Guaranteeing the Israeli economy’s continued prosperity and the leading global position of its high-tech industry depends on several key factors. One of these is a state policy that supports the creation of infrastructures necessary to develop innovative technologies and train the next generation of high-tech employees. At the same time, significant changes in the government’s policy and regulatory perception will aid Israel’s recovery from its largest ever economic crisis by implementing Blue & White technology solutions.

Like most countries, Israel’s economy has been dramatically impacted by the Covid crisis and its ramifications. However, when closely examining Covid’s influence on the different sectors of the local economy, it is clear that the crisis has only emphasized existing gaps between high-tech and the economy in general. This polarity is reflected in the way in which the high-tech sector was affected by and contended with the crisis compared to the other hard-hit sectors which suffered from reduced demand and continued to suffer from high levels of unemployment relative to the pre-Covid period.

As we have shown, high-tech was adversely affected by the crisis and high-tech employees, primarily those earning less than NIS 15,000, did lose their jobs or were sent on unpaid leave during the first lockdown period, however the reaction was swift. The flexibility that characterizes the high-tech sector was reflected in the quick drop in salaries and almost no use was made of the option to send employees on unpaid leave. CBS surveys conducted in May-June 2020 reveal that on average, 22% of high-tech employers instituted salary cuts while in the other sectors of the economy, only 10% of employers on average adopted this measure.Results of the “State of Businesses during the Covid Virus Outbreak” survey, waves 4, 5, 6. Furthermore, CBS surveys conducted at the beginning of the Covid crisis in March-April 2020 reveal that only 2.6% of high-tech employers sent their employees on unpaid leave compared to 11% of employers in the economy as a whole.Results of the “State of Businesses during the Covid Virus Outbreak” survey, waves 2 and 3. Evidence of this can be seen in the fact that at the height of the first lockdown period, the overall ratio of unemployment benefits’ recipients was double that of the high-tech sector, 28% compared to only 14% in high-tech.Innovation Authority adaptation of NII data. The Covid crisis continued to impact the other different sectors of the economy during subsequent lockdown periods more than the high-tech sector although the disparities in these impacts gradually declined.

In summary, Covid caused a rise in the level of inequality in Israel. The adverse impact of Covid was concentrated in those sectors of the economy typified by low productivity, with the younger and less-qualified employees generally being the most affected in each sector.See for example, Chapter 1 of the Bank of Israel Report, 2020. Another prominent difference between high-tech and the other sectors relates to the move to working from home. High-tech succeeded in making the transition from work at the office to working at home smoothly and relatively quickly. In organizations in which numerous teams of employees are scattered throughout the world and most of the work is performed via computer, the ongoing disruption to work was relatively small. In contrast, in other sectors in both the public and private sectors, organizations encountered greater difficulty in making the transition from office to home.

There are various reasons for these difficulties: first, there are some sectors of the economy in which the workplace itself is the focus of work, therefore precluding a move to the home. A CBS survey conducted in January 2021 revealed that most employees who lacked the option of working from home worked in construction and retail sectors – work that is based at a specific physical location.Results of the “State of Businesses during the Covid Virus Outbreak” survey, wave 10. Second, it seems that, apart from high-tech, few of the other sectors which had the option to adopt digital services and make the move to working from home, such as building an online store, indeed took this step. Non-high-tech sectors were thus quick to return to working in the office between lockdowns. A CBS survey conducted in June 2020, immediately after the first lockdown, revealed that the ratio of high-tech employees working from home remained high at 37%, while this figure dropped to just 3% in the other sectors of the economy.Results of the “State of Businesses during the Covid Virus Outbreak” survey, wave 6. A more detailed discussion of the transition to a hybrid work model that combines work from the office and home following Covid is presented below.

As the economy gradually reopens and begins its revival, the question arises as to how the hightech sector and the introduction of innovative solutions can help economic recovery and what the other sectors of the economy can learn about how to contend with global economic crises. Furthermore, in this chapter we will examine how the implementation of Israeli technological solutions can be utilized to improve services provided to the citizens and to streamline the Israeli public sector.

High-Tech’s Large Contribution to the Economy – How can we Ensure its Continued Growth?

Public expenditure in Israel increased significantly during the Covid crisis as the result of the support provided to affected sectors of the population, aid given to ensure continued business activity in an economy that was partially closed, and the support provided to the health system and to the formation of the mechanism required to deliver the vaccine. Now, with the beginnings of economic recovery and return to routine, the need to reexamine public spending has become more acute, especially in light of a sharp increase in the Debt-GDP Ratio and in the development of broad growth engines that will enable its rehabilitation. This need emphasizes high-tech’s importance to Israeli economic growth and the central role it will play in its recovery following the Covid crisis. It is important therefore to ensure the preservation of Israeli high-tech resilience and its global competitiveness.

