High-Tech During Covid – Innovation Authority Report 2020-2021

From many perspectives, Israeli high-tech has never enjoyed a better period. The industry seems to be constantly growing and Israeli startups are attracting increasingly large investments and achieving significant commercial success. High-tech employees continue to be a strong group and benefit from excellent employment conditions compared to their counterparts in other industries. Nevertheless, it is specifically the Covid pandemic and resultant global economic-health-social crisis that has highlighted the challenges faced by the industry which has immense importance for and makes a significant contribution to the Israeli economy. Furthermore, the need to contend with these challenges stresses the need to ensure high-tech’s long-term global success because of the extent to which the Israeli economy depends and is based on this sector. Crises in Israeli high-tech may cause critical damage to employment, state revenue from taxation, pension incomes, and the stability of the Israeli economy at large.

In the “High-Tech During Covid” 2020-2021 Report published by the Innovation Authority (hereinafter: “The Authority”), we present the high-tech industry’s central finance and human resources challenges. The report also examines the industry’s opportunities to contribute to the economic recovery from the Covid crisis by connecting it to the business and public sectors of the economy in order to accelerate digital transformation and the implementation of technological progress in Israel. Covid has highlighted the gaps that exist between high-tech and the rest of the State of Israel with regard to how to contend with crises, a quick transition to working from home, adaptation of the work environment, and utilizing the new business opportunities that have been created.

Israeli high-tech demonstrated substantial resilience to the Covid crisis thanks to its ability to react quickly to the new work environment and conditions of uncertainty. High-tech indices continued to rise, including the Innovation Authority’s High-Tech Index that presents an aggregated situation report of the Israeli high-tech industry and the changes it has undergone. For more details on the High-Tech Index, see Appendix. This contrasts with the other sectors of the economy in which the economic shockwaves had a more severe impact. At the same time, the demand for employees in technology professions remained high throughout the crisis – even though the shortage in employees declined from 19,000 to 13,000 available high-tech jobs, as can be seen in the Human Capital Report published by the Authority. The ratio of unemployment benefits recipients in high-tech reached a record level during the Covid period of almost 14% during the first lockdown. This is 7 times higher than the parallel ratio prior to the Covid crisis which stood at only 2% as of January 2020. In the other sectors of the economy, the ratio of unemployment benefits recipients during the first lockdown was however double. The rate of unemployment in high-tech also rose during subsequent lockdowns although the gap compared to the economy in general narrowed. With the economy’s return to normal activity, the rate of unemployment in high-tech as of April 2021, stands at 8.2% – still 4 times higher than that prior to the crisis. Nonetheless, given the rise in the number of total employees in the high-tech industry, concern exists that these unemployed high-tech professionals are not expected to find employment in the near future.

