strength of its innovation ecosystem, such as its heavy investment in R&D and quality scientific research. On the other hand, in other parameters included in the index that characterize innovative economies, such as digital infrastructure and the technological capabilities of its population, Israel is coming up short in comparison to other developed countries (see diagram 1).

A prominent sector where there is a substantial discrepancy between technological developments and the penetration of innovative technologies in people’s day-to-day lives is transportation. Despite impressive Israeli developments – including apps like Waze, Moovit, and other groundbreaking products like Mobileye – transportation solutions made available to the Israeli population are very limited.

We believe that increasing the penetration of advanced technologies into day-to-day life in Israel is critical for economic prosperity and for improved quality of life. If Israeli innovation doesn’t break through the confines of the high-tech industry, this innovation will only be accessible to small, distinct segments of the population. In our previous annual report, we pointed to the need to increase the number of employees in innovation-driven companies – so that more employees would benefit from high productivity, high pay, and challenging work. In this chapter, we will discuss the need to expand Israeli innovation even further, to function as an engine to improve the lives of its population as a whole. To this end, Israel must progress from a startup nation to a smartup nation – a smart and technological economy that excels both in developing innovative technologies and in implementing them in all aspects of life.

The importance of this change becomes even clearer in light of the fast-paced technological changes taking place in all fields of human activity: technological innovation spurs new products and industries, but at the same time, makes existing industries obsolete. The Israeli economy is not immune to these processes, as evidenced in difficulties that several business sectors are currently facing. Consequently, the Israeli government must lay the necessary groundwork to harness new technologies to improve the quality of life in Israel and to enhance the prosperity of its business sector.

In this chapter, we will discuss the origins of the discrepancy between Israel’s capabilities in technological development and its ability to adopt and assimilate these developments in the local economy, and we will present viable paths to bridge this gap. In particular, we will describe the Innovation Authority’s policy to increase the link between Israel’s high-tech industry and its other business sectors, and we will discuss the importance of supportive regulation both for the development of innovative technologies and for their assimilation into the economy. In the final section of the chapter, we will present the vision of several government ministries on that ways that innovation would upgrade their respective fields.

Source: WEF1Israel’s standard score among a group of 29 countries that meet the definition of “developed economies” according to the Monetary Fund OECD membership. All parameters are updated to reflect 2017-2018 data, except for the regulation of information technologies, which is updated to reflect 2016 data,2World Economic Forum. (2018) ,3World Economic Forum. (2017)

Technology adoption in the Israeli economy

Why isn’t Israel’s economy technology-driven as a whole, despite its flourishing high-tech industry? In this chapter, we will hone in on two possible causes: the nature of competition in the business sector, and Israel’s regulatory environment.

In recent years, weak competition that characterizes many branches of Israel’s business sector has been at the heart of public discourse regarding the cost of living, but it has had another consequence: it impedes investment in innovation. Weak sectorial competition, especially with leading actors across the globe, reduces the incentive to bolster productivity through investing in innovation and technology, and hinders consumer access to advanced, inexpensive services and products.4It is important to note that in certain sectors, fierce competitiveness could also have a negative impact on innovation incentives, because companies’ profit margins are very low.

For all intents and purposes, Israel is a small ‘island economy’ far from global supply chains. This results in relatively low exposure of many local companies to global competition with innovative companies, because the feasibility of launching operations in Israel – whether via imports or via local presence – is low.

The small size of Israel’s economy and its geographic isolation also affect the intensity of competition in sectors that from the outset have very low exposure to imports, such as construction, infrastructure, banking, communications, and trade in certain products. In these sectors, which generally offer low profit margins relative to international shipping costs, a short shelf life, natural monopolies, and singular local regulation, manufacturing and consumption take place in close geographic proximity. In economic jargon, these sectors are called non-tradable sectors. In large geographic markets, such as the US and the EU, it is economically feasible for many actors to operate in these sectors. In contrast, in Israel, a small, isolated economy, the economic incentive for new competitors to enter these sectors is weak; as a result, competition is limited.