The high-tech industry’s important role in the Israeli economy is one of the factors in the moderate adverse economic impact of the Covid crisis in Israel compared to other developed countries.

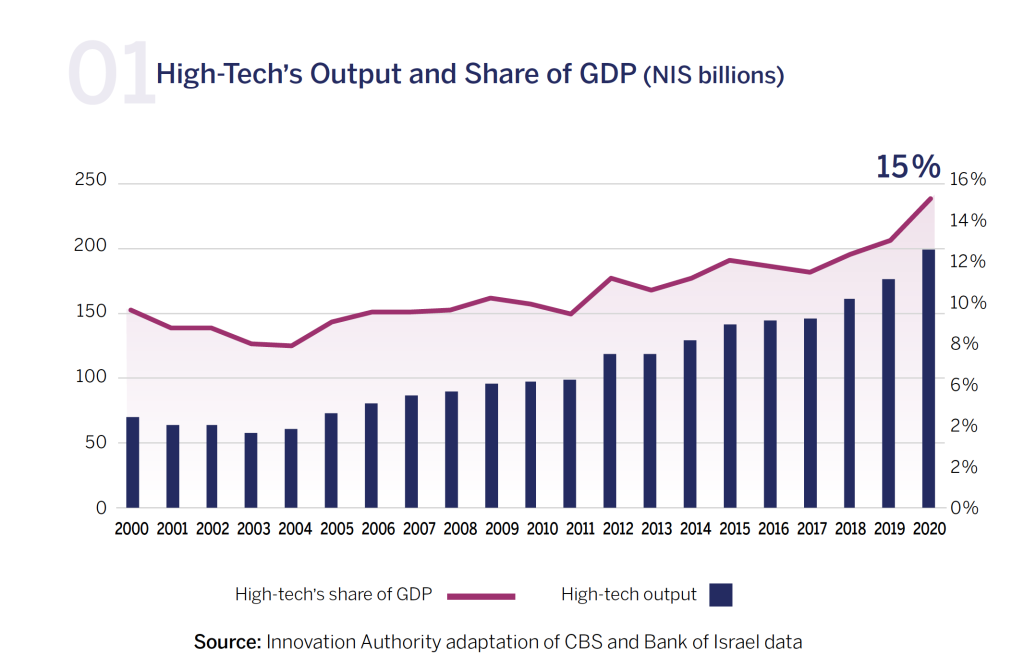

The high-tech industry has formed itself in recent decades as one of extreme importance to the Israeli economy. High-tech’s share of GDP has increased from 10% in the year 2000 to 15% in 2020 with most of the growth taking place in the last 3 years. Among others, a recent Bank of Israel report stated that the Israeli high-tech industry’s important role in the local economy is one of the factors in the moderate adverse economic impact of the Covid crisis in Israel compared to other developed countries.See Chapter 2 of Bank of Israel Report 2020, p. 25. In general, the high-tech industry’s contribution to a variety of economic indices is larger than its relative share of the economy, among others, in exports, tax payments and other indices. High-tech’s importance to the Israeli economy cannot be overestimated. As presented in previous chapters, the hightech industry’s share of all Israeli exports stood at 43% in 2020 (or 45% excluding diamond exports). Both its share of exports and absolute size are increasing consistently. Examination of the public high-tech companies reveals further evidence of the growing significance of the high-tech industry to the local economy. According to an Innovation Authority study, if the Israeli high-tech companies traded on overseas stock exchanges would join the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange, the total value of the companies comprising the Tel Aviv-35 Index would jump by more than 70%, and the weight of high-tech companies in the index would stand at 70% compared to 40% today.Israeli high-tech companies were defined broadly as those with a connection to Israel. Among the companies on the list: Palo Alto Networks, Wix, Check Point, SolarEdge, Playtika, Fiverr, Compass, Varonis Systems, Cyberark, Lemonade, Coursera, Kornit Digital, Jfrog, and Verint. The value of the companies was calculated as of 25.4.2021 and in shekel terms.

As far as their contribution to tax payments is concerned, we have shown that although the level of high-tech employees in 2018 was less than 9%, they accounted for approx. 25% of all income tax payments. In other words, high-tech employees are responsible for income tax payments that are almost 3 times higher than their relative share of the labor market. The number of high-tech employees is expected to continue growing in coming years, partly because one in every four students in Israel today is studying a science or technology subjects, and a marked proportion of them are expected to find work in the high-tech industry.

