The Next Quantum Leap of Israeli High-Tech:

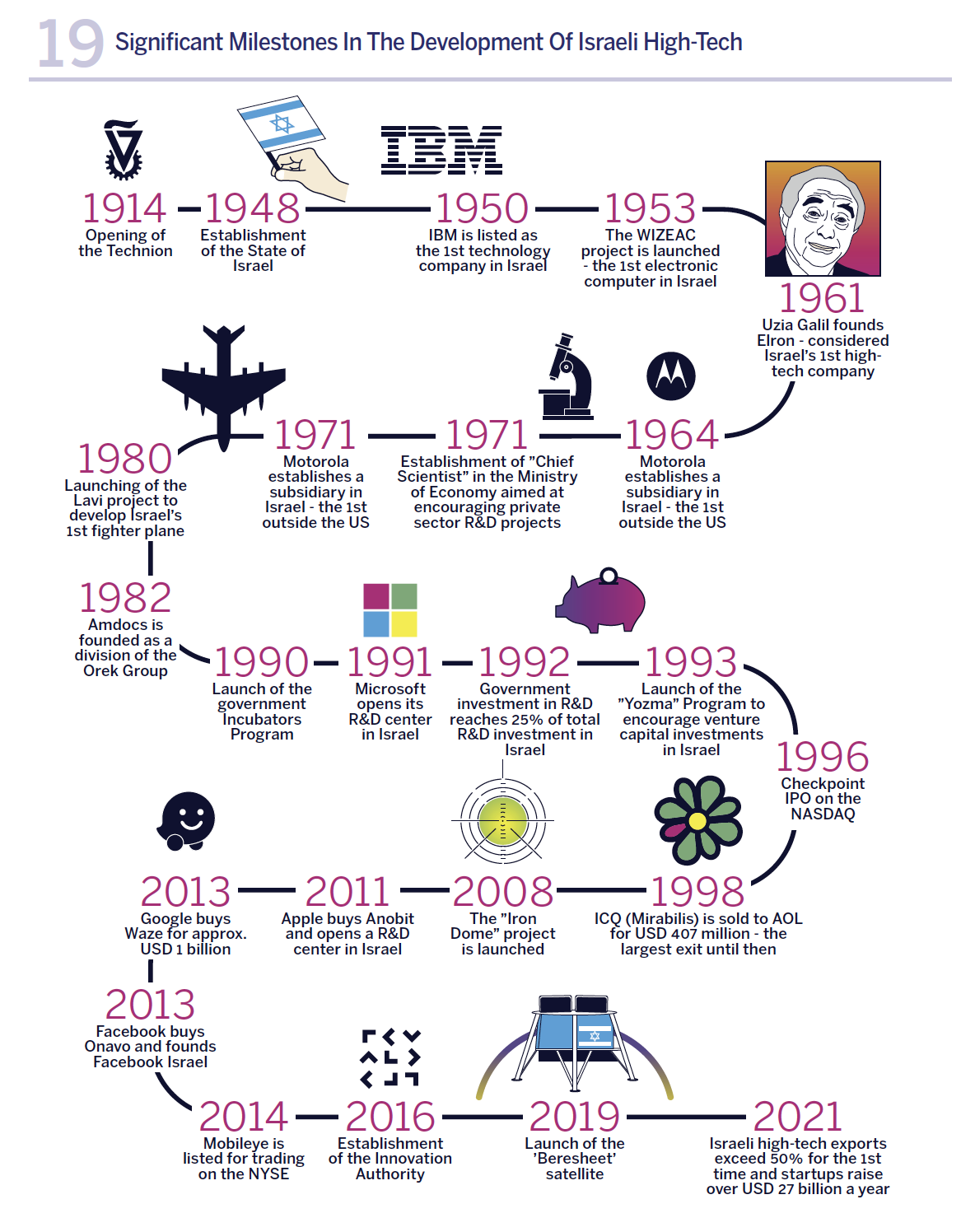

It seems as if Israeli high-tech has existed forever, but it is actually one of the younger sectors of the local economy. In a relatively brief period over the past few decades, Israeli high-tech has established itself as a significant factor in the local economy, not only contributing to employment, exports, and other important macro-economic indices. The Israeli economy has become largely dependent on the high-tech sector. Israeli high-tech has enjoyed accelerated growth in recent years, a phenomenon that is expressed by the emergence of Israeli technology companies that are not seeking a quick “exit” sale to multinational giants, that raise unprecedented sums of funding, and which go public and are traded on the stock exchange. Furthermore, these companies also employ large numbers of employees in Israel and overseas and enjoy large-scale sales revenues.

Israeli high-tech relies, among others, on excellent human capital, world-leading academic institutions, and venture capital investors that facilitate the development of local startups. Israeli high-tech also includes companies from the defense industry that are at the forefront of technological development and multinational corporations which develop innovative solutions in Israel while also serving as investors, buyers, and partners of local startups throughout the different stages of their existence.

The past two years signify a turning point for the Israeli high-tech industry that has now reached a more mature stage of its development. Among the current period’s characteristics are the large number of Israeli startups that have become public companies, and the Covid pandemic’s impact on the labor market. As a result, the challenges confronting the Israeli high-tech industry and the relevant solutions are also changing.

Since the inception of Israeli high-tech, the state has played an important role in removing obstacles and laying infrastructures to advance Israeli innovation. For example, in its very early stages, Israeli hightech contended with serious funding challenges. In response, during the 1990s, the government laid infrastructures critical for the growth of the Israeli venture capital sector via the “Yozma” program and strove to solve funding problems of R&D-oriented startups via programs that provide them with direct financial support. At the current point in time, Israel is home to an extensive and strong high-tech industry and funding difficulties have abated. These difficulties exist today primarily in the companies’ early life stages and in especially high-risk areas that are generally characterized by deep technologies, long “time to market” (TTM), or regulatory obstacles. This trend has been manifested in recent decades by a decline in the level of government expenditure out of total investments in Israeli high-tech from 25% at the beginning of the 1990s to less than 2% today. In other words, the private market has almost totally assumed the role filled previously by the state at the industry’s outset and has now become the primary funder of high-risk innovation in Israel.

Today, alongside the change in the Israeli innovation arena, the government’s role within the industry must also be revised in order to meet existing needs and to enable Israel’s next quantum leap. The goal is to enable Israel to preserve its position as a global technology leader while facilitating an improvement in the level of technological innovation available to Israeli citizens.

What are the Revised Needs of Israeli Innovation in the Current Era?

The Israeli innovation hub competes with other global hubs of innovation, that include cities or small countries such as Paris, Toronto, Sweden, Singapore, Switzerland, Boston, Berlin, Chicago, Seattle, and Ireland. Israel leads the group of hubs in metrics such as the number of young seed-stage startups, ranks second in the absolute number of high-tech employees, and fifth in the number of high-tech employees per capita. In contrast however, Israel’s ranking in other metrics has deteriorated e.g., the level of venture capital investments it attracts. According to ‘CrunchBase’ data, while the relative share of investments in hubs such as those in Berlin and Paris has grown in the past two decades, the share of venture capital investments flowing to Israel declined during the same period from 18% of total investments in the hub groups examined to 11%.

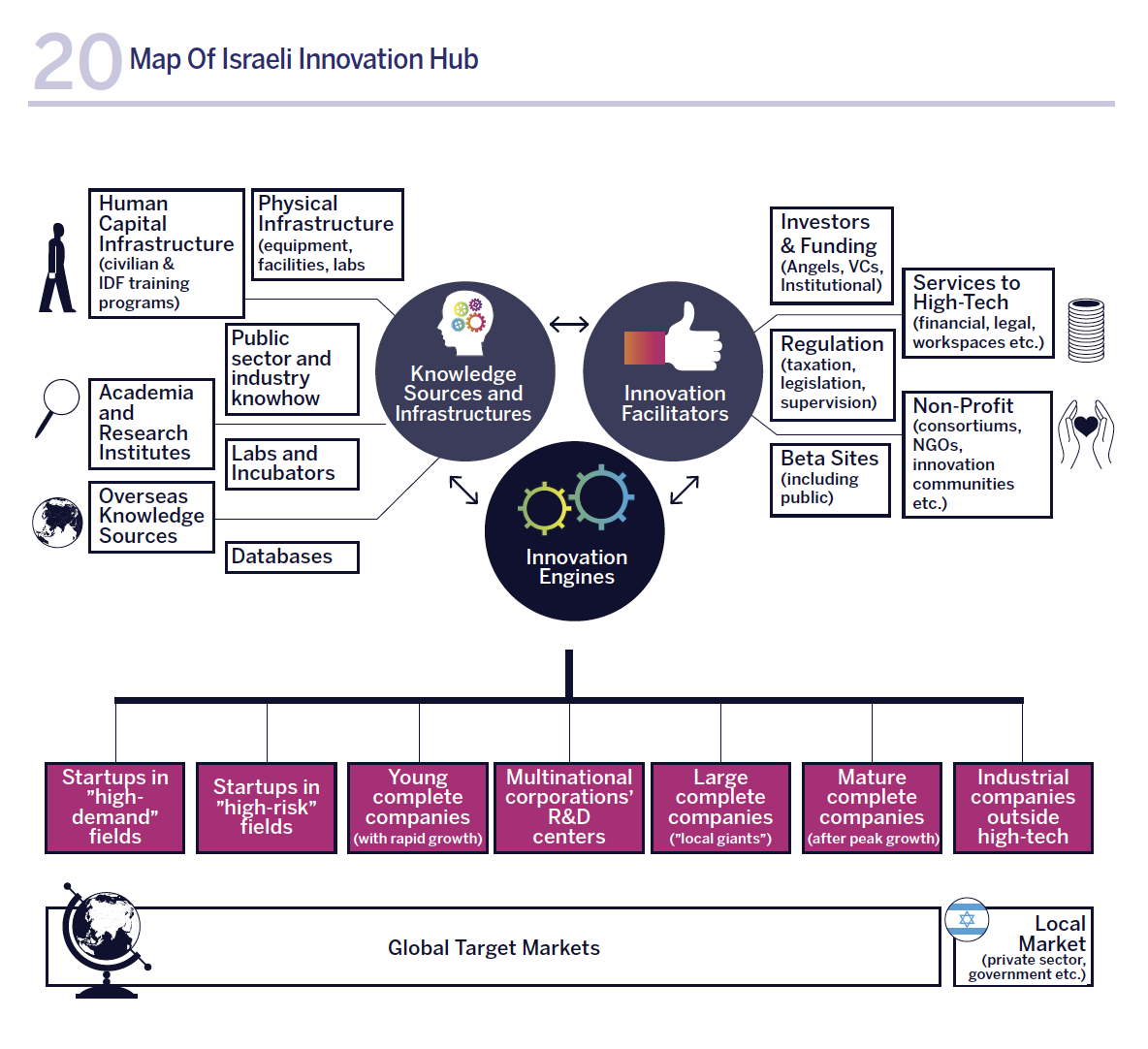

To ensure that Israel maintains its leading position vis-à-vis other global innovation hubs, solutions must be found for the challenges facing Israeli innovation. These challenges can be divided into two central groups: the first includes the current commercial needs of the Israeli high-tech industry and of the companies themselves. The industry consists of a diverse range of organizations including startups in “high-demand” and/or high-risk fields, growth companies, local giant companies, and multinational corporations’ R&D centers. The challenges relevant to the Israeli high-tech industry include, among others, a severe shortage of technology workers, guaranteeing readiness for future technology trends, reinforcement of the growing and whole companies in Israel, and exposing the companies to overseas markets.

