Israeli high-tech continued to break investment records even during the Covid crisis. Alongside the industry’s maturation, the number of new startups is declining sharply, the number of seed rounds is stagnating, and the Innovation Authority’s budget has been eroded. How will these changes influence the industry’s future and what can the government do to preserve Israel’s competitive advantage?

The Israeli high-tech industry has enjoyed significant growth and prosperity in recent years. Among others, this trend is reflected by the level of capital raised successfully by local startups, the scope of exits, and in the sector’s contribution to Israeli exports and to employment. The outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic in early 2020 was accompanied by concern that the global crisis would also have an adverse impact on the Israeli high-tech industry. However, despite the pandemic, the industry continued to grow, evidence of its resilience and its ability to respond rapidly to emerging opportunities. Although a slight decline was registered in the overall capital raised by Israeli high-tech companies during Q2 2020, the industry recovered later in the year, eventually growing by 20% compared to 2019.

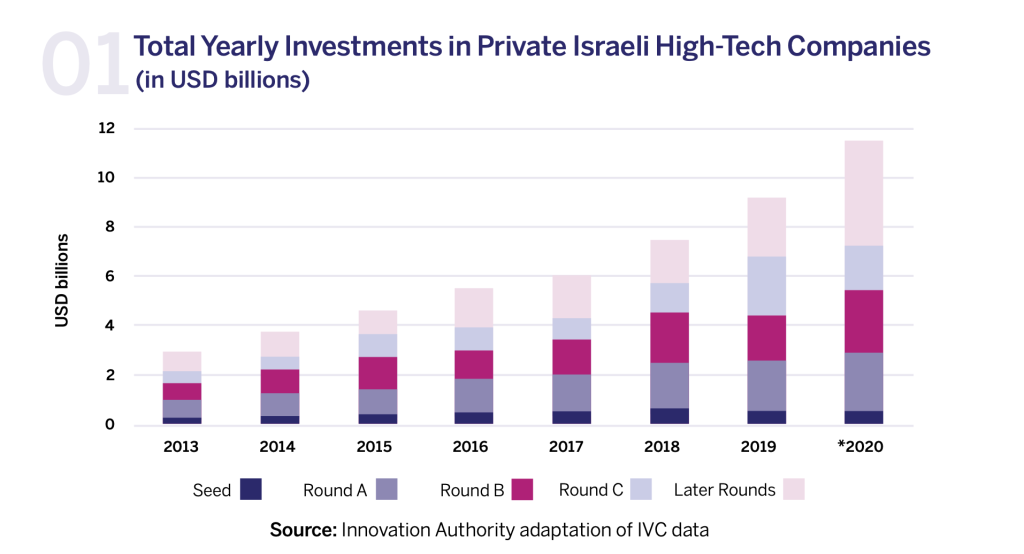

Investments in Israeli startups totaled USD 11.5 billion in 2020 – four times the level of only a decade previously.1According to IVC data. In 2020, the average and median size of Israeli technology companies’ funding rounds grew by 10% and 8%, respectively. Nevertheless, most of the growth in Israeli startup investments stemmed from an increase in late-stage funding rounds, some startups raising unprecedented amounts of several hundred million dollars in every round. Cyber and FinTech were the sectors of Israeli startup attracting the most investment in 2020, raising capital of USD 2.9 billion and USD 1.7 billion, respectively.

The digital health sector – as a direct result of the Covid crisis – held the second-largest number of funding rounds (after the cyber sector). This sector became especially popular and showed marked global demand. Another noteworthy field attracting investment interest in 2020 was that of smart mobility where approximately 60 companies raised USD 1.3 billion.2According to SNC data. It should also be noted that Israeli companies in all high-tech sectors using AI-based technologies raised over USD 4 billion in 2020, in keeping with the recent growing trend of investing in these technologies, as well as their integration in a wide variety of other fields.3According to IVC data.