The central role of the high-tech industry in the Israeli economy together with the importance of rehabilitating the economy and creating additional revenue from taxation and other sources to reduce the Israeli debt-GDP ratio, have emphasized the need to ensure that the necessary efforts are being made to safeguard the industry’s global standing and competitiveness. These efforts must focus on all relevant fronts including the continued expansion of quality personnel training in world-class academic institutions, adapting regulation to support implementation of future generation technologies in fields such as drones and autonomous vehicles, and creating competitive taxation laws that will encourage Israeli and multinational companies to continue employing in Israel and to increase the number of their employees despite the high costs involved.

Furthermore, the government as a whole and specifically, the Innovation Authority, must continue identifying future fields and directions of the technology world requiring heavy investment for the creation of national research infrastructures and long-term planning. Examples of these fields are nano-technology – a field in which two national programs have been createdSee a survey conducted by the Knesset Research and Information Center, 2017: “Nanotechnology in Israel – Information and Figures”. – and the field of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in which Israel lagged behind other countries in presenting a national program. According to a report issued by the Artificial Intelligence and Data Science Committee there is “a worrying gap between Israel’s leading position in R&D and trade, and its low ranking in the infrastructures required and in government policies, which casts doubts on Israel’s progress and on its ability to reinforce its standing in this field”.See Artificial Intelligence and Data Science Committee Report, December 2020. The committee presented a multi-year work plan with a budget of over NIS 5 billion. The first segment of this budget (NIS 500 million) was approved for investing in the creation of super-computerization infrastructure, generic R&D with an emphasis on Natural Language Processing (NLP), and the training of manpower and procurement of advanced equipment in academia. A further field is that of Bio-Convergence (multidisciplinary research that combines engineering and biology – more details are presented below) in which the Authority is investing considerable resources.

Another central issue is how to expand the circle of high-tech employees. Although the absolute number of employees in high-tech has risen for more than two decades, their ratio of the total number of employees in Israel has not exceeded 10%. As we have shown, the ratio of high-tech employees does not include diverse populations that could benefit from its advantages. On average, high-tech employees earn more than double the average salary and in turn generate high tax revenues for the state economy. Nevertheless, there are significant hurdles to integrating into the core technology jobs that require relevant academic and professional training. The potential growth and expansion of high-tech is therefore limited to the number of university graduates in science and technology degrees and those serving in IDF technology units.