The second group of challenges is related to connecting Israeli innovation to the local private and public sectors. A disparity exists today between the groundbreaking innovation developed by Israeli high-tech employees in Israeli and global companies, and the level of digital and innovative services available to the Israeli public. In other words, “the shoemaker’s son always goes barefoot”. In this sense, the Israeli public does not benefit from Israeli innovation in the course of its daily life. The challenges related to this issue include removing obstacles to enable the experimentation and assimilation of pioneering technologies in Israel, funding R&D and innovative infrastructures in companies that are not part of the high-tech industry and in the public and private sectors, encouraging innovation-based management in non-technology companies, assimilation of advanced technology in the economy, and training workers in the skills needed for engaging in innovation.

The solutions that will meet the updated needs of the industry involve players from all parts of the Israeli innovation ecosystem, including the “innovation engines” themselves i.e., the entities that engage in developing technologies (including startups, growth companies, R&D centers etc.). In addition, apart from the innovation engines, it is worthwhile to note the “innovation facilitators” – the institutions responsible for the infrastructures and services (including venture capital and other investors, different regulators, training entities etc.), and the sources of knowledge – organizations that create scientific, technological, or other unique knowledge that can be transformed into innovation. For example, academic institutions and research institutes or the end clients themselves who possess knowledge about their innovation needs. Connecting the entities that belong to these three groups generates innovation that is subsequently used by end clients in diverse Israeli and global target markets.

The Innovation Authority, as an advisory entity to the Israeli government in the fields of innovation, is also currently required to adapt itself to the new reality. As part of the new role the Authority is assuming, it is also updating its existing solutions’ offering, which until now, focused primarily on direct financial support for companies. The Innovation Authority’s role makes it a mediating entity that enables the achievement of the next quantum leap of Israeli innovation, for example, by addressing the economy’s significant challenges in the fields of housing and transportation. Later in this section of the report, we will present a detailed examination of two central challenges facing Israeli innovation: connecting Israeli technology companies to academia in order to ensure continued innovative R&D that enables their continued growth; and connecting Israeli innovation to the public and private sectors in Israel with the aim of enabling them to provide the Israeli public with advanced services. We will thereby gain an in-depth understanding of the problems and their significance, and present alternative solutions based on the Innovation Authority’s new strategy.

The Unrealized Potential of Israeli Technology Companies: Collaborations Between Industry and Academia

A significant proportion of the historical breakthroughs in the world of technology are based on research that originates in academia. In the research laboratories, scientists and researchers uncover new discoveries, the commercial application of which creates a new world of developments and progress. The prominent examples in Israel over recent decades are the Copaxone medicine developed by Prof. Ruth Arnon from the Weizmann Institute in conjunction with TEVA, and the computerized vision system for motor vehicles developed by Prof. Amnon Shashua from Hebrew University that led to the foundation of the Mobileye corporation.

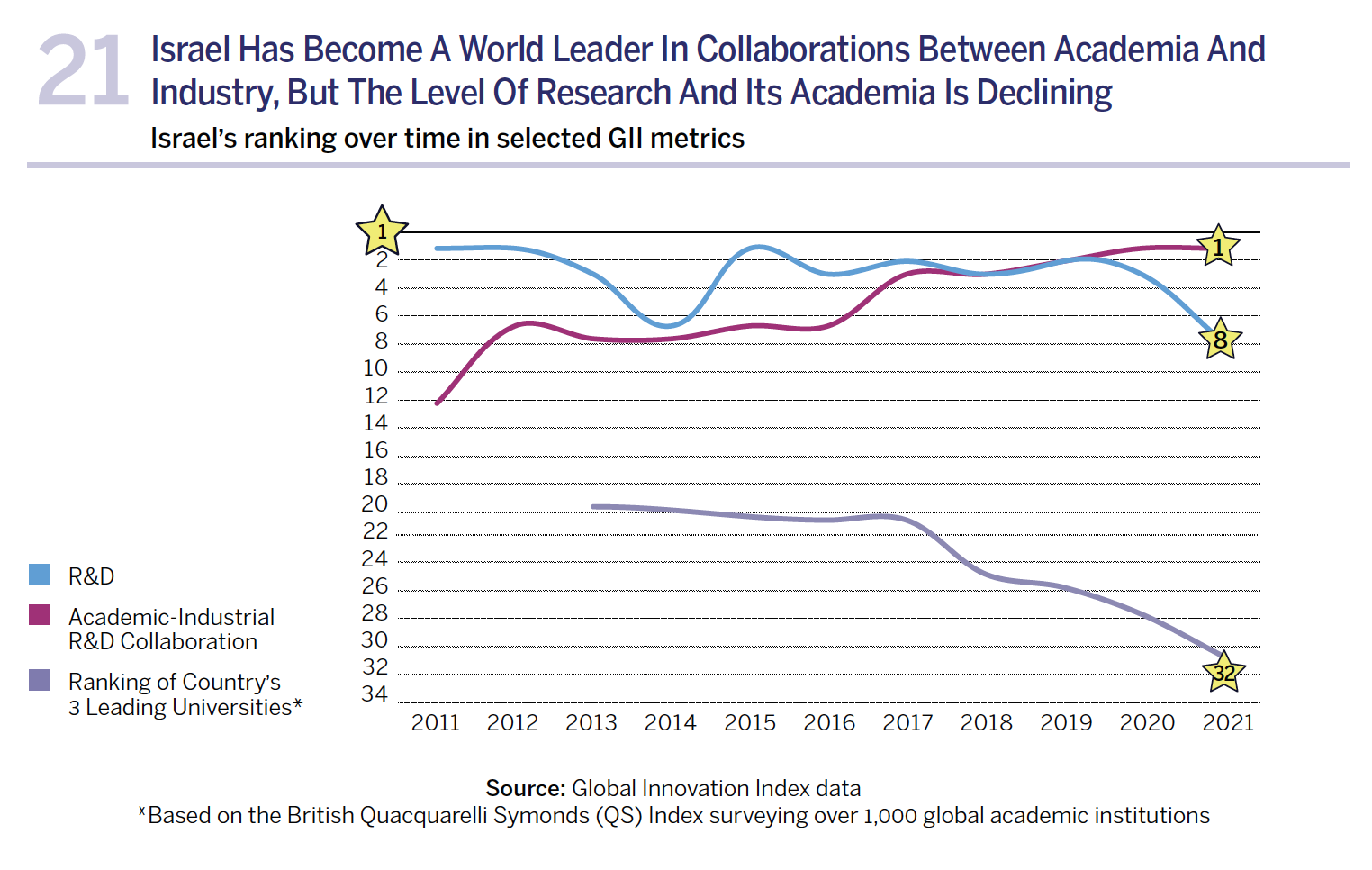

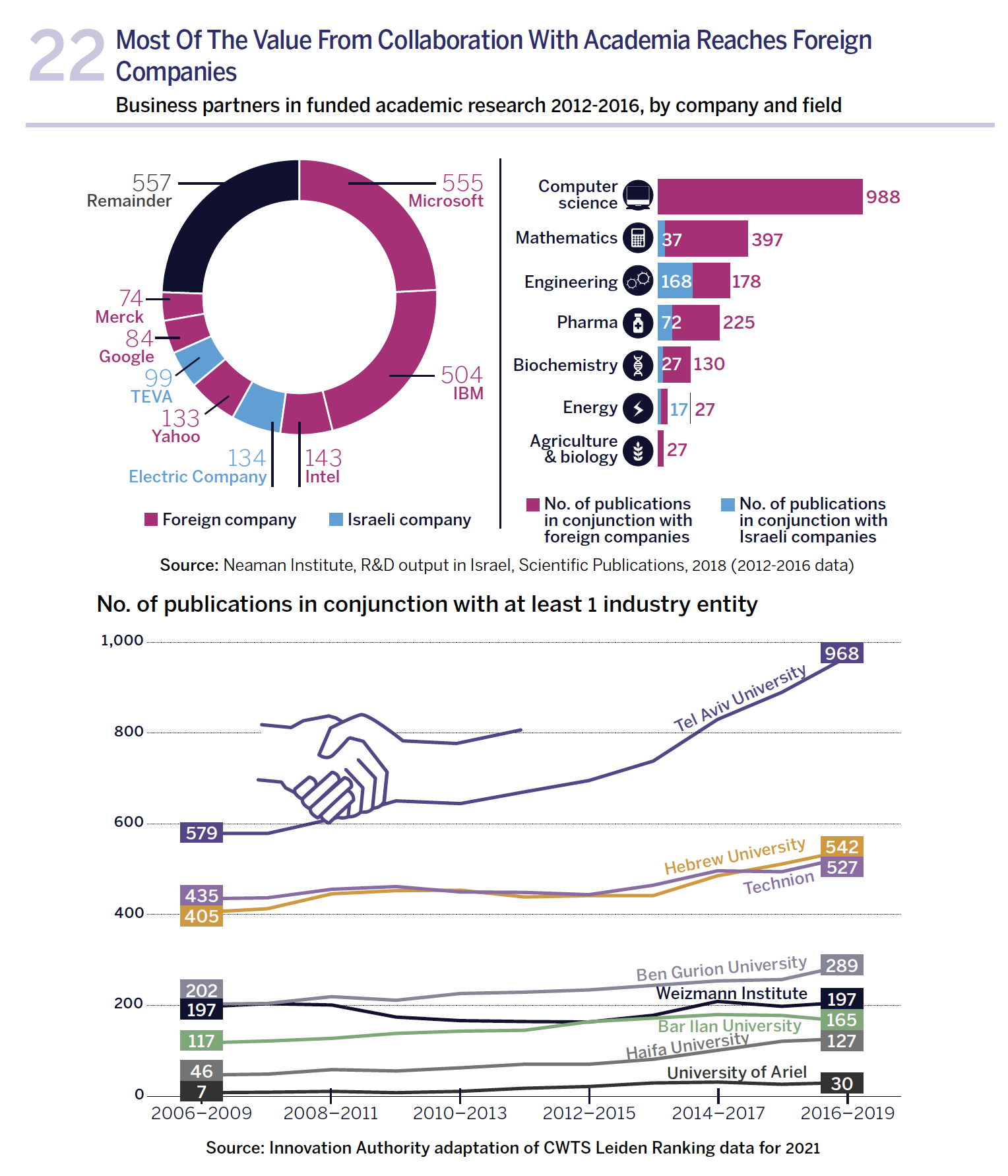

Overseas, the largest technology companies, recognizing the importance of collaborations with academia for their continued growth, strive to establish such collaborations, with some even maintaining their own labs in academic institutions. A look at Israel reveals a slightly complex picture. On the one hand, Israel is ranked first in the world in the field of collaborations between academia and industry according to the Global Innovation Index (GII). Nevertheless, an in-depth examination reveals that this flattering fact stems primarily from the activity of the foreign companies that operate development centers in Israel. IBM and Microsoft alone are responsible for half of the research collaborations. In total, 85 percent of the collaborations between industry and academia are undertaken by multinational companies.

In contrast, the local technology companies make almost no use of this avenue and focus instead mainly on internal organizational R&D that relies on the expertise and human capital at their disposal. The exceptions to this rule in Israel are the Israel Electric Company, TEVA, and the defense industry companies Rafael, Israel Aerospace Industries, and Elbit. One surprising finding is the small number of collaborations between Israeli companies and academia in the fields of computer science, the fields with most collaborations, comprising over 20 percent of academic research output in Israel.1See the report published by the Samuel Neaman Institute on the outputs of R&D in Israel: Scientific Publications – An International Comparison, 2021 (Heb).

