Despite the two countries’ cultural and commercial differences, Israeli and Korean innovation complement each other. The challenge: to bridge the gaps and advance the mutual commercial R&D relations between the two countries.

A synergetic relationship, based on complementary contrasts, exists between the State of Israel and the Republic of Korea (hereafter: Korea) in the fields of innovation and commerce. In general, the two countries have much in common from historical and geo-political aspects: Similar to the State of Israel, Korea was only declared an independent state in 1948 and has since undergone accelerated economic development; it has been in the midst of a continuous state of conflict with its northern neighbor; and its natural resources are sparse. However, in contrast to Israel, the Korean population is homogeneous, numbers approximately 50 million and has a continuous 4500 years tradition in the Korean peninsula.

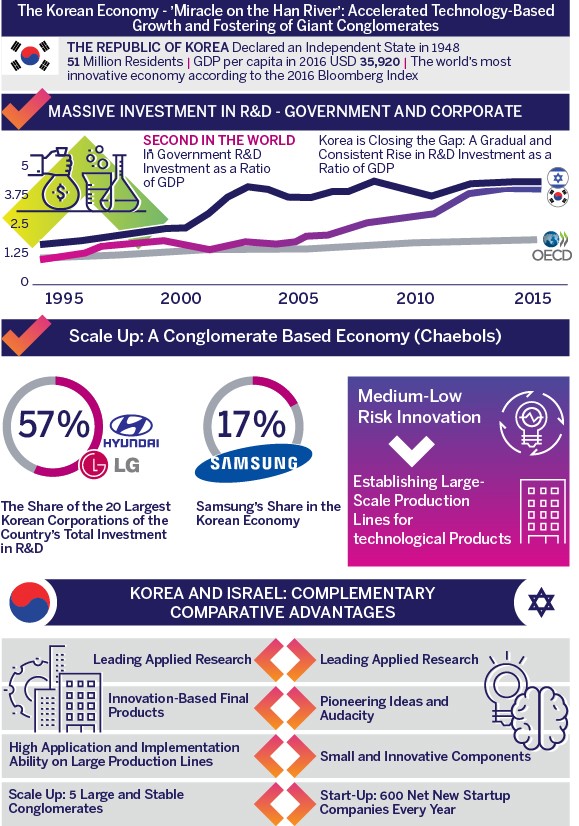

A spotlight on the business culture in the two countries reveals fundamental differences between Korean and Israeli innovation. The Koreans specialize in the gradual growth of small and medium sized companies to large corporations, and in the establishment of a complete production chain via advanced technology. In contrast, Israelis excel in establishing small startup companies around a ground-breaking idea.

By virtue of these complementary comparative advantages, successful Israeli-Korean ventures have developed during recent years that contribute to the economies of both countries. These mutual relations have evolved with the support and encouragement of the Korean and Israeli governments, especially via the KORIL-RDF (Korea/ Israel Industrial Research and Development Foundation), the bi-lateral Korean and Israeli R&D Fund that was formed in 2001 following the strengthening of relations between the two countries (see below). Up to 2016, over 140 joint Israeli-Korean corporate technological innovation projects were launched with a total scope of approximately USD 54 million.

The Secret of Korean Success: State Investment and Growth of Giant Conglomerates

The names of the large Korean conglomerates, such as Samsung, LG, Hyundai, SK and Kia Motors are recognized all over the western world. It sometimes seems as if Korea has always been a focus of economic and technological prosperity, but that is not so. During the first half of the twentieth century, Korea was subject to Japanese occupation that lasted for 35 years. This was the last occupation in a series of foreign conquests that began thousands of years ago. Upon conclusion of the Second World War, the world powers attempted to establish a united independent state in the Korean peninsula. The failure of these efforts led to the outbreak of the Korean War between the communists in the north and the anti-communist forces in the south. In 1953, following three years of fighting, a ceasefire was declared and the current division between the two halves of the peninsula became permanent. The Republic of Korea, an agrarian and completely devastated country in the wake of the war, began an accelerated process of rehabilitation. A momentum of construction and innovation were accompanied by a national sense of total commitment to the state and its success, and by an underlying understanding that growth was the only way forward after the low point at the conclusion of the war.