The state of the Israeli high-tech industry during the Covid-19 pandemic also compares favorably from a global perspective. In the US, for example, while the total scope of capital raised by high-tech companies increased by 10%, the total number of funding rounds dropped significantly in comparison to 2019, particularly during ‘seed’ and ‘A’ rounds – 18% and 10%, respectively. Europe also experienced a significant decline in the number of early-stage investment rounds in 2020, with a 6% decrease in seed rounds and a 12% decrease in the number of ‘A’ rounds across the continent.4Innovation Authority adaptation of CB Insights.

Investments in startups have quadrupled within a decade. Cyber and digital health were the leading fields in the number of funding rounds in 2020.

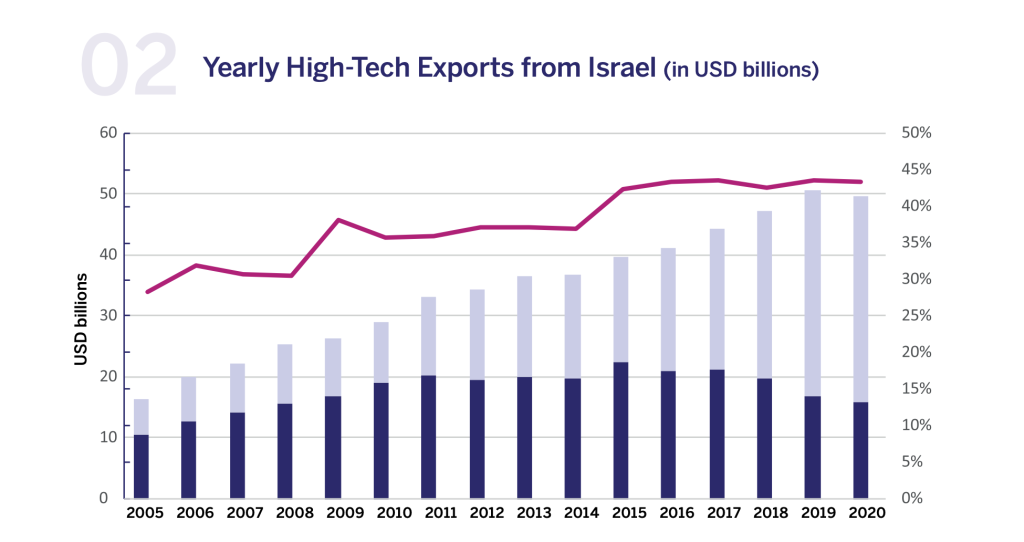

Macro-economic data substantiates the significant role that the Israeli high-tech industry continued to play in the country’s export activity, estimated at roughly 43% of all Israeli exports (45% when excluding diamond exports). The data pertaining to the high-tech sector itself clearly reveals that export of services such as software, was not adversely impacted by the Covid-19 crisis, while the industrial sector’s 2020 exports decreased by USD 1 billion.5High-tech services sectors include programming, data analysis, and R&D, while industrial sectors include pharmaceutical, electro-optic, aerial, and outer space companies. The differences between the diverse types of high-tech companies will be discussed in greater detail in the next chapter.

Source: Innovation Authority adaptation of CBS data6Plates: Exportation of commodities according to their technological strength (Israeli foreign trade, January 2021, Plate 17); Exports of services, December 2020 (Plate 2); Summary of Balance of Payments (Plate 1); and a foreign trade presentation (from the Israel Foreign Trade Announcement, Commodities in 2020).

Fewer new startups and stagnation in seed investments

From 2010 to 2014, the number of new startups established in Israel grew markedly, a phenomenon which stemmed from several factors. During those years, significant obstacles in the process of establishing startups were either removed of reduced, including a significant reduction in costs, ongoing improvements in cloud computing capabilities, and the deployment of cellular internet infrastructure that is faster than some of the more advanced “generations”. The growth of the mobile application market and the launch of various accelerator programs designed to help new startups grow have also influenced this trend.