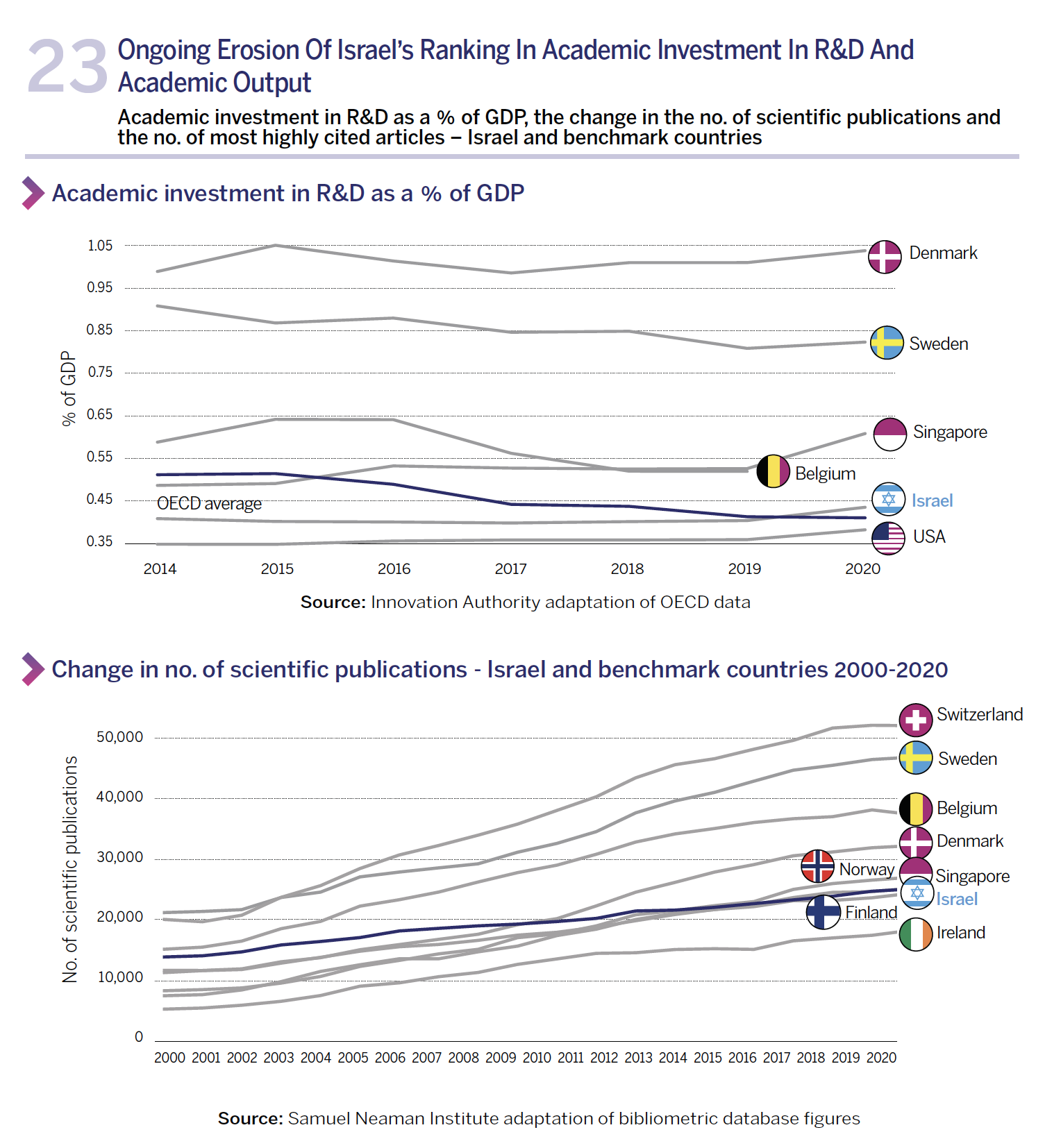

Israel ranks high (and is still improving) in the international index of per capita investment in R&D however, an opposite trend can be detected in Israel’s ranking in per capita academic investment in R&D (from 3rd in the OECD in 2006 to 26th in 2018) This is a long-term trend that indicates a significant erosion in the level of competitiveness of Israeli academia and may, in the decades to come, influence future developments on which Israeli high-tech will rely.

Strengthening the collaboration between academia and Israeli industry may prove to be a win-win factor benefitting both parties. On the one hand, Israeli companies may find academia to be a source of high-quality research human capital that can meet the needs of the industry which suffers from a chronic shortage of workers. On the other hand, this human capital from academia will expose Israeli companies to advanced knowledge and will enable them to make the next quantum leap and further extend their ability to continue being innovative and competitive on the global market.

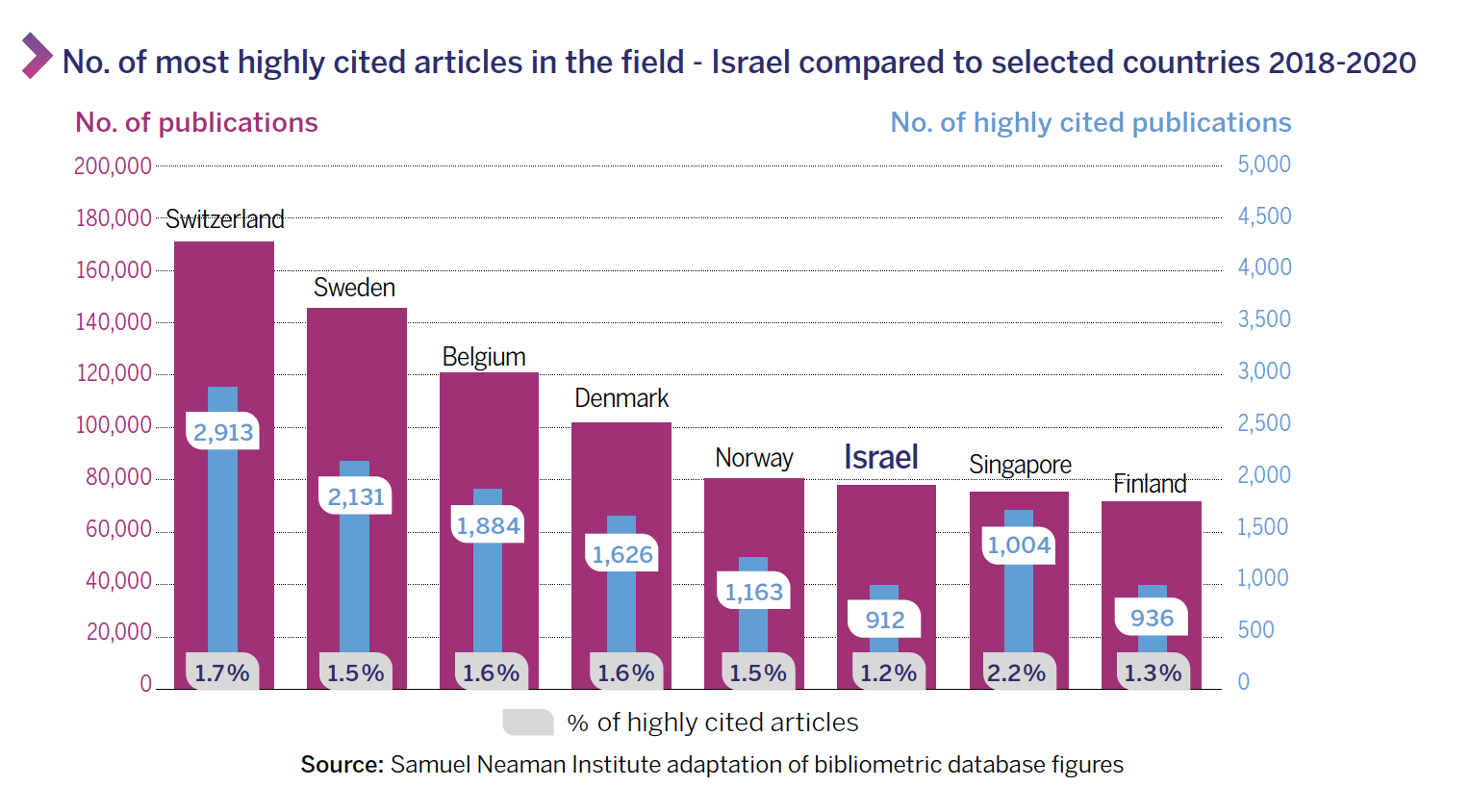

As far as Israeli academia is concerned, it may find Israeli industrial companies, that have in recent years benefitted from the injection of significant capital, to be a source of innovative research questions with high commercialization potential. These collaborations can lead to a growth both in the number of highquality articles emanating from Israel (that is relatively low in relation to the benchmark countries),2See the report published by the Samuel Neaman Institute on R&D outputs in Israel: Scientific Publications – An International Comparison, 2021 (Heb). The benchmark countries are small dad developed economies – Belgium, Denmark, Norway, Singapore, Finland, Sweden, and Switzerland. and in the income of the knowledge commercialization companies in academia. These incomes have suffered an ongoing and significant decline from approx. NIS 1.9 billion in 2012 to just NIS 500 million in 2019. Furthermore, this collaboration may also increase the number of startups that are based on academic knowledge which, although increasing somewhat in recent years, still stands at only several dozen each year.

The importance of collaboration with academia is further reinforced by the fact that it enables brainstorming that ultimately generates the development of novel ideas. A study conducted in 2021 by the Samuel Neaman Institute on the Innovation Authority’s Consortiums Program examined the benefits for each of the parties involved in the joint research. The Consortiums Program creates collaborations between companies from Israeli industry, including startups, and academic research groups for self-development of groundbreaking pre-product technology. The Samuel Neaman Institute study, that was based on questionnaires answered by 250 researchers in academia and industry, revealed that this joint brainstorming is one of the main reasons for entering joint projects.