It was during these years that the infrastructures of the modern Korean economy were laid. The authoritarian regime that ruled during the post-war era established a quality education system the graduates of which comprised fertile ground for the absorption, assimilation and subsequent development of technology. The regime also established a technical university and many research institutions in a technological park that developed into a flourishing complex. This process, termed “The miracle on the Han River”, transformed Korea from a poor agricultural economy into one of the wealthiest and most developed in the world, the product per capita of which has grown from 605 dollars in 1970 to 35,920 dollars in 2016.1 2

Over the years, the Korean government has acknowledged the significance of technological innovation for national development, and therefore invested, and is still investing, vast funds in research and development, especially in the fields of ICTCampbell, J. (2012). Building an IT Economy: South Korean Science and Technology Policy. Issues in Technology Innovation, vol. 19, 2012.. The rate of R&D investment in Korea thus doubled between the years 2000-2015 and stands today at 4.23% (as of 2015).Van Noorden, R. (2017, February 7). Israel edges out South Korea for top spot in research investment. Nature. http://www.nature.com/news/israel-edges-out-south-korea-for-top-spot-in-research-investment-1.21443?WT.mc_id=TWT_NatureNews The level of state expenditure on research and development is particularly high when compared to other developed countries, and stands at approximately 1% of GDP.OECD figures for 2014

To illustrate, a national R&D program launched in 1982 encouraged investment in R&D in the corporate sector by means of funding R&D, providing tax benefits and other incentives, and emphasized the companies’ competitiveness in international markets. Between 1982-1993, this program resulted in 2412 projects at a total cost of approximately 2 billion dollars, of which the government financed approximately 58 percent. The program’s success was reflected in the creation of 1384 patents and the development of 675 commercial products.Lall, S. (1999). Promoting Industrial Competitiveness in Developing Countries: Lessons from Asia. London: Commonwealth Secretariat. Pp. 51-52.

Today, the country is harvesting the fruits of its investment: Korea was ranked as the world’s most innovative economy according to the Bloomberg Index in 2016.Lu, W. and Jamrisko, M. (2017, January 7). These Are the World’s Most Innovative Economies. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-01-17/sweden-gains-south-korea-reigns-as-world-s-most-innovative-economies?leadSource=uverify%20wall Koreans themselves enjoy the fastest internet connection in the world, high availability of mobile telephones, and a well-deserved reputation as early adopters of technology.Son, J. (2017, March 4). South Korea has World’s Fastest Internet. http://technology.inquirer.net/59866/south-korea-worlds-fastest-internet; The ICT Development Index of the ITU can be seen at: http://www.itu.int/net4/ITU-D/idi/2016/. The 2016 ICT Development Index of the United Nations ITU (International Telecommunication Union). See the ITU website: http://www.itu.int/net4/ITU-D/idi/2016/

A further aspect of the accelerated rehabilitation process included significant government support for several conglomerates under family control (known as “Chaebols”), considered central partners for implementation of the state program of growth and industrialization. The Korean business approach espouses ‘Scale Up’: gradual growth in a comprehensive, fundamental and continuous manner. Over the years, Koreans have specialized in the establishment of small and medium-sized companies and their scale-up into conglomerates, while relying on widespread recruitment of skilled personnel, generous government resources and large injections of funds at the beginning of each new project. Today, the conglomerates function as the country’s economic backbone, while the largest, – Samsung – constitutes approximately 17% of the entire Korean economy. The Samsung Group was founded in 1969 and is today comprised of nearly 80 subsidiary companies developing, producing and marketing in a wide range of fields such as electronics, engineering, shipbuilding, construction, retail & leisure, insurance, medical services and others, in which hundreds of thousands are employed.

The conglomerates are also a major focus of technological innovation and each of their business-technology divisions includes an in-house R&D Institute. In this manner, while the private sector’s share of total R&D investment stands at 75%, the 20 largest corporations in Korea’s share of the total R&D investment is approximately 57%.Chung, S. (2007). Excelsior: The Korean Innovation Story. Issues ןn Science and Technology, Volume XXIV Issue 1. http://issues.org/24-1/chung/

The Korean Economy: From Moderate to Pioneering Innovation

Although the total commitment to success which guided rehabilitation from the war contributed to industrial and military development and to the establishment of the conglomerates, at the same time it created a parallel business culture of fear of failure resulting in moderate innovation. The conglomerates traditionally inclined towards low-medium risk technology projects. They chiefly specialized in the creation of innovation-based large production lines for complex products, and less in the actual development of innovative components and pioneering technologies.

In recent years, it appears as if Korea is aspiring to prepare for a transition from moderate innovation to groundbreaking innovation. This trend is reflected in a young generation of innovators who are striving to establish innovative start-up companies, and in the parallel initial signs of proposals to finance independent innovation. Additionally, the conglomerates themselves are becoming pioneers in different sectors. For example, Samsung was a pioneer in the field of 3D NAND Flash MemoryTeam TS. Samsung continues to lead global NAND flash memory market. TechSource. March 2017. https://www.techsourceint.com/news/samsung-continues-lead-global-nand-flash-memory-market and, together with LG, is at the innovation forefront in the area of OLED screens.Shankar B. (2017). LG to release its first-ever OLED smartphone in Q3 2017 says report. https://mobilesyrup.com/2017/05/16/lg-to-release-its-first-ever-oled-smartphone-in-q3-2017-says-report/