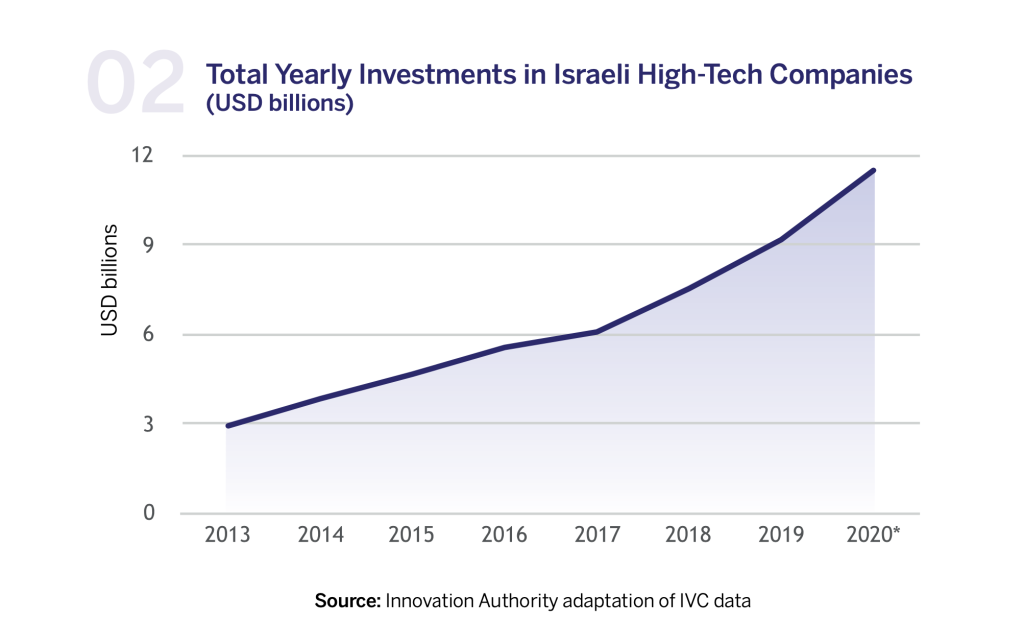

Most high-tech employees who lost their jobs during the Covid crisis earned relatively low salaries compared to the industry i.e., less than NIS 15,000 a month. As a result, it can be concluded that most of the harm in high-tech employment was to young employees (“juniors”) and auxiliary employees who generally earn less than the average high-tech salary that, in 2020, stood at NIS 25,300. Experienced employees in core-technology high-tech professions were impacted less than the generally severe economic effect of the crisis and its influence on the general economy. The primary characteristic of the current period for Israeli high-tech is the industry’s maturation. More Israeli startups than before are choosing to preserve their independence and to grow as complete companies with large numbers of employees, leading significant business activity worldwide. The capital raised by Israeli startups more than quadrupled within a decade and stood at USD 11.5 billion in 2020, 20% more than the total raised in 2019, while the average funding round for startups rose by 10% in 2020 compared to 2019. Most of the growth in investments is in the sums raised by advanced-stage startups with some unprecedented sums of hundreds of millions of dollars in each investment round. Within just 5 years, the number of investments exceeding USD 100 million has grown almost seven-fold from 3 such investments in 2015 to 20 in 2020. Furthermore, in Q1 2021 alone, 20 investments exceeding USD 100 million were finalized.1Innovation Authority adaptation of IVC data, The Israeli Tech Review Q1 2021.

The leading fields in Israeli startups investments are cyber and FinTech which attracted the largest amount of capital in 2020. Against the backdrop of the Covid crisis, the sector with the next highest number of funding rounds after the cyber sector was that of startups in the field of digital health – a field characterized by growing global demand. Furthermore, companies using Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies raised more than USD 4 billion in 2020. High-tech exports also rose consistently and reached almost USD 50 billion in 2020 – more than 40% of total Israeli exports. The number of stock offerings by Israeli startups that are growing and maintaining their independence, reached a record of 31 IPOs in 2020, primarily on the Tel Aviv and Wall Street stock exchanges. Compared to 2019, the number of stock offerings by Israeli technology companies in 2020 rose by more than 50%. The Israeli companies are utilizing the opening of the global stock offerings window and several other Israeli companies are preparing to raise capital on the stock exchange, an indication that, considering the 23 stock offerings held during the first quarter of 2021, this trend is set to continue in the foreseeable future.2Innovation Authority adaptation of Startup Nation Central data. At the same time, since the record levels of 2015, there has been a consistent decline in the number of new development centers opened by multinational companies that generally locate their activity in Israel following acquisition of or merger with a local startup. In 2020, only 4 new centers were opened. As for mergers and acquisitions, the number of transactions dropped from 148 in 2019 to 109 in 2020.3Innovation Authority adaptation of IVC data, The Israeli Tech Review Q1 2021.

Nevertheless, it is important to monitor several worrying indices and examine their long-term significance. Following the growth in entrepreneurial activity in Israel a decade ago, recent years have seen a significant decline in this important metric which checks the number of new startups established each year. This decline raises the question as to whether Israel is at the end of the startup nation era. Within five years, the number of new startups established in Israel has plummeted from 1,400 in 2014 to approximately 850 new companies in 2019, and about 520 in 2020.4This estimate will be updated and is expected to increase in the near future. However the decline trend will probably continue and is expected to be lower than that of 2019. The number of new startups established in the last two years is similar to the levels recorded in Israel a decade ago, this despite the subsequent growth and development of the local innovation ecosystem. The number of new startups established each year will have an influence on Israeli high-tech in the future and the question arises as to the minimum number of companies needed to preserve Israel as a startup nation. As of now, the number of seed investments – investments directed at new startups – has not declined further, while there has been a significant increase in investments attracted by growing startups at more advanced financing stages. The number of investors participating in investment rounds of early-stage startups has declined over the previous two years, especially in seed stages. The first chapter of the report – “Is this the end of the Israeli ‘Startup Nation’ era?” – addresses the issue of financing and presents extensive details regarding the issues described above.