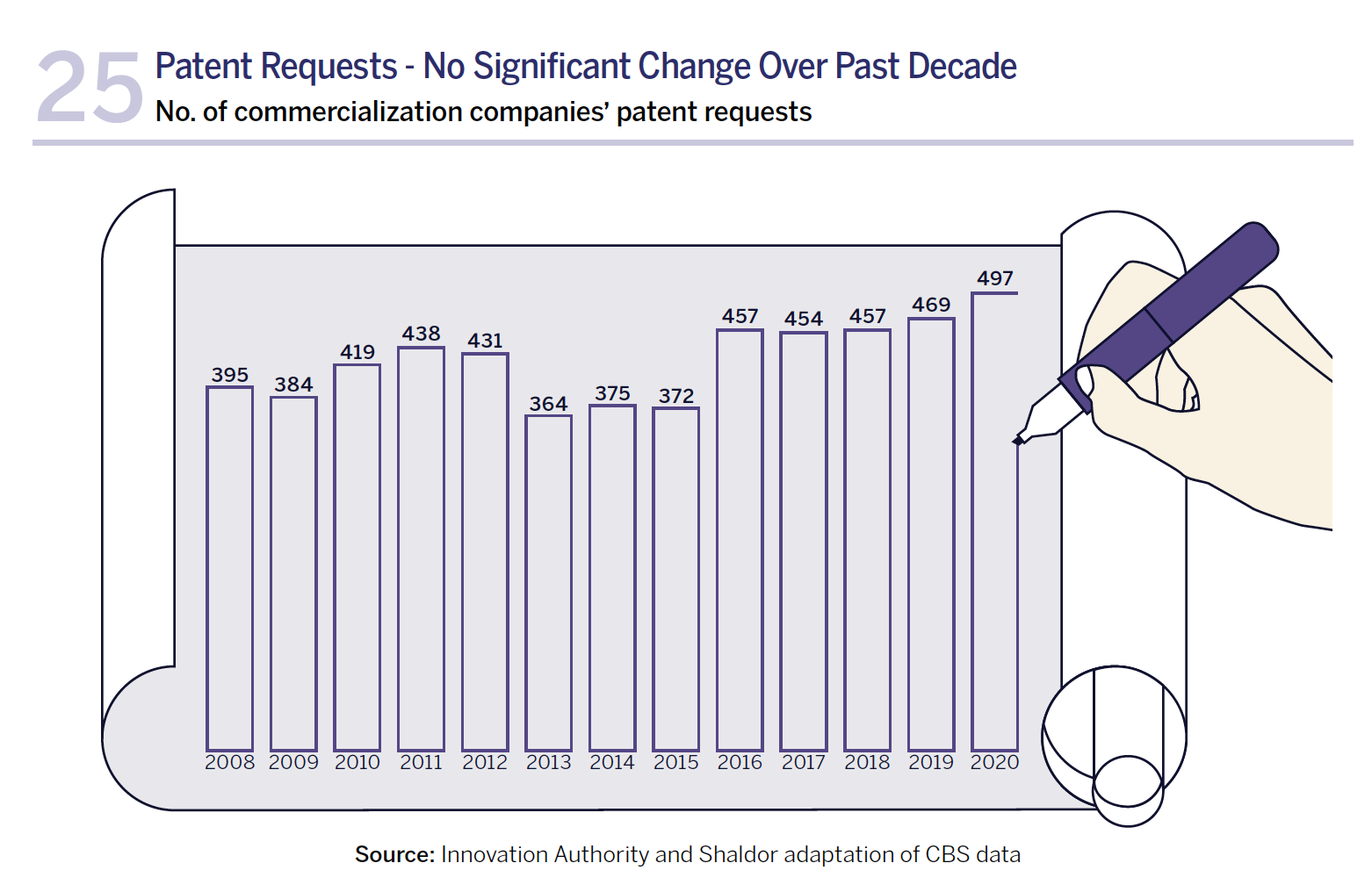

The study also found that the creation of trust and commitment between the two partners is the prime motivation for collaboration, for both academia and industry equally.3Leck, Eran. Gilad, Vered. Getz, Daphne and Tziperfal, Sima (2022). Evaluation of R&D Instruments for Fostering Academia-Industry Collaboration: The Case of the Magnet Consortia. The Samuel Neaman Institute for National Policy Studies (Forthcoming). According to this study, the main outputs of the consortiums’ collaborations are academic articles and patents, indices that have both suffered from stagnation in Israeli academia in recent years. One should note the activity of Tel Aviv University that has shown significant growth via several collaborations with industry. This may stem from the concentration of Israeli high-tech activity in the city.

Another significant warning sign for the quality of the research at the foundation of Israeli high-tech comes from the maturation of the industry expressed in the significant wave of IPOs of Israeli technology companies during the last two years. Studies show that the level of innovation in a company declines by 40 percent following an IPO,4It should be noted that the companies strive to compensate themselves by recruiting new employees, opening startup subsidiaries and, mainly, via mergers and acquisitions. See Bernstein, Shai. “Does going public affect innovation?”, The Journal of Finance 70.4 (2015), 1365-1403. a decline that does not stem from a drop in the scope of R&D activity, which is unchanged, but rather, results from a change in focus of the company’s R&D activity that becomes more conservative and less original, becoming directed towards profit margins. This change in the company’s R&D strategy is primarily expressed in the departure of leading inventors and the decline in productivity of those who remain. In other words, the level of innovation in the wave of current Israeli unicorn companies, and in those that recently conducted an IPO, may be adversely affected, and decline in coming years. To compensate for this, and to maintain the Israeli ecosystem’s growth and level of competitiveness, Israeli technology companies must diversify the sources of their R&D, among others by creating collaborations with Israeli academia. At the same time, effort must be made to ensure that Israeli academia has access to the means necessary to conduct international standard studies.

Strengthening Collaboration Between the Industry and

Academia for a Better High-Tech Future

Several insights arise from the picture presented above: first, collaborations between industry and

academia are based primarily on large and stable companies with a significant cashflow that can afford

long periods of development. In Israel, we see that although there is a fair number of Israeli technology

companies with significant cashflow,525 technology companies traded overseas (90% of them on the NASDAQ) and with a connection to Israel reported a net profit of over USD 10 million in 2020. More than half of them reported profits of over NIS 100 million. these collaborations are overwhelmingly based on large international

companies. Second, in recent years, Israeli academia has generated world-class research, also attracting

the interest of companies with global deployment, although this situation may change due to the relative

decline in research investment in Israeli academia compared to the rest of the world. Third, the current wave

of prosperity experienced by the Israeli high-tech sector, that is expressed in the creation of whole public

technology companies alongside the opening of fewer new startups, may actually lead to a decline in the

quality of R&D conducted in Israel.6The quality of R&D is generally measured according to publication of academic articles and on patents.

Therefore, action should be taken to bolster the research activity in Israeli academia in general and,

specifically, the research collaboration between Israeli academia and Israeli technology companies. The

Innovation Authority operates several programs aimed at creating collaboration between academia and

industry, primarily the Consortiums Program described above. As part of this program, 38 consortiums were

opened between 2010-2021 with the participation of hundreds of large companies, small and medium-sized

companies such as Evogene, Senseera, AccuBeat, and Polygon, as well as dozens of academic institutions

including all the Israeli universities.

Furthermore, because there is generally a significant culture gap between industry and academia, manifested

for example in the different pace of work, objectives, and goals, the Authority operates two programs aimed

at creating collaborations between an individual researcher or small group of researchers and a single

supporting company that identifies commercial potential in the research and is maybe even interested in

adapting it for its own needs. The first of these programs is the Applied Research in Academia Program that

aims to bridge the gap between knowledge created in academia and the needs of the industry, and to create

technological proof of concept (POC) for the preliminary research achievements. The second program is

the Knowledge Commercialization Program that aims to validate the knowledge, adapt it to the company’s

needs, and train the company’s employees, in order to reduce the existing obstacles in commercializing

knowledge from academia.7For more details on these programs, see Appendix.

A good example of the value that a small company can derive from the Authority’s programs supporting

academia and from the collaborations with industry is the Senseera corporation that began operating with

an applied academic project supported by the Authority. As part of the project, an innovative method was

developed in the lab of Prof. Nir Friedman from the Institute of Life Science and the School of Computer

Science and Engineering at the Hebrew University to diagnose a wide range of diseases via a simple blood

test. Using a unique and sensitive technique, the development helps identify dying cells in different body

tissues, thereby enabling to identify a range of different disease situations with a single blood sample,

including various forms of cancer, and heart and liver diseases. Based on this knowledge and with the support

of external investors, the company was established while commercializing the academic knowledge and has

since become a world leader in its field. Today, the company is leading the establishment of a medical fluid

diagnosis consortium consisting of more than 20 different entities: academia, hospitals, biological banks,

and other companies from the fields of sensors and deep genome analysis. The consortium’s goal is to

develop the next generation of disease diagnosis based on a wide range of biological signals, using Artificial

Intelligence.

Connecting Israeli Innovation to the Public and Private Sectors

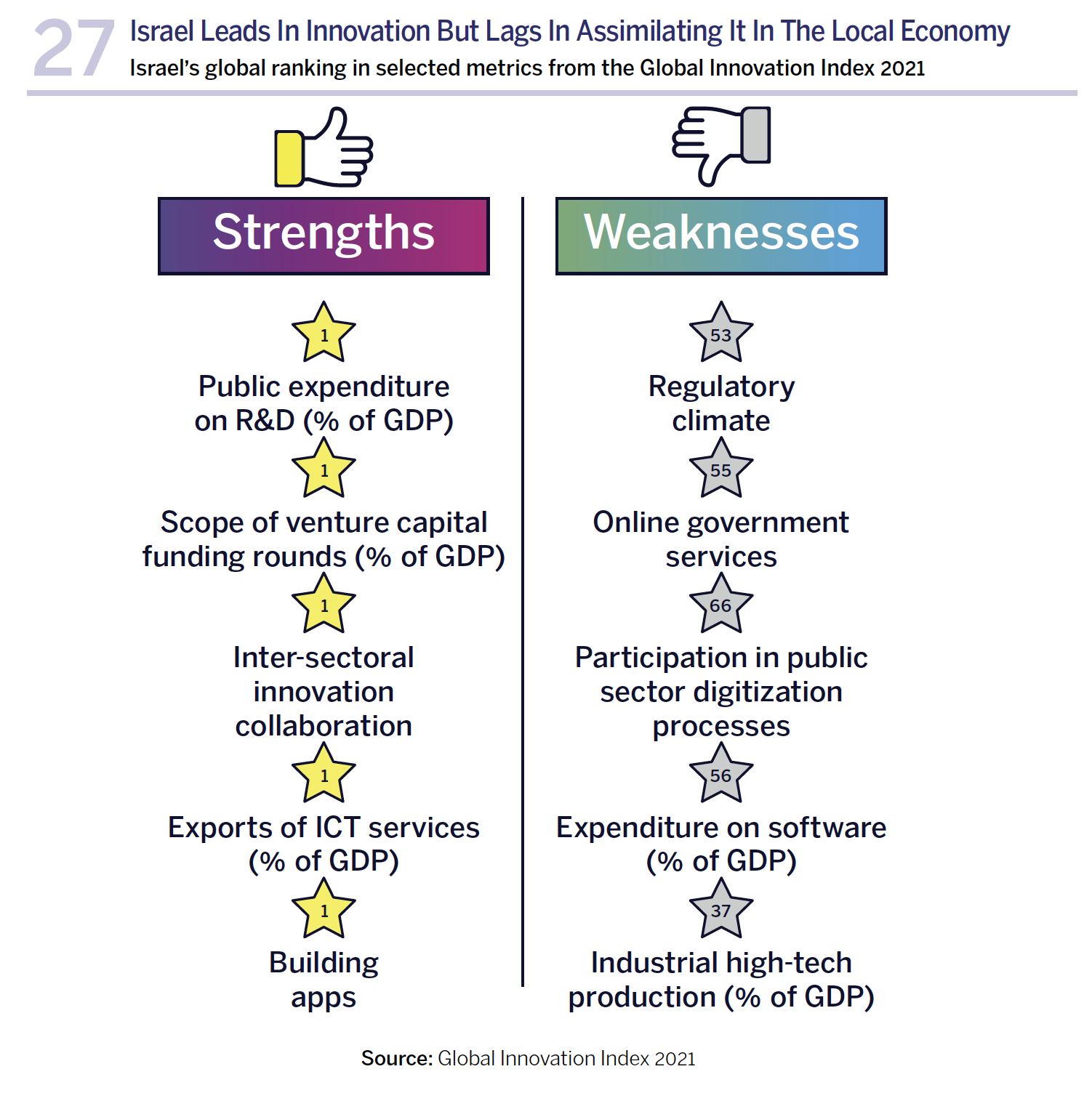

While Israeli technology companies are at the forefront of global innovation, their developments are frequently exported elsewhere and fail to benefit the Israeli economy or its citizens. Furthermore, a disparity exists between Israeli innovation developed in local high-tech companies and multinational development centers, and the level of digitization and technological infrastructures available to these companies. Evidence of this disparity can be seen in Israel’s ranking in various parameters of the Global Innovation Index (GII) for 2021. On the one hand, Israel leads the rankings in different metrics, indicating the breadth and depth of the Israeli high-tech sector, such as public expenditure on R&D, the scope of venture capital funding rounds, export of ICT products, and inter-sectorial collaborations in areas of innovation. In contrast, Israel ranks below average in other metrics related to infrastructures critical for attaining technology advancement, such as a regulatory climate, participation in digitization processes of the public sector, the ratio of expenditure on software out of GDP, and others.8The pace at which advanced