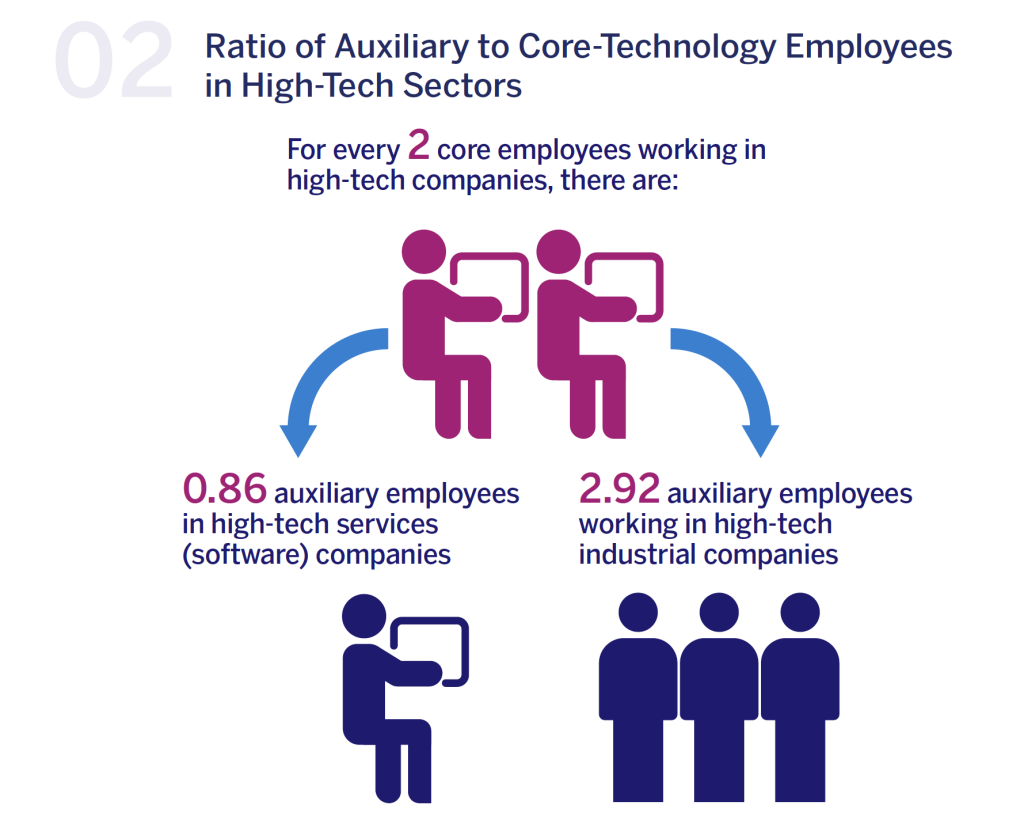

Another way to expand the circle of high-tech employment relates to increasing the number of employees in non-core technology jobs such as sales, marketing, human resource management etc. Among those suitable for these positions are employees in sectors that have suffered significantly and in which employment has become uncertain during the Covid crisis such as tourism, aviation, and retail. As discussed in Chapter 1, the maturation of the Israeli high-tech industry is reflected in the growth of Israeli companies which have become “complete” and independent companies that are not sold off in the short term and which employ many employees in a variety of jobs. These companies also offer potential employment in non-core technology jobs, thus explaining the importance of supporting the creation of complete companies that will fully utilize the diverse range of available employees in Israel.

It is important to clarify that high-tech is not a uniform field and that the creation of “complete” companies focusing on software differs from high-tech companies that produce tangible products. The latter category of companies, where the production processes themselves generally constitute a complex technological development, requires broader government support, including in areas of regulation and taxation. The greater support for companies manufacturing a tangible product is coupled with larger potential for the economy in general. First, as mentioned in Chapter 1, these companies employ three times the number of employees in non-core technology jobs out of the total number of employees compared to software companies. Second, establishing a sophisticated production plant, usually after recognizing the importance of proximity of the development and production systems, constitutes a local mainstay that connects the company to Israel and makes it difficult to close or downscale local activity, even if the company is bought by an international corporation. Third, these worlds include an accompanying industry of subcontractors, some of which are advanced and significant industries in themselves. A growth in the local high-tech production industry is expected to support growth in the subcontractors’ industry and to expand the scope of hightech influence.

The efforts to preserve hightech’s standing must focus on training, identifying future technological directions, and advancing innovative regulation.

In summary, there are several ways to widen the circle of high-tech employees, from increasing the potential manpower suited to core professions by encouraging populations under-represented in high-tech, expanding high-tech’s borders to additional worlds of content such as biology, identification of and support for future technology waves, and creating a system of incentives aimed at supporting the growth of “complete” companies.

Online Commerce and Remote Medicine: Business Opportunities Created by the Covid Crisis

The Covid crisis has impacted many sectors of the economy which were forced to suspend or severely downscale activity, notably tourism and aviation, due to global restrictions of movement. However, the crisis also created new opportunities for the Israeli economy and strengthened pre-existing trends related to digital transformation and a move to online commerce. A CBS survey from October 2020 revealed that 45% of Israeli businesses lack any digital interface and another 30% made no changes or improvements to their digital interface during the crisis.Results of the “State of Businesses during the Covid Virus Outbreak” survey, wave 9. At the same time, during the year of the Covid crisis, many businesses in Israel had their first experience of online trade and deliveries and, due to Covid-related constraints, took the leap to the digital age. With the return to normal routine, these businesses now have an opportunity to continue in this direction and expand their portfolio of products and services and their geographical deployment.