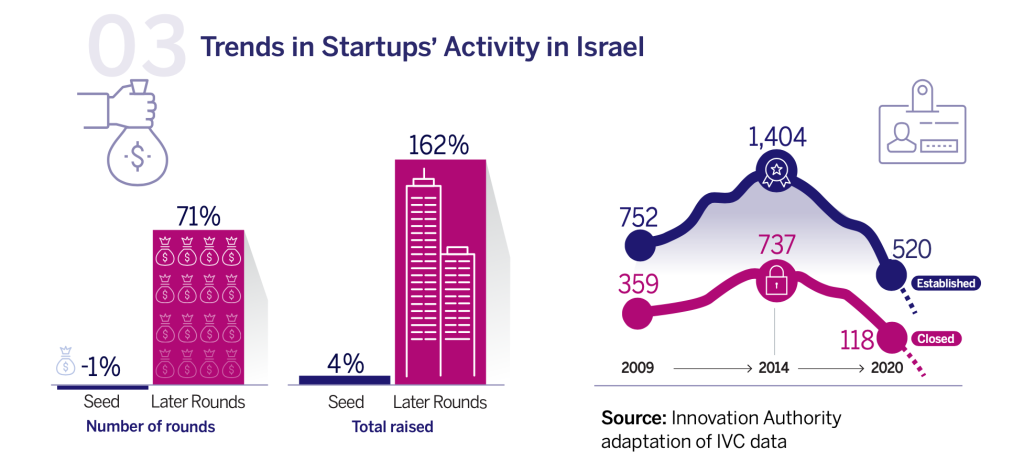

This important metric has declined significantly in recent years however, raising the question as to whether the Israeli ‘Startup Nation’ era has come to an end. Within five years, the number of new startups being established in Israel has decreased from approximately 1,400 in 2014 to about 850 in 2019, and it is estimated that only 520 new startups were established in Israel during 2020. A significant amount of the opening and closing data is received late, sometimes years later. In light of this fact and given the possibility that the corona period led to changes in entrepreneurs’ behavior, it is difficult to precisely estimate the number of companies established in 2020, therefore the known data is presented rather than the forecast. However, according to estimates, there is an expected decline in the number of new companies established in 2020 compared to 2019. Specifically, the number of new startups established in Israel during the past two years is similar to that of a decade ago although the country’s local innovation and technology ecosystem has grown and developed over this period. It is important to note that we still do not have complete data about the effects of Covid-19 on the number of new companies established during a year that was characterized by high unemployment rates across the Israeli economy. Once complete, the findings will also reflect trends pertaining to disruptive innovation-seeking sectors, such as tourism and retail.