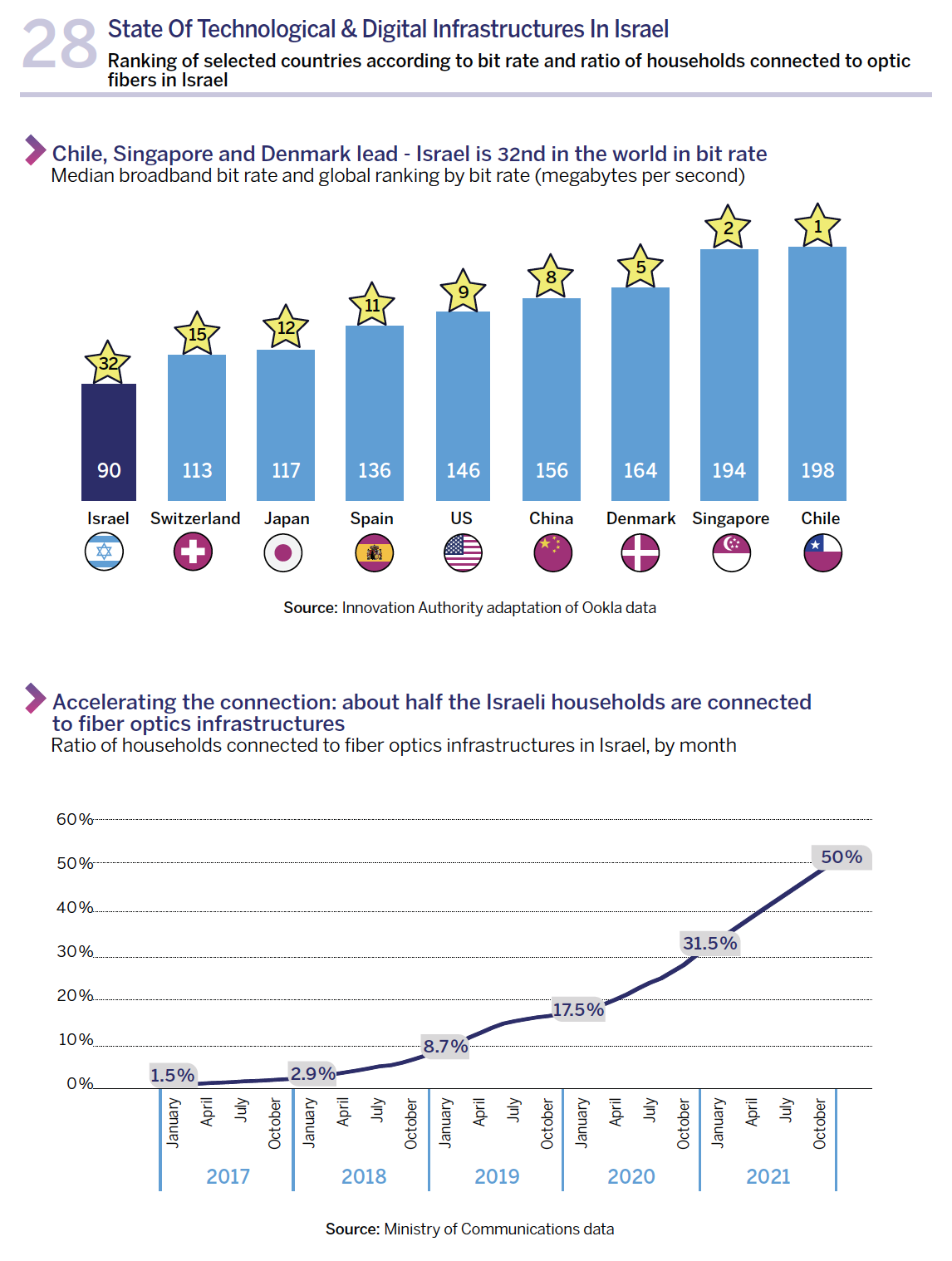

The pace at which advanced communications infrastructures are deployed in Israel – via optic fibers – was accelerated recently and reached 50% of the country’s homes by the end of 2021. This was achieved following a massive investment aimed at closing the existing gap.9Ministry of Communications data. Nevertheless, the available ‘bit rate’ in Israel is still behind that of the world’s leading countries: Israel is ranked 32nd in the world as of February 2022 with a median broadband bit rate of 90.42 MB per second, according to Ookla.10Ookla speed test

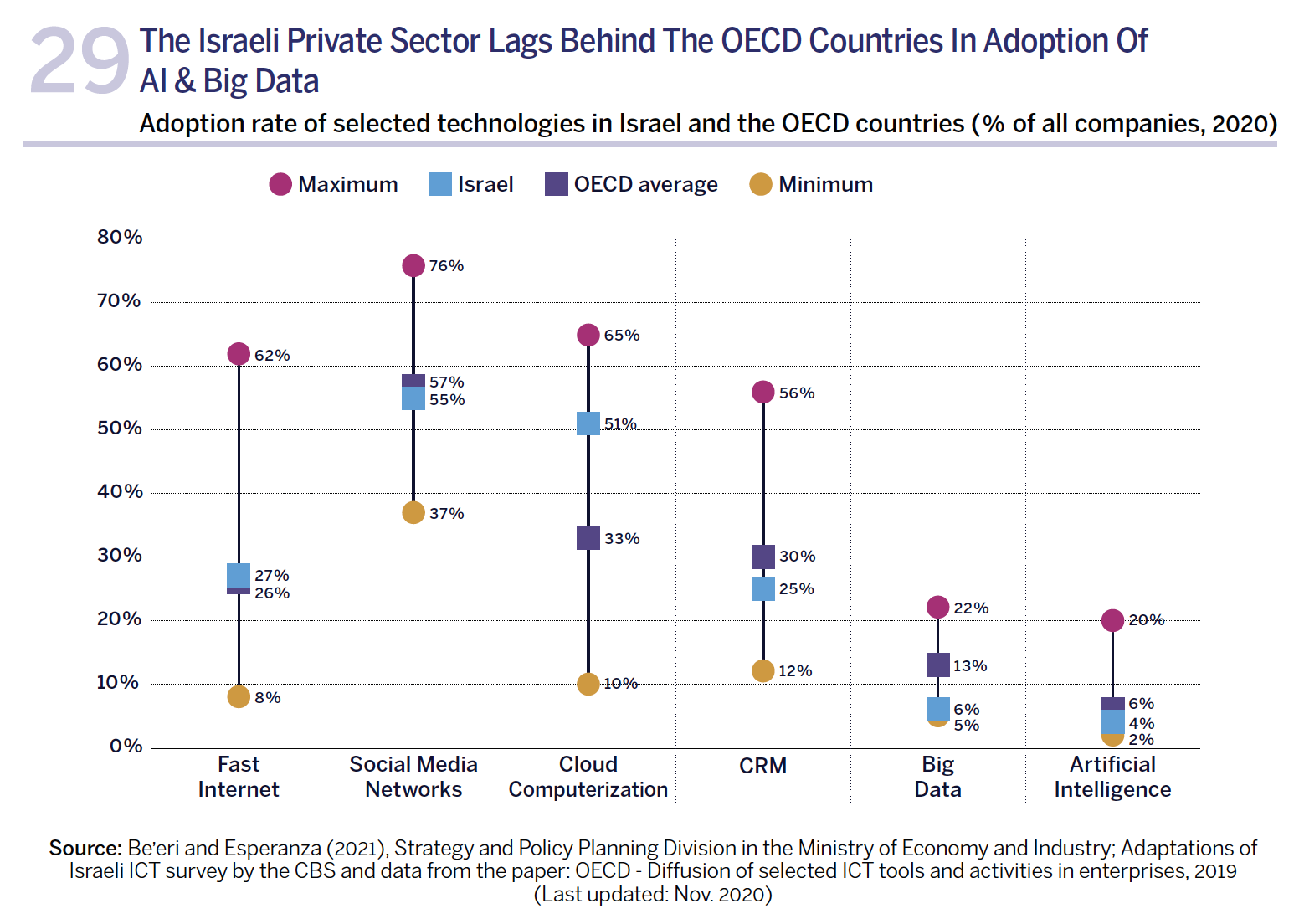

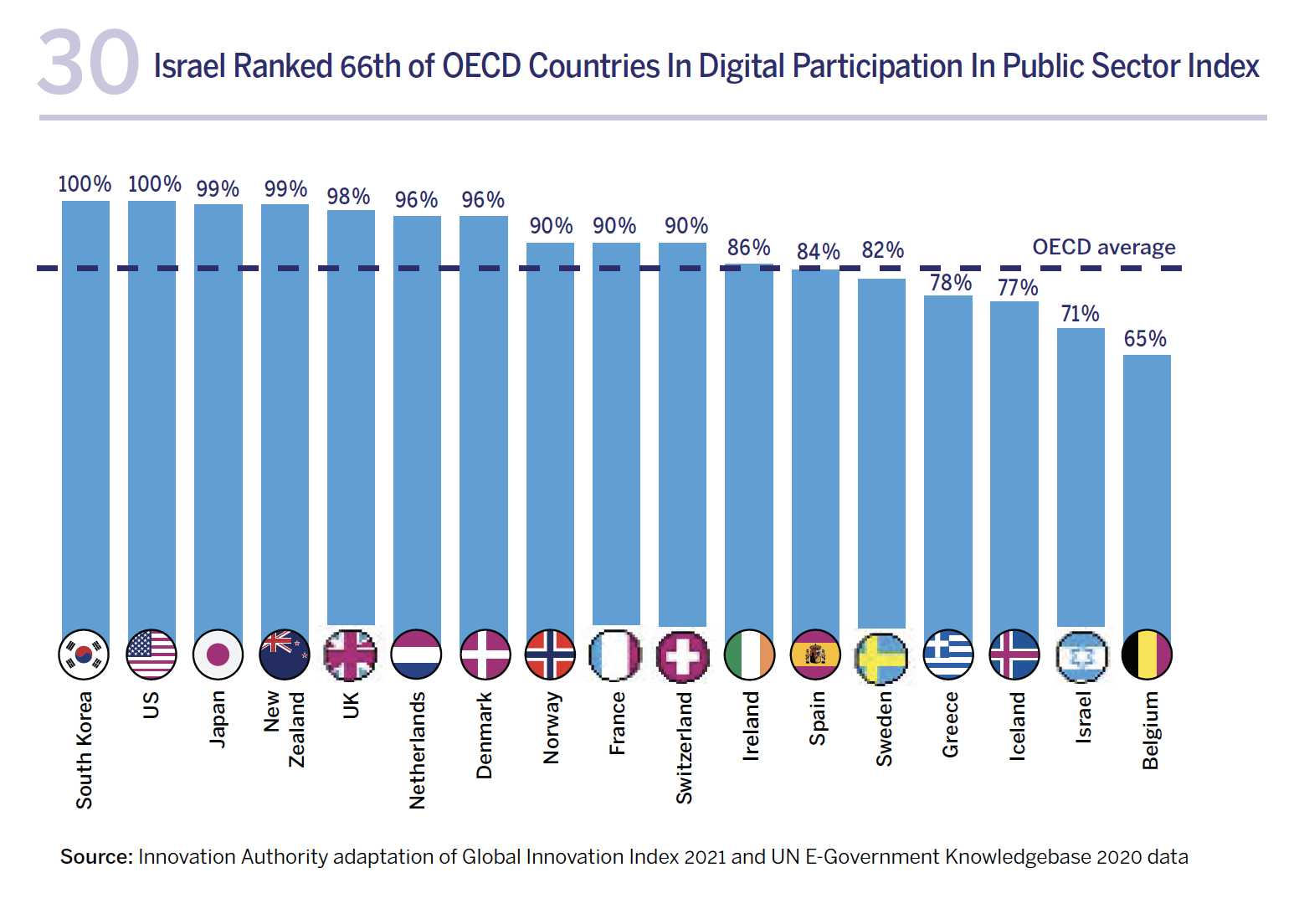

It is unsurprising therefore that the business and public sectors in Israel lag behind the relevant benchmark countries to which Israel compares itself with regard to digitization and technological innovation. OECD data also reveals that the Israeli business sector is below the OECD average in application and use of various technologies such as use of social media networks, cloud computerization, CRM technologies, and big data and Artificial Intelligence technologies. In all these metrics, the Israeli business sector ranks below the average use of the OECD countries. The public sector in Israel also suffers from a similar disparity: according to UN data, Israel is ranked 66th in participation of the public sector in digitization processes.11Public sector digitization processes – UN ranking One of the significant challenges to digitization of the Israeli public sector is a lack of natural language processing tools. In this context, there are two primary obstacles: a lack of economic incentive for the private sector because of the small size of the Israeli market, alongside a lack of databases necessary to train models of natural language processing. The State of Israel is therefore investing 180 million shekels via the National Artificial Intelligence Program to develop natural language processing tools for semitic languages (Hebrew and Arabic).