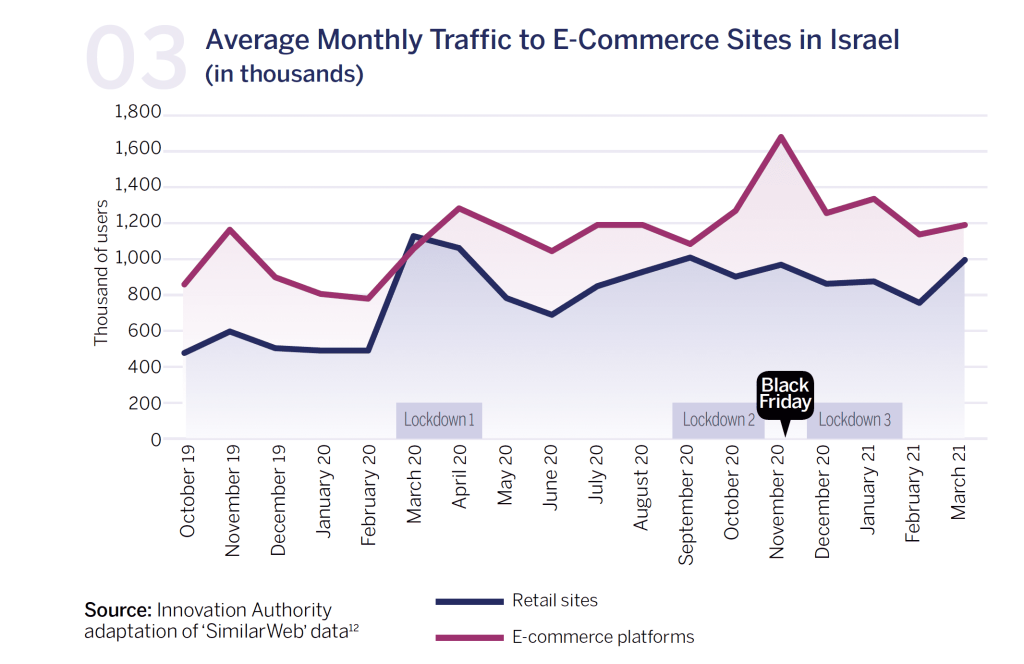

Lockdown restrictions impacted the Israeli population which increased its use of online commerce e.g., the elderly population, which for the first time gained practical experience in online shopping. This influence did not end after lockdown, however. Findings’ analysis of the Israeli company SimilarWeb which monitors website traffic, shows that there has been a rise in the number of Israelis visiting prominent e-commerce sites throughout the Covid period, with an emphasis on retails sites, especially during the first and subsequent lockdowns.

Among the sites on which user traffic increased are online supermarkets, electric products, housewares, fashion, and pharma. Of special interest is the new point of equilibrium that has been created with the number of those using online commerce sites now higher than before the Covid crisis. In other words, Israelis who had their first experience of online shopping during the Covid crisis or who increased their use of these sites during lockdown, continued using the e-commerce sites after regular retail, street shop and shopping malls reopened. The rise in online traffic grew approximately 80% during the long months of Covid compared to the preceding period and about 40% on e-commerce platforms.

The State of Israel must utilize the opportunity that this accelerated trend offers to increase business productivity and support business opportunities made available by online commerce, including opening Israeli business that have focused until now on the local market to international trade. The growth of Israeli businesses is essential for economic recovery, the creation of new jobs, and for improving the services that Israeli consumers enjoy. To enable this, steps must be taken to ensure that businesses apply the different e-commerce technologies and that the local logistical services are efficient because, as mentioned by the Innovation Authority, these are characterized by significant advantages of scale.See the Recommendations Chapter in the Innovation Authority Report “Personal Import as a Tool for Advancing Competition”.

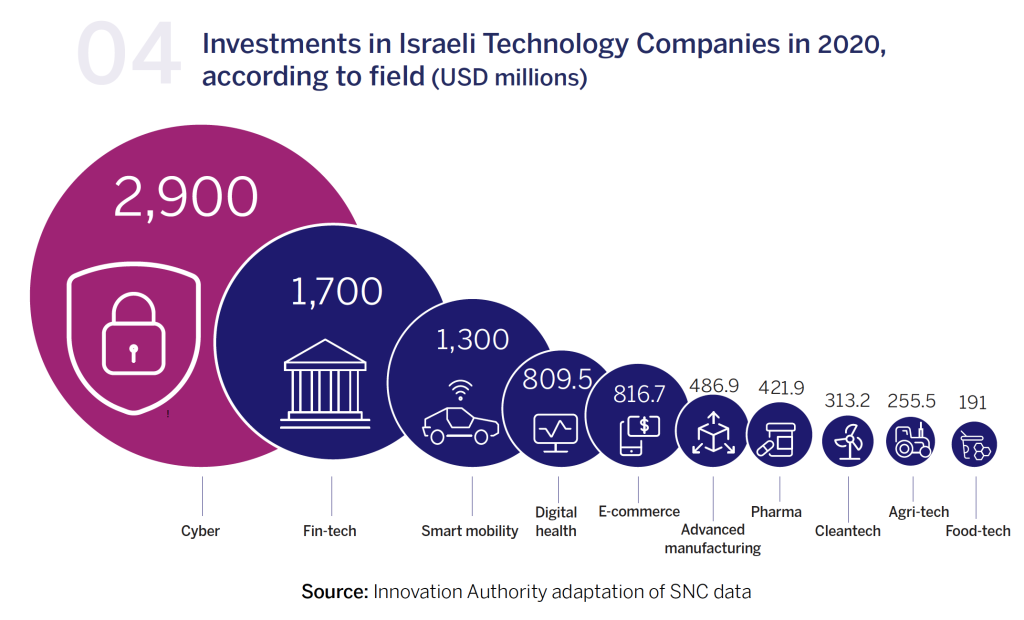

New opportunities have also been created for Israeli technology companies developing and exporting solutions in fields with increased demand, and which produce the technological infrastructure for digital transformation. The changes in global demand have naturally also benefitted the Israeli technology companies that are developing solutions in areas with increased need. One such example from the past year was the clearer need for and resultant removal of hurdles related to implementation of technologies in the field of digital health, including technologies providing remote medical services (tele-medicine). Opportunities also arose for companies that develop technologies used as infrastructure for telecommuting. Furthermore, to enable global companies to implement rapid digital transformation during the Covid crisis and to support demand for e-commerce platforms, technological developments were needed that enable clearing, secure trading infrastructures etc. Consequently, the demand for cyber and fin-tech technologies – two fields that we have shown to be the leaders in raising capital for high-tech – remained high.