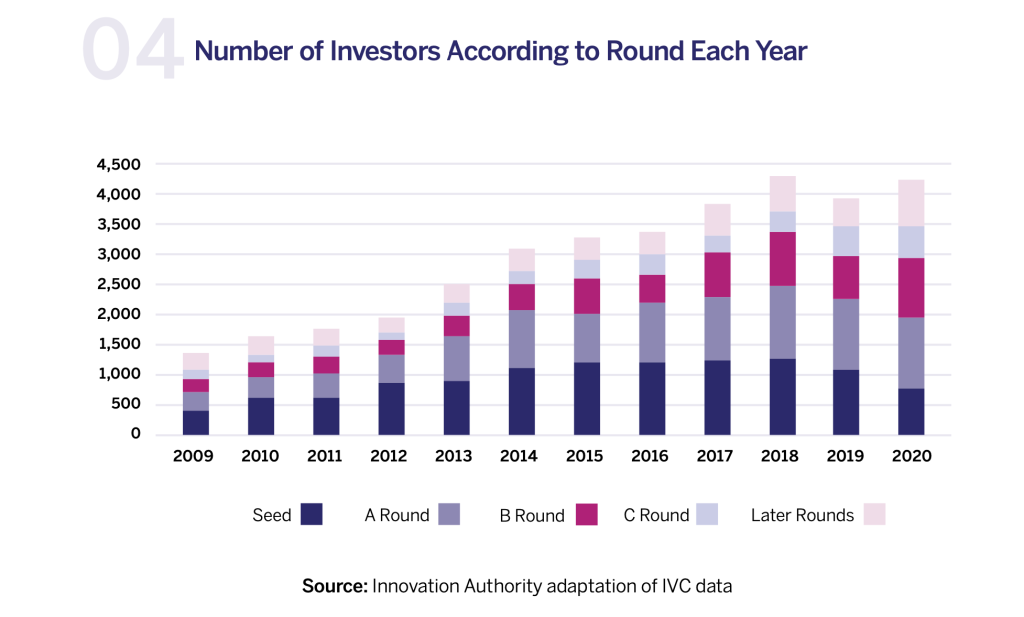

In addition to the decline in the number of new startups, the number of funding rounds in seed stage startups and the average investment in these companies have also stagnated since 2015. In contrast, during the same period, the number of Round A investments in startups doubled from 220 rounds in 2015 to approximately 400 rounds in 2020 and the average scope of each investment round increased. The growth in Round A investments and the parallel decline in the number of startups going out of business each year may be an indication that although fewer new companies were established, the quality of those companies established led to an increase in the number of companies that succeeded in raising later-stage funds after the seed round. 7Details on government response to the challenge of investments in early-stage companies which encountered hardships due to the Covid crisis, appear in the ‘Fast-Track’ Grants Program Box (Chapter 3).

A closer examination of early-stage funding rounds reveals a decline in the number of investors taking part in these rounds in the past two years, especially in the seed stage. This finding, along with the ongoing stagnation in the number of seed rounds presented above, has led the Authority to launch its ‘Hybrid Seed’ program. The goal of this program is to increase the number of potential investors involved in the seed stages, to increasingly focus the R&D Fund’s resources on early-stage funding of accelerator companies, and to encourage quality investors to participate in earlier stages via the Angels Law that will be discussed below.

When seeking to discern the various reasons for the declining rate of new Israeli startups, it is important to note that the decline in the number of new companies being established preceded the decline in the number of companies that closed and the lower number of investors. Accordingly, an examination of entrepreneurial activity is also worthwhile. The rise in average salary in the high-tech sector creates an incentive for employees to continue working in senior managerial roles rather than taking a risk in the world of entrepreneurship.8According to CBS data, the average salary across high-tech sectors grew by approximately 44% between 2010 and 2019, while the average salary across the general Israeli economy increased by only 28% during that same period (Plates depicting salaried positions and average salaries in high-tech). In addition, the growth in the number of international development centers in recent years (close to 400), enables employment in challenging fields at the forefront of worldwide technological innovation, and at higher pay levels than the average high-tech salary.9An examination held by the Finance Ministry’s Chief Economist found that in the high-tech sector in Israel, the average salary of employees working for foreign companies was roughly 8% higher than for those working for Israeli companies. See: The Contribution of Multinational Enterprises to Labor Productivity: The Case of Israel”, OECD Productivity Working Papers, No. 11, OECD Publishing, Paris. With regard to the startups themselves, this increase in salary leads to competition that is difficult to contend with at early stages of their lifecycles, especially when up against other companies with significant resources.

In recent years, investments in more mature, advanced-stage startups have also increased. We are starting to witness the growth of Israeli unicorns10.A private company worth over USD 1 billion. These startups are the product of existing companies that have now reached maturation. While a welcome phenomenon, the sector’s maturation raises the question as to whether the downturn in the rate of new Israeli companies is causing the start of a “funnel” problem: Is the number of new growing and developing startups in Israel sufficient to sustain the country’s current levels of entrepreneurial and technological activity? Considering the high-tech sector’s importance to the Israeli economy, a sharp decline in the number of new startups is too large a risk. In light of the change in the high-tech sector’s mix of companies, the Authority is currently examining which supportive tools and policy changes are necessary, both at the Authority specifically and in government departments in general, to ensure that Israel continues to be both a startup and a growth company nation.