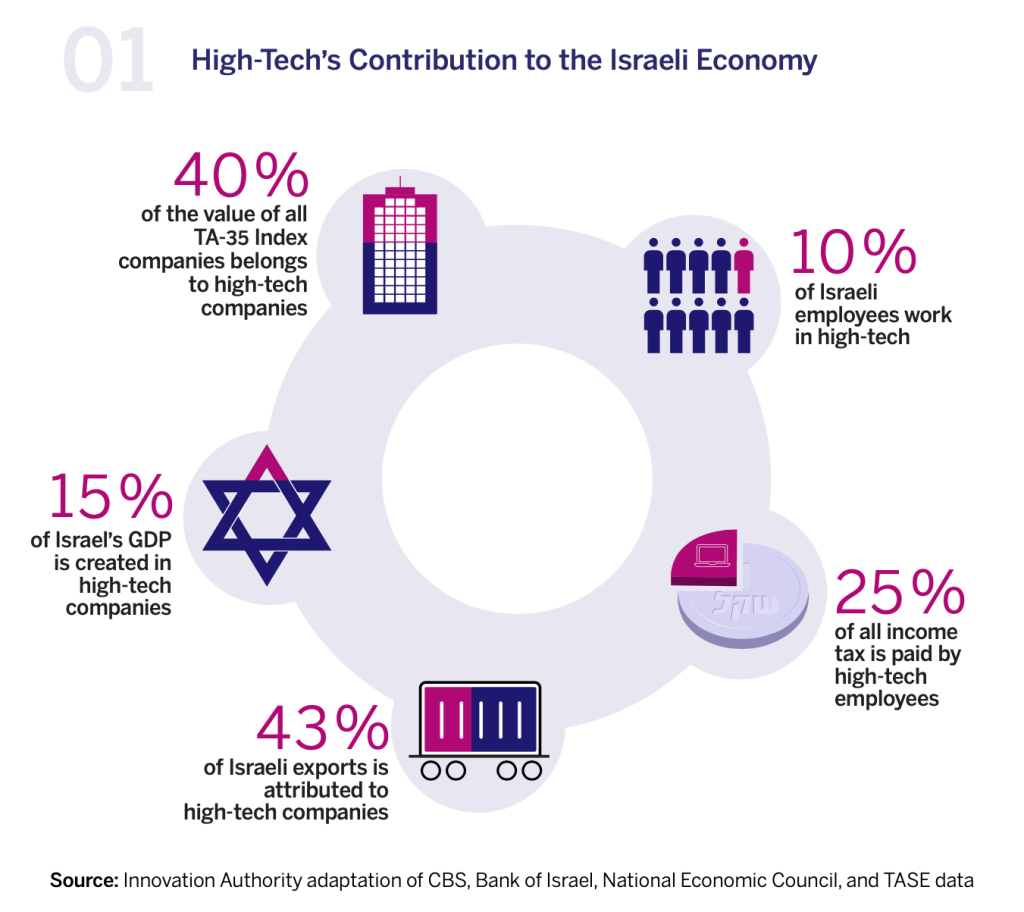

As mentioned, the competition over human resources in high-tech continued throughout the Covid crisis when, despite the rise in unemployment among low salaried high-tech employees, there was a continued shortage of experienced employees sought after by high-tech companies. The large sums raised by Israeli startups are also, to a large degree, intended to increase the companies’ personnel in a range of jobs. High-tech professionals make a significant contribution to the rehabilitation of the economy, which needs to recover from the economic-social-health crisis and to create new sources of income to lower the budget deficit. The employees in the high-tech industry, who earn more than double the overall average salary and who comprise less than 10% of all employees in Israel, are responsible for one quarter of all tax revenues from salaried employees. The employees in multinational companies’ development centers are responsible for tax payments more than six times higher than their relative share of the Israeli labor market.