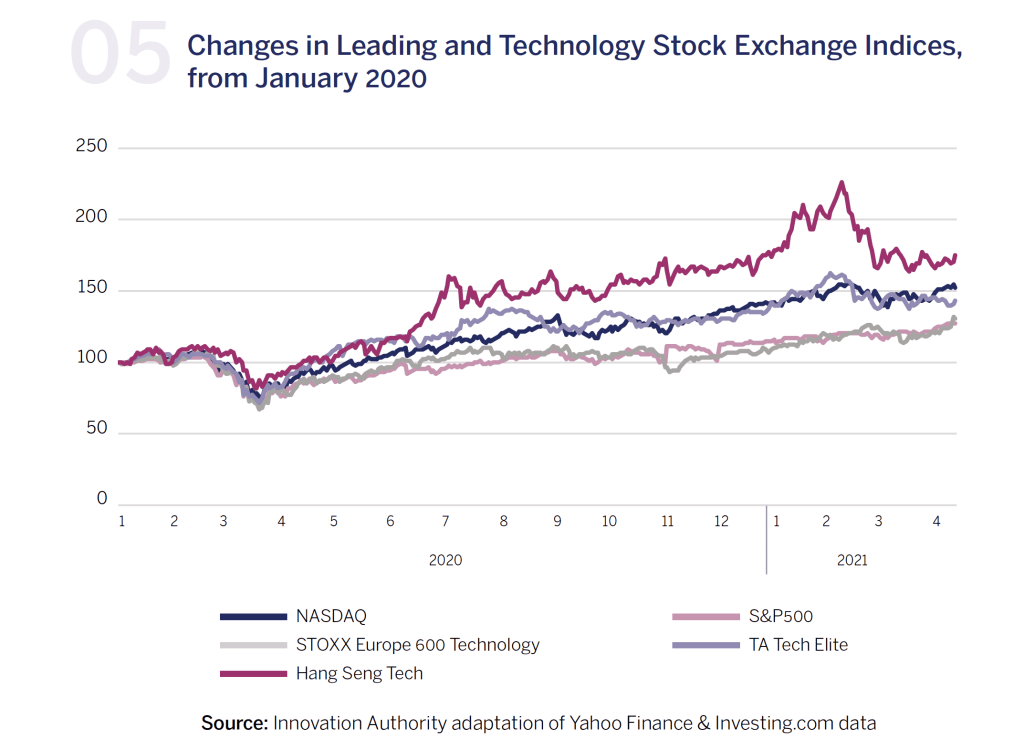

The Israeli economy, like that around the world, is expected to change after Covid. At the new point of equilibrium, some economic sectors will experience growth in demand while others, it seems, will decline. Nevertheless, and despite the uncertainty, one of the trends about which there is relatively broad consensus is, as mentioned above, the rapid growth in the information technology economy. A survey of various global share indices reveals that, as a rule, the more a country’s index is weighted towards technology, the better its performance. The rise in the various technology indices reflects an expectation of the demand for technology and Israeli high-tech must take advantage of this trend, not just for rounds of capital raising but also to expand the diversity of clients and network of connections. For example, global companies that are not necessarily in the high-tech industry, are reorganizing the structure of their supply chain to lower risk and are striving to expand their range of suppliers and their geographical deployment. This development is an opportunity for companies to create new connections.See for example: “Business Beyond Covid-19: The Future of Global Supply Chains”.

When will High-Tech Reach the Public Sector?

The next main question on a national level concerning high-tech’s connection to the Israeli economy for bolstering its recovery relates to the public sector. Israeli technology companies are developing innovative technologies on an international level whereas Israeli citizens, employed in those same companies and who are responsible for the innovative developments, receive state services that are inefficient, not sufficiently digital, and not of the standard expected in the 21st century. According to the UN E-Government Survey, the government digital services index is dropping and Israel’s position in the E-Government Index has dropped from 16th in the world in 2012 to 30th in 2020.UN E-Government Knowledgebase, Online Service Index. In practice, a situation has arisen whereby “the shoemaker walks barefoot” and a dissonance exists between the Israeli technologies available in Israel and their implementation in the local public sector. The Covid crisis has created an opportunity to lead a change in regulatory perception aimed at easing the assimilation of technologies in the public sector.

During the Covid crisis, and within a short period of time, the private sector made a significant quantum leap forward which, in other circumstances, would have taken years to achieve. This included the adaptation of products and services to the digital era and a transition to a work environment out of the office or to one that was adapted to the restrictions of social distancing. The economy in general, and specifically government departments, can learn from the experience of the high-tech sector and the Innovation Authority to advance assimilation of existing technologies in the economy’s various other sectors, including government departments. To enable the public sector to take the necessary steps forward to close the gap that has widened during the Covid crisis, the government departments must become digital and suited to the modern era. The question is how high-tech can aid the economy’s recovery as it exits the Covid crisis.