More mature Israeli high-tech companies are enjoying larger stock issuing and funding

The decline in new startups has, in recent years, been accompanied by a parallel trend: the maturation of the local high-tech industry. Data indicates that more Israeli high-tech companies are raising increasingly larger sums, that their revenues are steadily growing, and that they are hiring increasingly more employees. If Israeli start-ups were previously sold while employing a few dozen employees or after raising a USD 20-50 million, and generally became development centers for a multinational corporation, today’s startups continue to grow as private companies with the help of significant capital raised from investors.

This most significant expression of this trend is the increased investments in advanced-stage startups. The total capital raised during later-stage funding rounds (from Round D onwards) grew significantly from approximately USD 1 billion in 2015 to USD 4.3 billion in 2020 – quadrupling in just five years. Most of the growth was concentrated in mega-deals: the number of transactions in which Israeli technology companies raised over USD 30 million grew from less than 20 in 2015 to approximately 100 in 2020. Over the same period, the number of transactions in which Israeli technology companies raised over USD 100 million in the private market grew from 3 a year to 20, with the highest growth in the frequency of these transactions occurring over the last 2 years.11According to IVC data

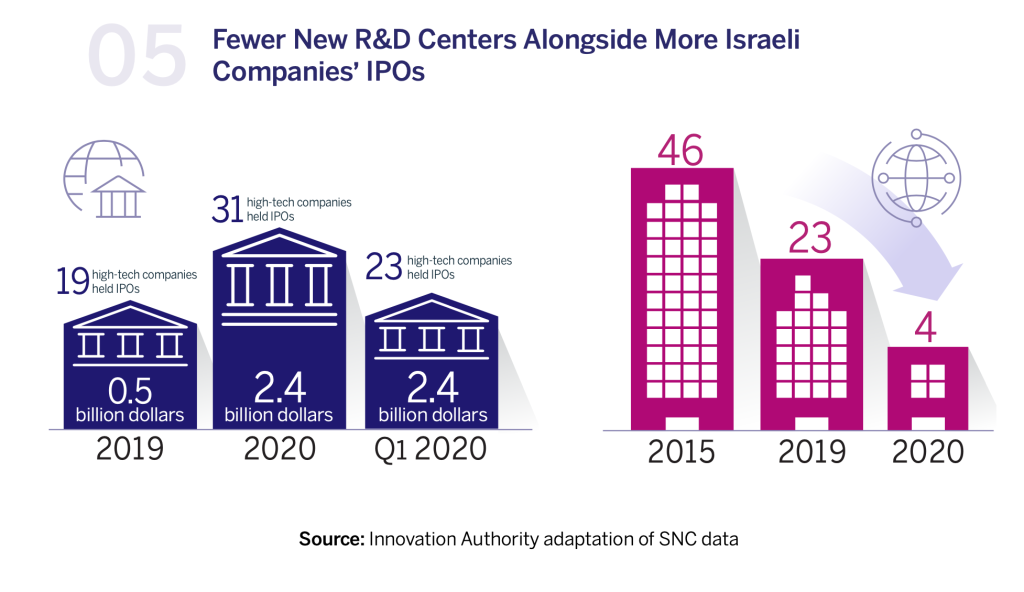

This trend has been reversed in the past year with an increase in the number of Israeli technology companies issuing stock. In contrast, the number of merger and acquisition (M&A) deals – previously the most common exit option for Israeli startups – has declined. According to IVC and PwC data, 20 Israeli companies held share IPOs in 2020, primarily on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange (TASE) and on Wall Street. During that period, 14 Israeli technology companies issued shares on the TASE and five R&D partnerships were issued.12The Tel Aviv Stock Exchange’s website

As the above graph clearly shows, the number of Israeli technology companies’ IPOs rose by more than 50% in 2020 compared to the parallel figure for 2019. Furthermore, the total capital raised by the companies during these IPOs rose five-fold, reaching approximately USD 2.4 billion, resulting in 2020 being a record year for capital raised by Israeli exits, despite the drop in the scope of mergers and acquisitions. The findings also reveal that 23 Israeli high-tech companies issued stock in the first quarter of 2021. Israeli companies are taking advantage of the global stock offering window and several other Israeli companies are already engaged in the IPO process and preparing to register and raise capital on various stock exchanges, indicating that this trend will continue in the foreseeable future.13Some of the companies enter the capital market via a SPAC mechanism that enables them to merge into a designated check company.