These disparities have several negative ramifications for Israel:

1. The citizens of the State of Israel do not fully benefit from the fruits of Israeli innovation

Israeli citizens have only limited access to Israeli-made technological innovation which instead benefits the citizens of other countries. For example, the insurance company Lemonade that offers low-cost insurance policies that are priced using AI technologies, does not offer its services in Israel because, the company claims that the database required for the company’s pricing model is not digitally accessible in Israel.12These cutting-edge Israeli inventions are unavailable in Israel – Business – Haaretz.com In other words, in this example, the gap in digitization of government services hinders the assimilation of Israeli innovation and contributes to the high cost of living in places where technology can lower costs. Moreover, companies in the fintech and insurance sectors are subject to regulation, and Israeli startups frequently prefer to adapt their solutions to American or other regulation, rather than to Israeli regulation.

2. Israeli technology companies may transfer activity overseas

Israeli technology companies frequently need an operational environment in which they can conduct initial applications and demonstrations of their technologies during the different development stages. This is especially true for rigorously regulated areas or complex products and services that require infrastructures such as autonomous vehicles, food-tech, and digital health. If Israeli companies do not derive benefit from the pilots and preliminary application in Israel or if the regulatory environment does not enable them to do so, they can be expected to seek these opportunities elsewhere as part of their accelerated growth process. This may weaken the Israeli innovation hub in the medium- and long-terms. In contrast, attractive opportunities for conducting preliminary pilots and applications in Israel can attract important business activity of startups, multinational companies, and pilot beta sites in a diverse range of economic sectors. One example illustrating the potential for the Israeli economy is the National Drone Initiative that was established to advance the use of drones for public benefit. The drones can help reduce congestion on the roads by establishing a national network of aerial routes that can be used, among others, for transporting medicines and medical equipment, or for deliveries in the retail market. The initiative provided all stakeholders – from the operating companies, service providers, technology companies, potential users, and regulators – an opportunity to visualize the future operational environment. The initiative attracted both Israeli and international companies that sought to participate in it despite not having been awarded an Innovation Authority grant, because of the pilot’s unique nature and its contribution to their development. Furthermore, many commercial companies (selling ice-cream, soap, sushi etc.) joined the initiative to test the economic model most appropriate for using drones to deliver their products to the end client.

3. Non-high-tech economic sectors miss out on economic benefit inherent in technological innovation

To take the next step and adapt themselves to the 21st century, all sectors of the economy, including the public sector – from health organizations and ports, via commercial companies, to food companies – must apply innovative technologies. Furthermore, collaboration with Israeli startups via “Open Innovation” processes will expose Israeli companies in all sectors to innovation and, via technology, assist them to establish and reinforce a competitive advantage in the global arena.

To Facilitate, Pilot and Implement: How Government Policy Can Promote Innovation

A collaboration between the public and private sector forces alongside a formulation of government innovation-supportive policy are required to create synergy between Israeli innovation and the daily lives of Israeli citizens, Israeli companies, and the public sector. Such policy will enable the strengthening of the local innovation hub, will ensure its continued global leadership, and will aid expansion of technological innovation’s benefit to further economic sectors.

Thus far, the Authority’s involvement focused primarily on direct financial support to fund high-risk R&D in startups and technology companies. In light of the changes in the required policy and the industry’s maturation, the Innovation Authority’s role has also expanded, and it will serve as a mediator and facilitator in implementing the new policy. The Authority will strive to reinforce the connection between the public sector and the Israeli high-tech industry – both with regard to the public services that Israeli citizens receive, and the public infrastructures used for assimilating innovation (i.e., regulation, physical infrastructures, access to data, and others).

The new generation of solutions that will be implemented by the Innovation Authority and other public sector entities, includes a variety of tools that will transform the government into one that initiates innovation via various projects, into a government that adopts technological innovation as a pilot site and target market, and into a government that facilitates innovation via advanced and flexible regulation. We will now detail how the various new tools are beginning to be executed in projects at different stages of planning and implementation.

The new supportive tools for advancing innovation in Israel:

1. Government Initiating Innovation: Advancing Public and Private Sector Collaborations to Develop Groundbreaking Solutions

Current Situation:

During its initial years of operation, the Innovation Authority (and previously, the Office of the Chief Scientist) espoused the use of supportive tools in R&D without government direction or focus i.e., without indicating specific technological fields or investing in their development and advancement. Underlying this view was the ‘bottom-up’ approach, dependence on the private market (entrepreneurs and investors) to identify and choose technological-business opportunities, and government stimulus in those fields in which a level of innovation can be found at the global forefront.

Required Change:

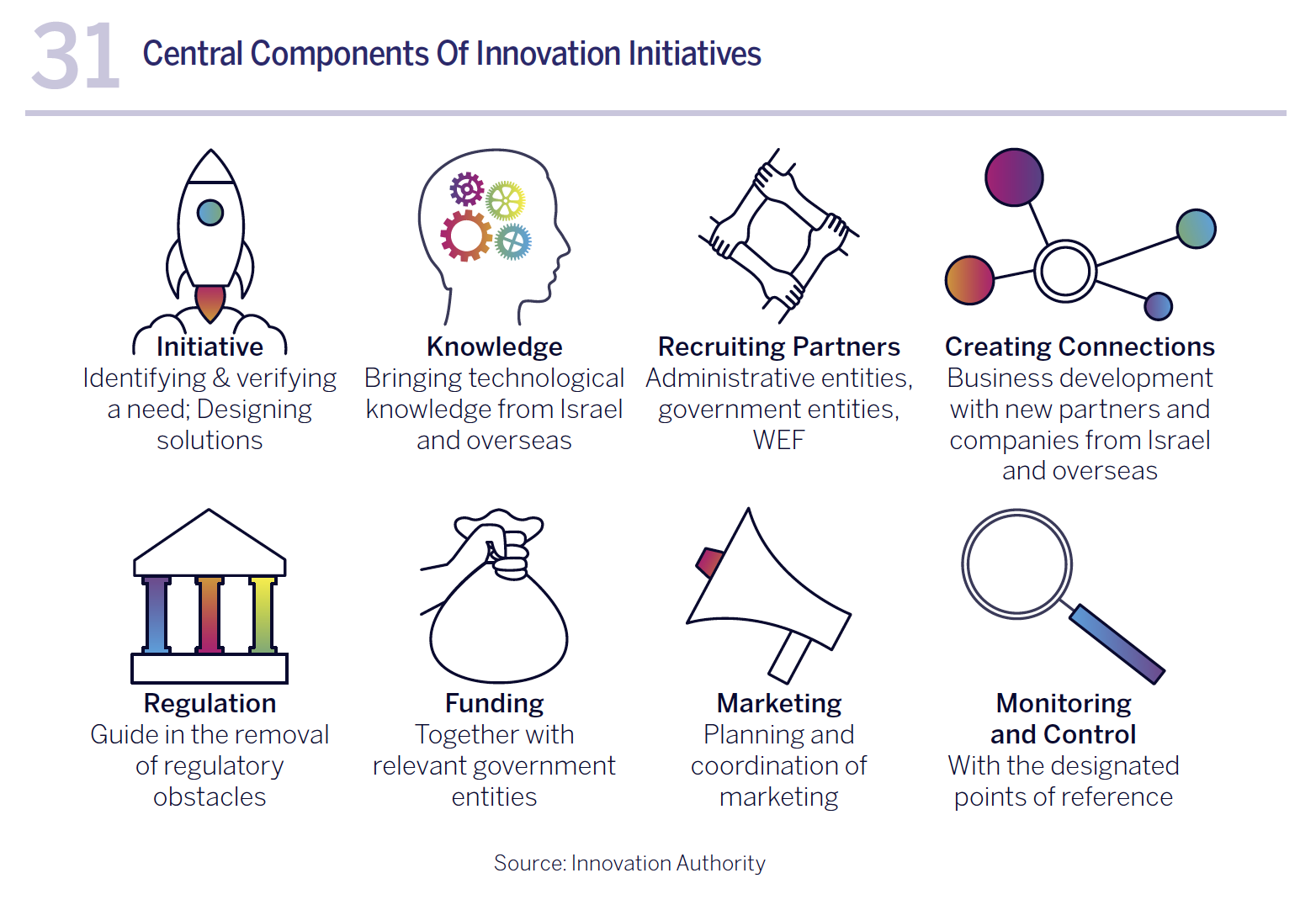

Today, given that Israeli technology companies raise huge sums from the private sector and grow their global activity without any government support, the Innovation Authority focuses on the creation of new supportive tools in places with distinct market failures which, without government support, will prevent Israeli high-tech from continuing to be a world leader. One of the new supportive tools facilitating this is “reality-changing innovative initiatives” – collaborations between the public and private sectors aimed at generating a significant change in a specific and defined area such as public transport or residential construction. These changes will impact the lives of Israeli citizens via assimilation of technology. Innovation initiatives involve government entities, technology companies, regulators, pilot sites for testing technologies, and implementational entities. The inter-sectorial collaborations within the framework of the innovation initiatives will provide unique pilot opportunities while also creating a supportive regulatory and operational framework that will enable the technology companies participating in the initiative to penetrate the market after a successful pilot phase. Furthermore, this support will also allow government and regulators to design future regulatory solutions and to become world leaders in their respective fields. The innovation initiatives will run for 2-4 years and will include identifying a need, gathering knowledge from Israel and overseas, recruiting government and private partners, funding a pilot, and monitoring the results.

The innovation initiatives will focus on areas in which there is a need or a public challenge alongside a technological-commercial advantage for Israel, and in cases where there is a need for regulation or a coordinated government effort to realize the potential. The first innovation initiatives in the fields of smart public transportation and modular construction have already been launched as will be detailed below. During the coming year, the Authority will examine, together with leading government partners, further opportunities to jump-start reality-changing innovation initiatives in fields with an intersection between technological-commercial potential, and Israeli leadership to help in resolving a public challenge.