One of the possibilities to reduce the disparity between the private and public sectors is by harnessing local high-tech to digitize Israel, and its government departments, and prepare them for the post-Covid world. To achieve this, government departments must make an effort to adopt technological solutions, including those in the pilot stage, that will enable the public sector to take the necessary leap forward and transform the government into an ‘Early Adopter’ i.e., for the government to become a client of the high-tech sector via a transition to digital services. One of the primary changes that will facilitate this process is updating the government procurement process and increasing its flexibility e.g., changing the method of tenders and creating new regulations to address the transfer of government data to suppliers while safeguarding privacy. In the field of digital health, for instance, there is an increasing trend of proving product feasibility based on real figures known as ‘Real World Evidence’, beyond proof of concept that is based on controlled clinical trial data. The health system in general, and the health funds particularly, are in possession of vast data and, via collaborations with Israeli digital health companies and the health system, can guarantee a global advantage for Israeli technology companies that will lead the health system to the forefront of technological progress. A change in regulatory perception in the area of procurement will make the state more innovative and efficient, one that provides better service to its citizens via cooperation of both the private and public sectors.

Another aspect of harnessing high-tech to economic recovery is related to utilization of human resources and restoring the unemployed to the workforce. The Covid crisis emphasized employees’ lack of occupational stability and the need to allow them to move between sectors and transfer their services to digital avenues. For example, employees in the tourism, hotel, aviation, and retail industries were prominent among the those adversely affected. Some of these sectors are also exposed to risks other than Covid. The tourism industry, for example, is influenced by geo-political events and its employees suffer from occupational instability. The employees in these industries, who are used to customer service and in many cases speak other languages, may have opportunities in the mature high-tech companies developing in Israel (and which were analyzed in the Financing Chapter) that need employees in a variety of non-core technology jobs. It is possible to retrain employees from sectors other than high-tech and place them in these jobs e.g., human resources management, sales, and customer relationship management.

However, high-tech retraining is not a simple process. As detailed in the Human Capital Chapter, inexperienced employees (juniors) have difficulty finding work in high-tech companies and a concern therefore exists that even those employees from other fields retraining in high-tech will still encounter difficulties in finding work. Therefore, every such training program must also be accompanied by a detailed plan addressing placement of the participants and finding them employment in the field in which they are trained. One possible solution to this problem is to employ retrained juniors in the public sector, as we described in the Human Capital Chapter.

Government Tools for Advancing High-Tech as a Growth Engine

The Covid period emphasized the need to quickly formulate and implement state solutions during crises as a response to a changing reality. At the beginning of the Covid crisis, the expectation for an extended period of low interest rates and investors’ moderated propensity for risk highlighted the limitations of Bank of Israel interest rates as a tool for increasing demand and the importance of state support for the economy, both by injecting money and via regulation. Two examples illustrating the potential of implementing government supportive tools in high-tech are presented below.

One of the examples for the way in which updating regulation can facilitate the creation of a new market is the Israeli Drone Initiative (National Drone Delivery Network). The NAAMA Initiative was established in January 2020 in conjunction with Ayalon Highways, the Civil Aviation Authority, the Ministry of Transport, and the Smart Mobility Initiative as part of the activity of the Authority’s Center for Regulation of Innovative Technologies that advances regulation to develop and implement innovative technologies.The Center for Regulation of Innovative Technologies was established at the Authority in 2019 together with the World Economic forum (WEF), based on Government Resolution No. 4481 from January 2019. The aim of the project is to create a national network of autonomous drones for the delivery of cargo transportation in urban areas that will be ready for commercial use within three years. As part of the initiative, the center, together with Ayalon Highways, the ICAA, and the Ministry of Transport created a unique regulatory framework within a designated geographical area that will enable test flights of drones in the Hadera region which are fully monitored by an integrative control system. This is a groundbreaking development on a global scale, both in essence and scope, because operating a drone in an urban environment also constitutes a regulatory challenge for the European Aviation Authority and the American Aviation Authority together with NASA. More than 2,400 real flights were conducted in Israel during the Covid period by six companies as part of the program’s final demonstration stage. Seven further demonstrations are expected in the future as part of the joint Initiative-Innovation Authority pilot and more will be conducted throughout the country in conjunction with the health system. This activity is just one example that illustrates the potential that exists when creating “regulatory sandboxes” as a foundation for collaboration between state entities and the private sector. Creating such collaborations is one of the Authority’s central areas of activity and is carried out both via the Center for Regulation which supports the regulatory aspect and the incentive programs that support the pilots.