With respect to mergers and acquisitions, PwC reported a decline in the number of deals – from 67 in 2019 to 41 in 2020.14PwC Exits Report At the same time, the number of acquisitions made by Israeli high-tech companies has remained stable. Approximately 40 technology companies in Israel were bought each year by an Israeli buyer over recent years, thereby enabling Israeli startups to grow and expand, yet another sign of the industry’s recent maturation.

A decline in the number of M&A transactions led to a sharp drop in the number of new R&D centers. At the same time, there was a rise in the number of IPOs and SPAC transactions.

The Israeli high-tech industry is undergoing a transformation. More Israeli companies are preserving their independence rather than becoming R&D centers for multinational corporations as was customary in the past. These changes may alter the mix of companies and employers in Israeli high-tech. Israeli companies growing globally need administration, sales & marketing, operations, and production departments to maintain their growth. These roles are generally made redundant following acquisition of an Israeli startup and this shifting trend may therefore help retain these roles and provide new employment opportunities for Israelis. Although no such data has yet been gathered, it is possible that the ratio between core and peripheral technology employees in Israeli companies will rise in coming years as the result of the companies’ preference to maintain their independence and avoid acquisition.

Government support for innovation is critical to the maintenance of Israel’s significant economic leadership position

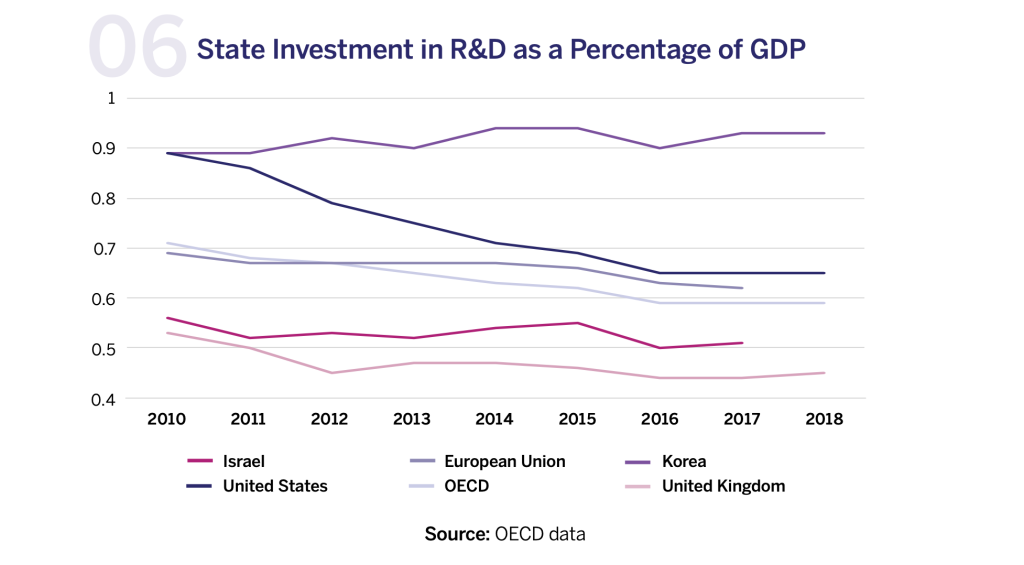

Israel continues to lead the world in R&D investment as a percentage of GDP. According to the OECD, this ratio stood at 4.94% in 2018, positioning Israel first in the world, followed by South Korea with 4.53%. In contrast, the level of state funding for innovation in Israel is lower compared to other countries – approx. 0.5% of GDP – and it is clear that most of the investments in the industry come from private funding sources within the business sector. In the EU and other countries, such as South Korea and the US, state investment in innovation stands at 0.6%-1% of GDP.