The First Innovation Initiatives:

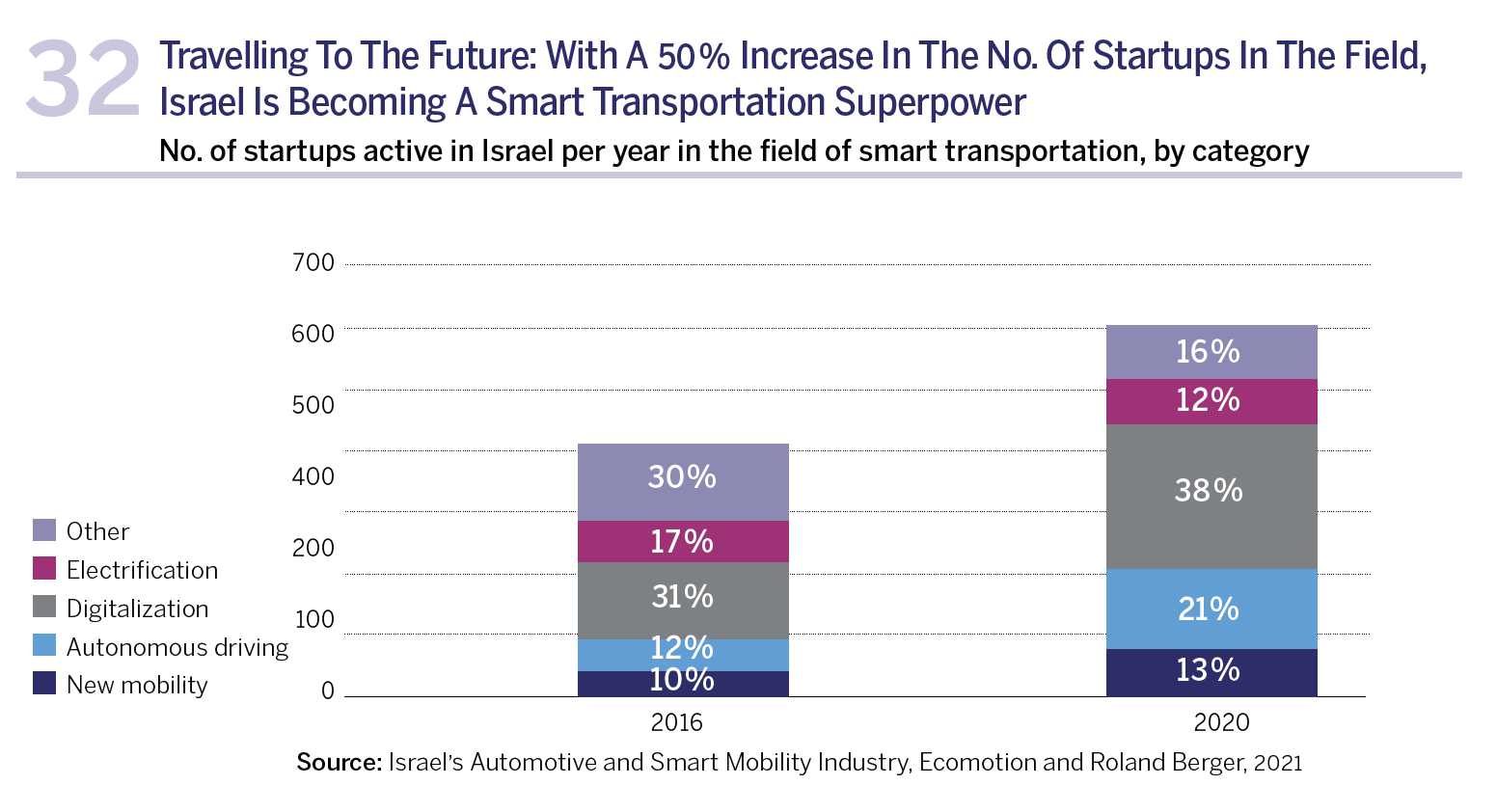

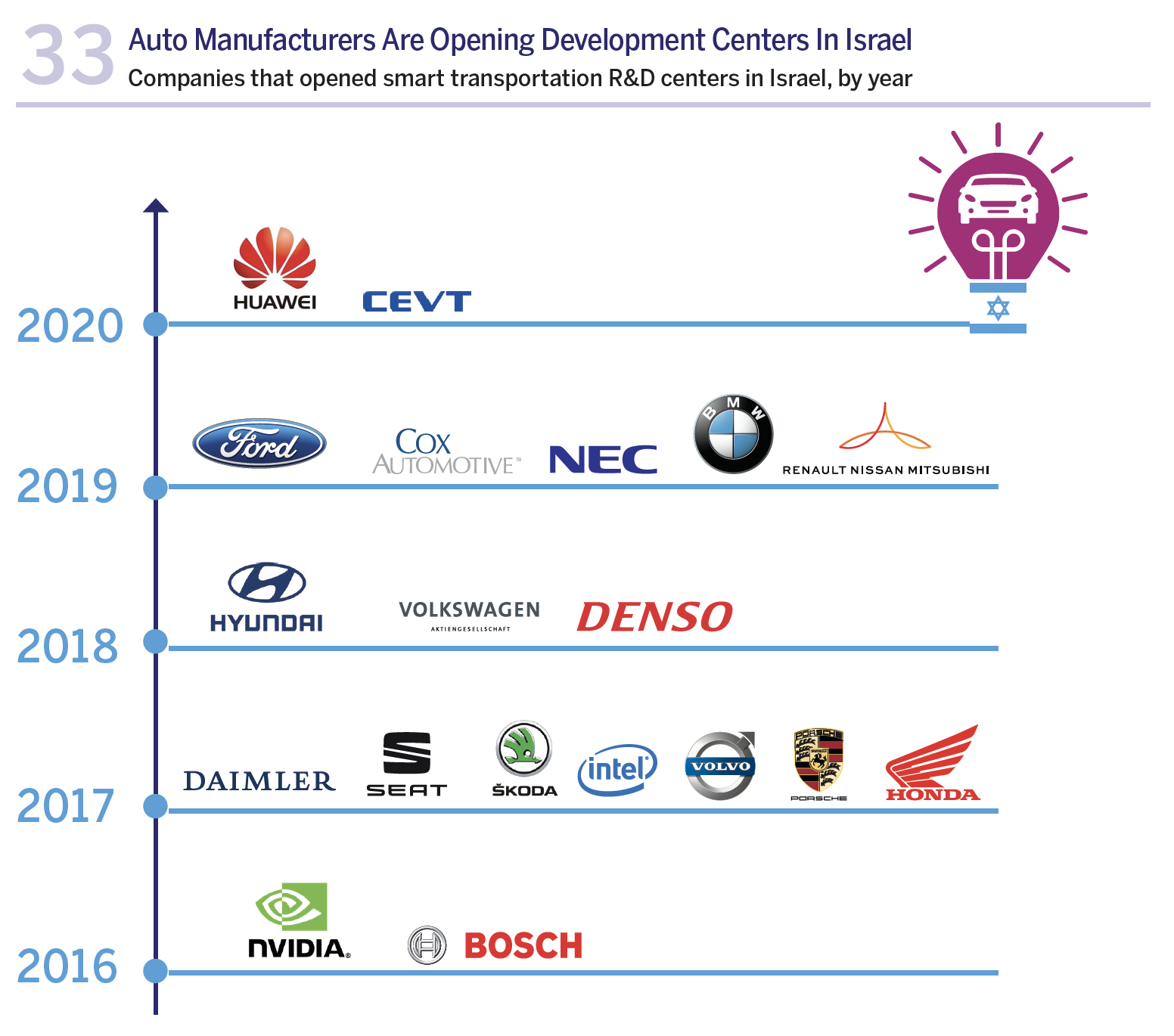

A Joint Initiative to Promote Autonomous Public Transportation in Israel

Although historically Israel has not been a dominant player in the automotive industry, in an era when motor vehicles are becoming smart and driving themselves, Israel has in recent years acquired a leading position in this field. The number of Israeli startups in the field of smart transportation rose from 400 in 2016 to over 600 in 2020. The most significant growth was in the number of startups established in the field of autonomous vehicles with an annual average growth of 26% during this period. Furthermore, since 2008, more than 20 of the world’s largest car manufacturers and their suppliers have opened development centers in Israel, including GM, Honda, Volkswagen, Ford, and others. This field also generates significant business activity with companies raising 1 billion dollars in 2021. Furthermore, one of the largest success stories to come out of Israel in the last decade is the Jerusalem company, Mobileye. The company was established by Prof. Amnon Shashua and Ziv Aviram and developed a technology for advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS), that is also used to develop technologies for autonomous (driverless) vehicles. Mobileye’s IPO in 2014 set the company’s value at more than 5 billion dollars – at the time, the largest IPO by an Israeli company. In 2017, the company was bought by Intel for more than 15 billion dollars in the largest acquisition deal for an Israeli company.

In other words, there is a significant knowledge base for technologies in the auto and transportation field in Israel. At the same time, the startups in this field are contending with challenges that hinder their global growth. According to an EcoMotion survey conducted in 2021, approximately 40% of the startups in this field report that one of their most significant challenges is a lack of access to piloting sites.13Israel’s automotive and smart mobility industry, EcoMotion and Roland Berger, 2021

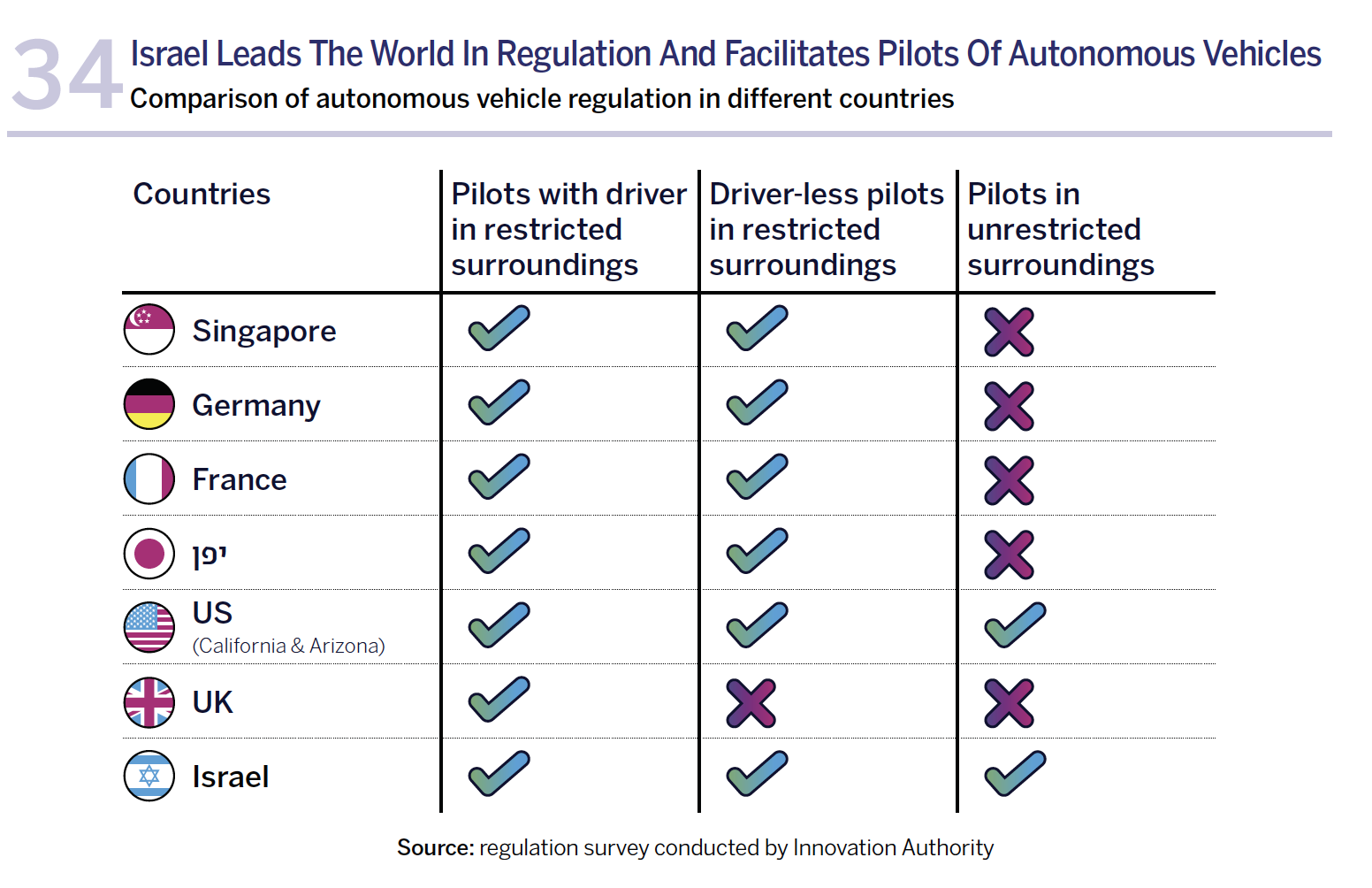

To assist the companies and to transform Israel into a leading global beta site for innovative technologies in the field of autonomous vehicles and to take advantage of the unique knowledgebase created in Israel, an amendment to the Road Transport Order was approved in March 2022. This amendment will enable to conduct more advanced pilots than those permitted today (e.g., operating a driverless autonomous vehicle). Specifically, Israel is especially interested in integrating the market’s existing technologies into the Israeli public transportation system.14Israel’s automotive and smart mobility industry, EcoMotion and Roland Berger, 2021

With the laying of an advanced regulatory infrastructure, the autonomous vehicle can now be harnessed to improving Israel’s public transportation system and to transform Israel into a leading beta site in the field of autonomous public transportation pilots. To this end, a “reality-changing innovation” initiative has been launched to advance autonomous public transportation in Israel. The initiative is being promoted by the Ministry of Transport’s Public Transport Authority, the Innovation Authority, and Ayalon Highways. The expected benefits from the initiative are aimed at one of the largest challenges facing the State of Israel – traffic congestion – by streamlining the public transportation system, improving service and passenger experience, and enhancing safety. Furthermore, the initiative is expected to assist the country and the transportation sector to contend with the problem of manpower and the severe shortage of drivers, via transition to fleets of autonomous buses within the next few years.