The most striking example of the way in which swift state intervention via investment can create growth in response to a need created by a crisis is the Authority’s Fast Track Incentive Program launched together with the Ministry of Finance. The initial Covid period was characterized by a decline in the injection of capital investment from the private market to innovative technology companies which were considered high risk.

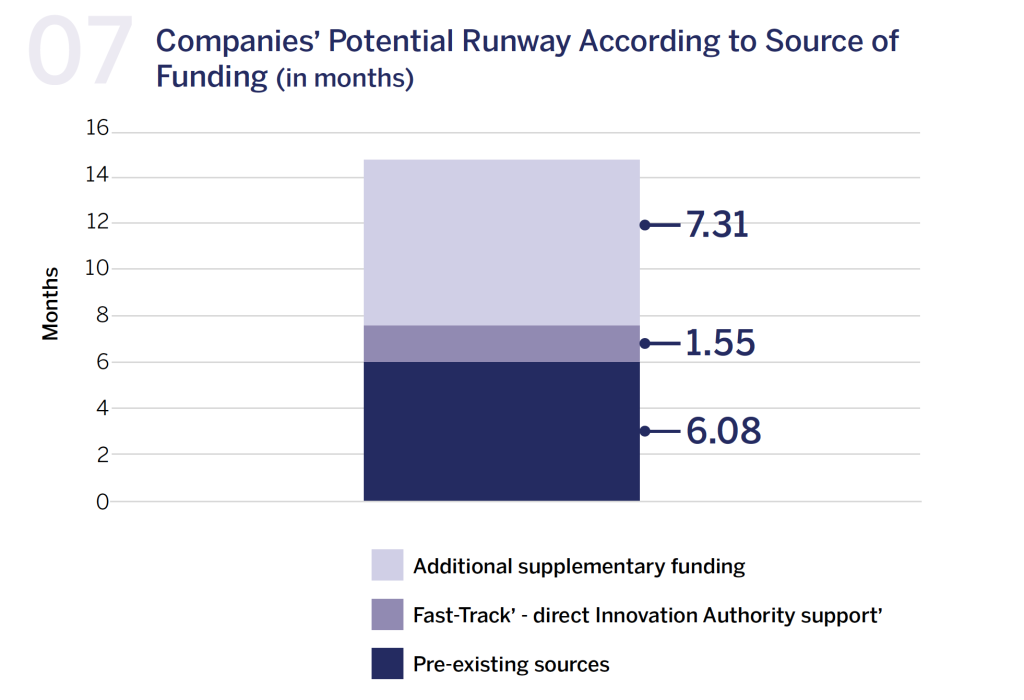

At the outset of the crisis, it was decided to create a solution for innovative technology companies that had already accumulated fundamental assets, and which were in early growth or R&D product development stages, had good long-term success prospects, but that faced a short-time funding crisis (a short ‘runway’ of up to 12 monthsThe term “Runway” refers to the period in which a company can continue operation and is calculated by the relation between the pace of expenditures and cash balance.). The Fast-Track Program enabled to check these companies and provide an answer within only four weeks, each company able to submit a request for support of R&D programs of up to NIS 15 million.

The program awarded NIS 650 million during its seven months of operation, with 283 requests being approved (out of 578 submitted) at an average support rate of 46% of the approved budget. Receiving a grant from the program was conditional on the company recruiting matching funding from private investors.

Analysis of the companies’ “runway” after receiving funding via the Fast-Track Program showed that it achieved its objective: the companies’ average runway grew from 6 months before receiving the funding to approximately 14 months after funding. The Fast-Track Program’s success is highlighted when comparing the Israeli venture capital market’s performance and the scope of capital raised by early-stage high-tech companies to parallel figures in the US and in Europe where a decline in the number of funding rounds was recorded. The swift intervention of the Innovation Authority and the conditioning of its support on supplementary funding contributed to the speedy return to the market of early-stage investors and to the accelerated growth of startups during the crisis. The program’s success raises the question as to whether high leverage state tools should also be provided during non-crisis periods, a question that is currently being examined by the Innovation Authority.

With a look to the future, there is also room to examine the support tools provided to the manufacturing industry in Israel. This industry has matured and is no longer at the stage where there is a need to provide it access to the worlds of innovation. Most production plants today realize that without introducing significant innovation into their products or production lines, they can expect to struggle and even perish in the face of global competition, whether their activity includes export or is restricted to the local market and contends with competition from imports. Considering the local market’s growth, manufacturing plants must find the niches in which they can produce and export unique and innovative products from Israel. Adopting technologies from the world of Industry 4.0 is perhaps a prerequisite for survival, however because this is a global trend with investments on a scale which Israeli industry cannot meet, extra innovation is needed either in the products themselves or in their production technologies.