Moreover, the current erosion of the Innovation Authority’s budget in relation to the state budget, from a level of 1% at the beginning of the century to less than 0.5% today, equating to approx. 0.15% of GDP, is a worrisome trend. This long-term trend must be reversed if Israel is to maintain its position as a global leader in the field of innovation. Despite the maturation and prosperity of Israel’s high-tech industry, the market failures that characterize the industry are becoming more complex and there is greater need for private market participation in the risks inherent in seed and early stages, especially against the background of increased later stage investment. As mentioned above, other countries invest significantly in R&D. In the long-term, these countries may prove to be better prepared to navigate changes expected with future technologies and better equipped with R&D infrastructure suitable for their implementation.

In the past year, the Innovation Authority began using several new tools aimed at increasing sources of state funding for Israeli innovation. As part of the economic program for coping with the Covid-19 crisis and to help high-tech companies at growth and marketing stages contend with the period’s financial challenges, the Authority launched a new program in October 2020. The program, established in conjunction with the Finance Ministry, the Capital Market, Insurance, and Savings Authority, and the Israel Securities Authority, aims to encourage the institutional entities active in the local capital market to invest in Israeli high-tech companies in initial sales and growth stages. As part of the program, state guarantee is given to the investment portfolio of any institutional entity investing in Israeli technology companies.

The Innovation Authority’s investment committee decided to guarantee 2 billion shekels worth of investments in high-tech companies out of requests for total guarantees of 3.25 billion shekels for 10 institutional entities in the Israeli capital market. At the same time, a further program was launched during 2020, to help institutional investment entities set up technology research and investment departments and to develop high-tech investment skills.

These measures, pertaining to the Israeli institutional capital market, were implemented with a long-term objective of resolving the market’s failure to disconnect the Israeli capital market from the local high-tech sector. This program’s impacts are already evident with institutional entities increasing their direct investments, collaborations with venture capital funds, and investments in Israeli technology companies on local and foreign stock exchanges. This program may be a central factor in altering the structure of the local capital market and in diverting its focus towards technology fields (creating a “home bias” that characterizes local stock market overinvestment in local activity).

The Innovation Authority is planning further initiatives and legislative changes aimed at supporting opportunities and existing challenges related to the funding of innovation and Israeli high-tech companies. Some of these were presented as part of proposals for a government resolution published by the Ministry of Finance in July 2020 and address existing market failures in Israeli high-tech with the aim of assisting the creation of new companies and the growth of whole companies in Israel:

The New Angels Law: A proposed amendment to the existing Angels Law. The proposal added a new incentive program that will enable the alteration of share capital and the deferment of capital gains tax payments by investors for exits, so long as they funnel their exit profits into new investment in R&D companies. The goal of this proposal is to encourage additional investors from the high-tech sector to take a risk and invest their personal capital in startups. In many cases, it is private investors (angels) who invest in seed stage companies and this proposal aims to stimulate investor activity and investments during the seed stage using “smart and well-connected” capital.

Easing acquisition of foreign companies by Israeli corporations: As mentioned above, a large part of the growth experienced by Israeli high-tech companies operating as independent global corporations is facilitated by their acquisition of Israeli startups. The current proposal is to assist Israeli corporations interested in acquiring foreign companies in order to encourage inorganic growth and to attract resultant intellectual property, employment, and tax income to Israel.

Amendment of tax regulations on foreign loans to high-tech companies: The leverage ratio of Israel’s high-tech industry is significantly lower than that of other countries. Furthermore, loans are generally borrowed from a foreign lender and using a foreign entity owned by an Israeli company. Amendments are therefore required in tax regulations on foreign loans to enable Israeli high-tech companies to expand their activities in Israel, increase their available funding options, and build a significant local credit market.