Another component that impacts the adoption of innovation is the regulatory environment. As we will detail in the following discussion, regulation plays a key role in either encouraging or hindering the assimilation of technological innovation in the local economy. Regulation can block competitors dependent on innovative technology from entering a certain market, or it can make it difficult for existing competitors to provide services and products using innovative technologies. In the financial sector, for example, regulatory restrictions, stemming from financial regulators’ desire to ensure the stability of the financial system and protect consumers, mean that Israelis do not benefit from innovative financial services as people in other countries might. Regulation can also impact the level of technological innovation in services that a variety of public entities provide, such as legal services, transportation services, and vital utilities like water, electricity and others.

However, an analysis of current technological trends indicates that we are at the crux of processes that are slated to rock existing markets, and which will not spare the Israeli economy. Firstly, the rapid digitization and automation of products and services is diminishing the importance of geographical distance, and is transforming Israel from a distant island economy to yet another location in the global village that is exposed to fierce competition. Any product or service that can be digitized, such as books, newspapers, or even certain financial services, is becoming available for sale and consumption from any location.

Secondly, tangible consumer products are undergoing and will continue to undergo a radical transformation in the business models for their supply – from the streamlining of logistic systems, to delivery by drones or autonomous vehicles, to the home manufacturing of products by use of 3D printing. Just over the course of this past year, we have seen long- established retailers in Israel cave to competition posed by online, international businesses offering inexpensive products and low shipping costs.

Thirdly, the penetration of innovative technologies in highly regulated, ‘local’ fields, such as transportation and finance, is changing the rules of their usage. In particular, innovative, fast-moving startups are quickly becoming potential contenders for banks, credit card companies, and public transportation providers worldwide. Ultimately, it will become impossible, and undesirable, to halt their penetration to local operations in Israel.

Lastly, problems in public and vital service sectors in Israel are growing, and the pressure to solve these problems is increasing. Israelis, who are more exposed to standards provided in developed countries than in the past, are now demanding trains that arrive on time, orderly mail delivery, reduced traffic congestion, and other basic vital services.

These trends will expose companies across all business sectors in Israel to global competition, and will increase pressure on regulators to adapt the rules to a new era. We believe that a response focused on fortifying defenses will lose efficacy over time, and will not serve the interests of the Israeli public. To the contrary – Israeli companies should be offered assistance in facing global innovation-driven competition, and regulation should be adapted to new technologies and to global regulatory trends.

In recent years, the Israeli government has been working to bridge the gaps in digitization that have been accumulating for decades – but this is not enough. Other developed countries are already gearing up to derive maximum benefit from technologies of the future, particularly from AI. Last year, many countries presented national programs aimed at harnessing developments in the field of AI in order to bolster productivity and improve wellbeing, while addressing the implications of these technologies in the workplace. Israel is facing a significant challenge on its way to becoming a smart technology economy: the gap must be bridged quickly in order to secure Israel’s future standing among the advanced economies of the world. The duality that has existed thus far between the innovative high- tech sector and the rest of the economy, which has been slow to adopt new technologies, is not sustainable.

How can we effect change?

first and necessary step in this direction is to reinforce the link between Israeli high- tech companies and other sectors in the economy. Currently, Israeli high-tech companies primarily deal with global markets, and have few local customers. As a result, the extraordinary potential of Israeli innovative developments in improving products and services offered to the local population remains unfulfilled. Encouraging collaborations between Israeli high-tech companies and Israeli organizations in the business and public sectors would benefit both sides: local organizations would be exposed to innovative technologies and would assimilate such technologies, while high-tech companies would work on upgrading their products ‘close to home’, thus improving their starting point in the global competitive market.

The Innovation Authority has taken on this task, and is already acting to fulfill this vision. The Authority’s new track for supporting pilots is encouraging Israeli high-tech companies to test or demonstrate their products at a range of sites in Israel (see margin text). The Authority is working in collaboration with several government ministries that have an interest in fostering the assimilation of innovation in their respective fields. These ministries are contributing funding and regulatory approvals for the demonstration of innovative technology as needed. At the same time, the Authority is providing support for the development of technologies aimed at addressing challenges in Israel’s public sector, in collaboration with the national Digital Israel Initiative by the Ministry of Social Equality.