This report also discusses in detail several other long-term trends related to high-tech human resources. The first is the increase in age of high-tech employees which reflects the industry’s maturation. In contrast to high-tech’s image as a young industry, in recent years there has been an increase in the employees’ average age that is now even slightly higher than the average for the whole economy. The average age of high-tech employees in 2019 stood at 40.1 compared to the average employee age of 39.6 in the overall economy. A second trend is the rise in the rate that university graduates are entering the industry, a trend that should lower the shortage of high-tech employees. The most popular course of study in Israel during the current academic year is a bachelor’s degree in engineering studied by more than 18% of all Israeli students. In total, one of every three students in Israel is studying for a bachelor’s degree in STEM subjects (science and high-tech), 64% of whom (55,000 students) at Israeli universities. One in every four students in Israel is therefore studying for a bachelor’s degree in a technology-oriented subject such as engineering or computer science.

On the one hand, this is excellent news for the high-tech industry that suffers from a chronic shortage of employees. On the other hand, the flow of fresh graduates may exacerbate the existing problem of juniors and makes it difficult for them to find work without prior experience in the field. In the years to come, tens of thousands of new employees with academic technological training will take their place in the high-tech workforce but with only limited, if any, experience. If a third of the students in Israel continue to choose science subjects, more than 20,000 employees with limited experience will join the high-tech industry every year by 2030. To contend with this problem and ensure that the fresh graduates do not remain unemployed, high-tech employers, including mature Israeli startups, will need to develop avenues for hiring and training inexperienced employees. Today, the companies are interested in experienced employees and many of them are unprepared for training young employees. Coupled with this problem, are the high salaries in high-tech that are increasing sharply with the strengthening of the shekel against the dollar. These salaries make Israeli employees expensive and increase companies’ expenditures, compared to solutions such as outsourcing that enable the employment of experienced employees at low costs. With respect to the makeup of the industry’s employees, Israeli high-tech continues to preserve its status as a homogeneous and relatively closed circle based primarily on non-ultra-Orthodox Jewish men who comprise two thirds of all high-tech employees. The ratio of ultra-Orthodox and Arab employees in the high-tech industry remains low at 3% and 2%, respectively. With respect to women, it is noteworthy that although the number of women students choosing to study computer science has risen by approximately 130% since 2010, and those choosing to study engineering has increased by 50%, they still comprise only a third of all science degree students, similar to their share of the high-tech workforce. As a result, the ratio of women in technology jobs in the high-tech industry is also expected to remain steady at about one third in coming years.

An extensive discussion of high-tech human resources, including the importance of cultivating complete Israeli high-tech companies with employees from a range of roles, is presented in Chapter 2 – “What Will the Future High-Tech Generation Look Like?”

How Can We Guarantee High-Tech’s Continued Success?

The government laid the infrastructures that has enabled the growth of high-tech since the 1970s, and especially, in the early 1990s. Since then, high-tech has grown and evolved into an important sector of the Israeli economy, and growth in recent years has occurred almost without government intervention. High-tech’s share of GDP increased from 10% in the 2000s to 15% in 2020, with most of this growth occurring in the last 3 years. The latest Bank of Israel report stated that high-tech’s significant share in the Israeli economy is one of the factors that led to the moderate adverse impact of the Covid crisis in Israel compared to its influence in other developed countries. Another angle of this picture is a study conducted by the Innovation Authority revealing that if Israeli high-tech companies that are traded on foreign stock exchanges would register on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange, the total value of all the companies comprising the Tel Aviv-35 Index would jump by more than 70% and the weight of the index’s high-tech companies would stand at approximately 70%, compared to 40% today. Therefore, although it seems that high-tech is successful and thriving, the government’s role is to ensure that the industry’s resilience and stability remain intact. The question arises as to the areas that require government intervention because the future of the Israeli economy depends, to a large degree, on the future of high-tech.