How will it work?

During the first stage of the initiative, the companies selected will conduct pilots operating autonomous buses in designated pilots and beta sites, with the goal of achieving technological and regulatory feasibility. In the second stage of the initiative, the companies will operate an autonomous public transportation line on public roads that will steadily increase in scope during the two years of the pilot. The initiative is expected to connect public transportation operators and innovative Israeli and global technology companies that are developing autonomous driving systems, and to increase public exposure to autonomous vehicles and their characteristics – namely, safety, travel experience, and environmental advantages. The initiative will also include an examination of operating models and of their economic efficacy.

Promoting Modular Construction to Increase the Housing Supply in Israel

While Israel has a technological advantage in the field of smart transportation that led to the creation of a joint initiative, the need behind an initiative in another area stems primarily from the demand on the ground – Israel’s housing challenge. The construction industry in Israel creates 55 thousand housing units a year using existing technologies.15Beginning and completion of construction October 2020-September 20201, CBS. This while the future housing demand forecasted for 2040 stands at 70 thousand units a year,16The Strategic Housing Program for 2017-2040, National Economic Council, May 2017. reflecting a need to increase the annual supply of housing units by 30% in less than two decades. One of the ways to contend with the gap in the supply of housing is by extensive assimilation and adoption of advanced technologies to industrialize construction, specifically technology for modular construction. Volumetric modular construction is an innovative construction method in which most of the process is transferred to the factory where complete 3D modules are produced in an “assembly line” method. The modules include the components of the building’s external frame, thermal and acoustic insulation, and even pipeline system, electric devices, bathroom fixtures, flooring, windows, doors, and more. The modules are transported to the construction site where they are assembled into the final building (generally including a reinforced concrete core and base floors). This construction method is expected to shorten the duration of construction by 20%-50% and to increase the industry’s productivity, alongside further advantages of construction quality, site safety, and the environmental impacts of the construction process.17McKinsey & Company, Modular Construction: From projects to products, 2019.

The Ministry of Construction and Housing, together with the Innovation Authority and the National Building Research Institute (NBRI) at the Technion have recently published a call to receive information on constructing buildings using the modular construction method and on establishing factories to manufacture modular units. The goal of this call was to receive information from local and global industry players about the feasibility of widespread adoption of this technology in Israel including the need for supportive regulatory infrastructure and promoting the local manufacturing industry. An NBRI survey conducted among professional entities in the construction industry revealed significant obstacles in the assimilation of the modular construction method in Israel. Among the prominent obstacles found were the high level of coordination required between the various planning and implementation entities during construction, a lack of supportive regulation and standardization, and the need to educate both buyers and renters.18See: Industrialization of Residential Construction Report Via Architectural, Engineering, and Implementational, 3D Modular Units Aspects, 2019

According to the information gathered in the survey, consideration will be given to the possibility of a joint initiative – together with the Ministry of Construction and Housing – to construct residential buildings using modular construction. As part of this initiative, all stakeholders – entrepreneurs, contractors, local manufacturers, and various regulators – will be able to acquire local knowledge of and experience in this method, including practical experience in managing and executing projects of this kind. Furthermore, a coordinated project can help create a unique list of requirements for modular construction in the Building Systems Unit at the Technion that is responsible for approving innovative construction methods. The initiative will provide a tailored regulatory solution and will pave the way to more widespread adoption of this method in Israel. Finally, the project will also help future homebuyers to understand the benefit inherent in the quality of building and living aspects of modular construction.

2. Government Adopting Technological Innovation: The Public Sector as a Playing Field for Piloting Technologies

Current Situation:

As part of the Innovation Authority’s collaborations with a diverse range of public entities, including governmental entities, administrative authorities, government corporations, and local authorities, numerous challenges have been found that influence their ability, especially those of governmental entities, to manage joint work processes with the high-tech industry. Among others, difficulties arise in conducting pilots and acquisition processes with public entities and in assimilating innovative technologies. One of the challenges is the difficulty to characterize the technological solutions required by governmental entities, partly because of limited exposure to market innovations and insufficient familiarity with the existing technologies available in the industry. Even in those cases in which the public sector is partner to characterization and pilot processes of innovative technologies, the acquisition process fails to reach completion and ultimately the technology is not assimilated due to the structure of the public procurement processes that are sometimes cumbersome and overly bureaucratic. Another challenge stems from the fact that in many cases, the high- tech industry fails to approach governmental entities or to adapt its solutions to them. This difficulty is the result of the slow-paced decision-making regarding acquisition and assimilation of technology, and privacy restrictions that prevent governmental entities from sharing the data necessary to adapt the technology to their needs.

Required Change:

To improve the level of cooperation and coordination between the private and public sectors, there is a need to characterize, build, and implement joint work processes between public entities and the high-tech industry. This will enable the parties to familiarize themselves with each other, to reach a common understanding on the challenges, and to complete the acquisition processes on the way to rapid and extensive assimilation of technological innovations. Some of the next generation of Innovation Authority solutions therefore transforms it into an entity that assists and promotes consultation processes with public entities in fields related to technological innovation. The Authority provides support by offering expert technological reviews that help the government entities’ early-stage decision-making process. The Authority also participates, alongside the relevant governmental entity, in funding the adaptation of the technological product to the government needs and its subsequent implementation.

At the same time, the Authority surveys best practices for innovative technology procurement in Israel and overseas, and assists various public partners in accessing and designing similar models. Based on these models, principles can be proposed for synchronizing public and private sector work processes: from the stage of design partnership, via the pilot partnership stage,19See: Innovation partnership procedure to implementation of technology procurement and the assimilation of technology for an ongoing use. These principles are based, among others, on similar processes implemented in the Israeli defense establishment and on the innovation partnership procedure in the EU and UK. This unique procedure enables suppliers to develop technologically innovative products or services while receiving monetary payment throughout the development, and subsequently continuing directly to the stage of acquisition and assimilation without the need for a further tender procedure. These procedures offer a sequential process from the characterization stage, via the pilot stage, through to procurement, with the aim of allowing government entities and technology companies to progress without administrative delays.

3. Government Facilitating Innovation

Regulatory Sandboxes: Adapting Regulation to Test Innovative Technologies

Current Situation:

Regulation plays a key role in promoting or hindering the assimilation of innovation. In many cases where no appropriate regulation exists, a situation may arise whereby no early-stage demonstration of a product or service is conducted in Israel, their production is not conducted in Israel, and they will not be offered for use on the local market. All this while countries worldwide have in recent years developed mechanisms to assist their local companies contend with global competition via technological innovation alongside adaptation of a regulation sandbox for innovative products, services, and business models. As a result, Israel – as an innovation facilitating country – faces increased competition. Required Change: One of the prominent regulatory tools employed in recent years by countries leading the way in assimilation of technological innovation is the “regulatory sandbox”. This method is based on the underlying understanding that innovative technologies develop at a rapid pace which, in general, is faster than the pace at which regulation is created and updated, and that the regulator lacks the necessary technological knowledge to comprehensively regulate the industry. As part of the regulatory sandboxes, governments enable companies and organizations to test innovative products, services, and business models without complying with all the existing regulatory rules and while significantly reducing the regulatory uncertainty. This way, companies can test products and services in a facilitating and safe environment without violating existing regulatory constraints. Regulatory sandboxes also include additional tools such as regulatory signposting and nonenforcement letters in which the regulator expresses his intent to forego enforcement of certain regulatory clauses in order to facilitate the activity of a company offering innovative products or services.

Regulatory sandboxes also have significant advantages for the regulators themselves, enabling them to learn and become familiar with the industry and its needs by establishing an independent connection with the industry. In this way, they encourage regulators to collaborate with the industry by creating defense mechanisms for consumers when adopting innovative products. Furthermore, these regulatory sandboxes help regulars to identify a need for regulatory reforms and for the creation of information-based regulation.

One of the prominent fields in which countries operate regulatory sandboxes today is fintech.20See: The Map of Regulatory Sandboxes In 2020, there were approximately 70 regulatory sandboxes operating worldwide. This approach has also gained momentum in recent years in additional fields such as transportation, health, and climate. For example, in 2018, Japan announced a general regulatory sandbox, not limited to a specific pilot, that covers the fields of financial services, health, and transportation.21For information on the regulatory sandbox program in Japan, see

Regulatory sandboxes are expected to constitute a critical layer of an innovative regulatory environment that will support the financial and taxation tools and will encourage the penetration of innovative products and services into the Israeli market in a way that aids market acceleration and its increased growth. An advanced and innovative regulatory environment in which it is possible to experiment in research, development, assimilation, and marketing of innovative technologies constitutes a significant magnet for Israeli and foreign high-tech companies.

An Example of a Regulatory Sandbox: Testing Autonomous Vehicles

The introduction of autonomous vehicles into the public domain significantly increases the potential to change the future of Israeli transportation and accelerates the development of local industry, economic growth, and the efficiency of the transportation sector. Furthermore, it can increase the safety of passengers and pedestrians and reduce traffic accidents. At the same time, the development processes of autonomous vehicles pose complex technological and regulatory challenges. The State of Israel, at the forefront of development in the field of advanced technological systems for autonomous vehicles, is therefore striving to remove the various obstacles in order to advance this trend.

Tests in driving autonomous vehicles have been conducted throughout Israel since 2018, including the independent driving system driving the vehicle, but these include a backup driver responsible for taking control of the vehicle in case of emergency. Furthermore, there are no passengers in the vehicle during the tests and it is not used for commercial purposes. These tests are conducted according to a specific permit provided by the National Traffic Supervisor who is qualified to exempt those conducting test on a vehicle from the obligations of drivers in regular vehicles, such as the driver’s obligation to hold the steering wheel.22According to Regulation 16a of the Road Transport Order

A precedential law, composed by the Ministry of Transport and Road Safety together with the Ministry of Justice and with the professional support of the Innovation Authority, came into effect in March of this year. This law was the result of a 2017 government resolution about the creation of a national smart transportation program. The legislation will transform Israel into an autonomous vehicles’ beta site at the highest levels of autonomous driving so that, for example, the pilots can evaluate car safety without the presence of a driver. Among the leading countries alongside Israel in this field are California and Arizona in the US and other countries in Europe – Germany and France – and in East Asia – Japan and Singapore. Israel enables to check passenger and commercial service solutions with autonomous vehicles, a reality that is expected to transform Israel into an attractive global focal point of piloting and assimilating this technology. The uniqueness of Israel’s sandbox is the possibility of commercial operation of a driverless autonomous vehicle anywhere and without restrictive constraints. This possibility is also recognized as Level 5 Autonomy although Level 5 autonomous vehicles have not yet been fully developed. In practice therefore, the State of Israel has prepared a regulatory infrastructure for a future technology and will be able to progress to pilots of fully autonomous vehicles when this technology becomes available.