The direct effect of government regulation on innovation is becoming increasingly significant with the increasing pace of technological changes; as a result, it is necessary to take further action in the field of regulation. This challenge – balancing public protection and guaranteeing market fairness with advancing innovation – is also becoming increasingly complex. Innovative technologies are generating new human and business activity and are completely transforming market dynamics. Regulators must promptly create, change, enforce and communicate rules to the public.

The present rate of regulator activity is a central limitation in the traditional regulatory climate. Policy cycles take from 5-20 years, whereas a startup can develop into a global company in a matter of months.5Turley, M., Eggers, W. and Kishani, P. (2018, June 19). The future of regulation – Principles for regulating emerging technologies Other fundamental regulatory restrictions include regulatory barriers that do not communicate with one another (unlike technologies that operate across sectors), and a tendency to rely upon input such as technical specifications that only apply to a particular technology, instead of striving for performance and results.

Several developed countries are currently testing with innovation-supporting regulation, and are creating new paradigms in an effort to overcome these restrictions. In the US, for example, the nHTSA (national Highway Traffic Safety Administration) is attempting to create regulation for testing autonomous vehicles that updates periodically in accordance with technological developments. In 2016, it published rules that permitted the testing of autonomous vehicles on public roads. In 2017, these rules were already updated in response to new gathered data and newly developed technologies,6Crowell & Moring. (2017, September 17). DOT and nHTSA Release new “2.0” Guidance for Automated Vehicles. Lexology and are expected to be updated again in the future. In Israel, the Ministry of Transport recently began working on the regulation of autonomous vehicle testing and on the regulation of additional smart transportation technologies.

Another widespread paradigm is the development of trial and error mechanisms for industry, called a regulatory sandbox. A regulatory sandbox

is a controlled environment that allows entrepreneurs and companies to test products, services or business models, without adhering to all existing regulatory requirements. They often operate in collaboration with government, private companies, and academic institutions. Many countries currently operate such regulatory sandboxes, especially in the field of financial regulation. In Israel, the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Justice are examining the development of a similar trial and error environment for the fintech sector (see margin text).

Regulation can also directly encourage innovation by setting standards that incentivize the business sector or citizens to adopt innovative technologies. This is a commonly held practice in the energy and environmental sectors, where many countries set targets for reducing emissions on the one hand, while setting targets for the penetration of renewable energy on the other. In Israel, the Ministry of Energy is currently taking this approach to increase the penetration of renewable energy

and the use of less polluting vehicles, such as electric vehicles.

At the same time, the indirect effects of the regulation of innovation are no less remarkable. In Israel, inadequacy in ease of doing business is frequently cited as one of the most notable obstacles for growth in the country today. According to the World Bank Ease of Doing Business index, Israel was ranked 54th in 2017, after an accumulative drop of 21 places in the past five years. The Israel Business Environment Improvement Committee appointed by the Ministry of Finance Accountant General identified a series of problems in government activity that increase the bureaucratic burden placed on the business sector, such as inconsistency and lack of government coordination for improving the business environment, and inadequate mechanisms for creating routine dialogue with the business sector. The Committee stated that “Rapid adaptation to change, innovative thinking, and the adoption of progress, are critical for a business to maintain its competitive edge in particular, and for Israel’s business sector to maintain this edge over other countries in general”.7The Ministry of Finance Accountant General. (June 2018) The Israeli government recognizes the magnitude of this issue and has begun to reduce the bureaucratic and regulatory burden, but it is critical to establish firm policy to keep up with other countries.8A five-year plan has been implemented by the Prime Minister’s Office to reduce the overall regulatory burden in an effort to streamline regulation and to cut the cost of government bureaucracy by 25%. The Israel Business Environment Improvement Committee has also recommended the establishment of a senior general management committee headed by the Accountant General that will integrate operations to improve the business environment, and will advance a uniform applicable policy from an economic and business standpoint. Another central recommendation is to advance the establishment of a government portal and a personal digital space for businesses

The Innovation Authority has also begun advancing regulation that fosters innovation. In the context of an emerging collaboration with the WEF (World Economic Forum), Israel is slated to join the C4IR network (Center for the Fourth Industrial Revolution) aimed at establishing and sharing best practices in the field of innovation regulation, with an Israeli Innovation Authority center working with local regulators to establish and adopt regulatory rules for future technologies.