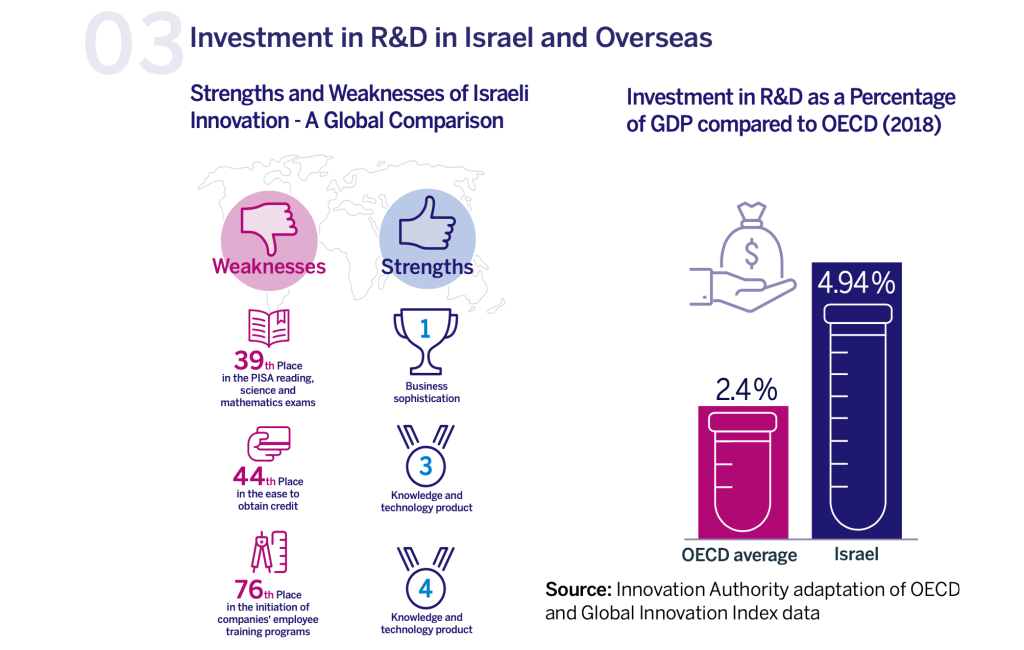

Today, Israel continues to maintain its leading position in the metric of R&D investments as a percentage of GDP. Nonetheless, high-tech is currently contending with several challenges that could influence its global competitiveness. Israel’s global competitive status as the ‘Startup Nation’ is being gradually eroded, and in recent years Israel has been dropping down global innovation indices. For example, for the second year running, Israel has dropped in the Global Innovation Index published by Cornell University, the World Intellectual Property organization, and the INSEAD Business School – in 2018 Israel was ranked 10th, in 2019 – 11th, and in 2020 – in 13th place. With respect to government support for the high-tech industry, the Innovation Authority’s budget as a percentage of the state budget has dropped sharply, from 1% in the early 2000s to less than 0.5% today. This support equates to 0.15% of GDP, while the scope of government support for innovation in the EU and other countries such as Korea and the US stands at between 0.6%-1% of GDP. The shortage in personnel and the strong shekel make it difficult for high-tech employers and these are also fields in which the government can play an important role.

Government departments need to digitize and adapt themselves to the new era, and regulation must place technological progress at the forefront of its considerations.

The third chapter of the report – “How can Israeli High-Tech Help Rehabilitate the Economy?” – discusses several operative directions in which the government can aid the future of high-tech and continue to lay foundations for national infrastructures that will allow it to flourish, as it did in the past. These efforts must focus on all relevant fronts: continuation and expansion of quality personnel training in outstanding world-class academic institutions; adapting regulation to support implementation of the future generation of technologies in fields such as drones and autonomous vehicles; and the building of a set of incentives to grow “complete” companies, including the creation of competitive tax laws that will encourage Israeli and multinational companies to manage, operate, and produce in Israel and thereby continue to hire and increase the number of their employees in Israel, despite the high costs involved.

Among others, the government in general, and the Innovation Authority in particular, must continue to identify the fields of the future technology the world is headed for and that require heavy investment in the creation of national research infrastructures, the training of quality human capital, providing advanced-technology infrastructure, and in long-term planning. A prominent example is the field of Bio-Convergence (multidisciplinary research that combines engineering and biology), in which the Authority is investing substantial effort to fully utilize the resources of knowledge and personnel that are under-represented in biology fields.

The funding needs of startups and their ability to raise capital changed immediately with the outbreak of the Covid crisis. The Innovation Authority immediately took on this challenge and offered new solutions suited to the new reality. One of the prominent examples of a government solution developed in response to the crisis is the Fast-Track Program created by the Authority together with the Ministry of Finance. This program is intended to help startups traverse the initial crisis period that was characterized by a decline in the injection of private market capital to innovative technology companies, the investment in which involves high risk. The program awarded NIS 650 million during its seven months of operation, with 283 requests being approved (out of 578 submitted). Approval of the requests was conditional on the company recruiting matching funding and contributed to the speedy return to the market of early-stage investors. This solution illustrates how swift government intervention can create growth, in this example via investments, even in times of crisis. It also serves to teach of how further government solutions can be offered and suggests that it is worthwhile examining how this approach can be adopted routinely.

Another example is the program to encourage institutional entities’ investment in Israeli high-tech companies in early sales and growth stages via the Israeli capital market. As part of the program, the Innovation Authority’s Investment Committee approved the securing of NIS 2 billion worth of investments in high-tech companies. Further initiatives and legislative changes are currently awaiting Innovation Authority attention. These are aimed at supporting current challenges and opportunities related to funding of innovation and Israeli high-tech companies, and include the new Angels Law, an easing of regulation pertaining to the acquisition of foreign companies by Israeli companies, and a change in tax regulation on foreign loans for high-tech companies.

The next central question on a national level relates to connecting high-tech to the Israeli economy, especially to the public sector, government departments, and other highly regulated sectors, in order to revive the economy after the Covid crisis. Israeli technology companies are developing innovative technologies on a global level, while Israeli citizens, employed in those same companies and responsible for the innovative developments, receive state services that are inefficient, not sufficiently digital, and not of the standard expected in the 21st century. The Covid crisis has now created an opportunity to lead a change in regulatory perception to ease the implementation of technologies in the public sector and in highly regulated and regulation-oriented sectors.

During the Covid crisis period, the public sector underwent a rapid and significant quantum leap which in other circumstances would have taken years to achieve. This included the adaptation of services and products to the digital age and a transition to a work environment out of the office or one adapted to the conditions of social distancing. To enable the public sector to take this same necessary step forward and to close the gap that widened during the crisis, government departments must digitize and adapt themselves to the new era. In turn, regulation must place technological progress at the forefront of its considerations. The question is how high-tech can assist the economy’s recovery following the Covid crisis. One example of how updating regulation enables the creation of a new market is the National Drone Delivery Network Initiative that is aimed at creating a national network of autonomous drones to deliver cargo in an urban area, that will be ready for commercial use within 3 years.

Government departments need to digitize and adapt themselves to the new era, and regulation must place technological progress at the forefront of its considerations.

Covid adversely affected many sectors of the economy where activity was suspended or severely limited, such as tourism and aviation, due to global restrictions on movement. Nevertheless, the crisis also created new opportunities for the Israeli economy and reinforced pre-existing trends. One such quantum leap on a national level is the transition to a digital economy and e-commerce. The closing of stores led many businesses to offer their wares online for the first time, while consumers also increased their use of digital services. A new point of equilibrium has now been created where the number of users of e-commerce sites is higher than it was prior to the crisis. The government must take the opportunity created by this trend which has only been accelerated by the Covid crisis, to increase businesses’ productivity and support business opportunities made possible by e-commerce, including opening Israeli businesses, that until now had focused on the local market, to international trade. The growth of Israeli businesses is fundamental to the economy’s recovery following Covid, to the creation of new jobs, and to improving the services Israeli consumers enjoy today.

A further example of a national quantum leap forward that would not have been possible without Covid and which the state profits from is the transition of organizations from all sectors of the economy to working from home. Covid forced organizations that had never previously considered this option or even objected to it, to experience a new work environment. Now, many of them are considering or have already decided to move to a hybrid work model that combines work in the office and working from home, even after Covid. A first positive sign of regulation encouraging this direction came from the Wages Commissioner’s Division in the Ministry of Finance and the Civil Service Commission who allow employees in the public sector to work from home one day a week. The hybrid work model preserves several advantages for the economy of working from home that were highlighted during the Covid period. For example, it allows to reduce traffic on the roads and for employees to live in areas far from centers of employment. Adopting a hybrid work model requires a fast high-quality internet infrastructure throughout the country that the state will be responsible for laying, to address cyber security issues, to resolve taxation and work relations issues pertaining to working from home, and to examine the adjustments and training necessary in human resources to enable this change in the long-term.

We invite you to read the in-depth discussion of these and other issues presented in the report that are expected to shape and influence the Authority’s policy and activity.