At the same time, there is a general realization that notwithstanding the significant contribution of the conglomerates to the economy, the typical size and scope of their operation creates an economic centralization and dependency which places stability at risk. This situation was clearly illustrated by the Asian financial crisis in 1997 when fourteen Korean corporations collapsed, causing heavy damage. Subsequently, the government began diverting resources towards small and medium-sized companies that until then struggled to compete with the large conglomerates, and to promote start-up ventures. Just recently, newly-elected President Moon Jae-in transformed the Korean Authority for Small and Medium-Sized Businesses from an Auxiliary Unit to an independent government ministry.Lyan, Irina. 2017. Remapping East Asian Economies. Paper presented in Korea University Graduate Student Conference, June 23.

The Secret of Israeli Success: A Culture of Entrepreneurship Unafraid of Failure

Israel, in contrast to Korea, is a small country with a culture of entrepreneurship that relies on audacity, improvisation and experimenting. While in Korea it is expected that an entrepreneur whose venture has failed will beat his breast and express deep sorrow, business culture in Israel encourages, even admires risk taking and development of pioneering technologies, and acknowledges the benefit of spillover knowledge acquisition even from projects that fail. The serial entrepreneur Dov Moran emphasized this approach in describing his company Modu which developed a modular cellular phone and then closed in 2010. Moran stressed that as far as he is concerned, Modu was not a failure because thanks to the knowledge generated during its operation, 30 other new start-up companies were created.Based on a number of lectures of Dov Moran in Korea, the latest at the Hello Tomorrow Korea Conference within the framework of the Asian Leadership Conference in Seoul, July 2017.

Accordingly, the Israeli high-tech industry is characterized by a large number of innovative start-up companies that are developing pioneering components or technologies. These developments are frequently acquired by a large corporation that will then integrate them into a broader-based system or final product. The central challenge for Israeli innovation today is therefore to grow complete companies and entire value chains- that type of Scale Up in which the Koreans excel.

The Israel-Korea R&D Fund

KORIL (KORIL-DF), the Israeli-Korean binational Research and Development Foundation, was established as the result of a Memorandum of Understanding signed by the two governments in 1998 with the specific objective of advancing industrial R&D via joint technology projects. KORIL operates in conjunction with the Israel Innovation Authority and the Korean Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE). Representatives of the Israeli and Korean governments comprise the Foundation’s Board of Directors. The Foundation’s head office is located in Seoul while an official Israeli representative is situated in Israel. The Foundation’s budget was enlarged to total USD 4 million in 2013, USD 2 million from each country. Its main roles are to assist companies in locating partners for R&D initiatives from both countries; funding direct R&D expenses in collaborations between Israeli and Korean companies which develop unique commercial products based on technological innovation; and the facilitation between partners from Israeli and Korean companies, especially regarding challenges arising from differences in business culture.

Proposals for support for joint initiatives are submitted to the Foundation in three budget models: Feasibility Study, Mini Scale Project or a Full-Scale Project. The Foundation’s decision whether to authorize or reject the proposal is made following parallel due diligence in Korea and Israel. Foundation website: www.koril.org

In Practice: Strategic Cooperation with BondIT

The Fintech company BondIT, founded in 2012, develops learning machine-based solutions for financial advisors, that build and optimize bond investment portfolios. In July 2016, the company signed a strategic cooperation agreement with KIS Pricing, a Korean subsidiary company of the global finance corporation Moody’s. Within the framework of the cooperation, the two companies are jointly developing software for managing bond investment portfolios, with the financial support of the Israel-Korea R&D Fund (KORIL).

The Potential of the Israel-Korea Interface

By virtue of the complementary comparative advantages between Israeli and Korean innovation, great commercial potential exists at the point of interface between the two countries. Koreans are interested in investing in advanced technological developments and are constantly searching for innovative components that can be integrated into their products. Israeli entrepreneurs are also interested in technological development but additionally seek manufacturing and Scale Up opportunities that the Koreans can provide. The combination of capabilities enables the development of advanced final products and their introduction into global markets.

Two projects in which the Israeli company Sightic VisaSightic Visa was acquired by Broadcom in 2010. participated and that were authorized and supported by the Koril Foundation, illustrate the value in the integration of the two countries’ comparative advantages. The company, specializing in the development of advanced chips for use in cameras, developed, within the framework of two separate collaborations, advanced components for the security division of Samsung of that period, Samsung Techwin, and for LGE, that were intended for integration in security and surveillance cameras produced by the Korean conglomerates.

The Korean conglomerates are even forging a presence in the Israeli innovation system via local R&D activity and direct investment in Israeli technologies. Samsung operates a R&D center in Israel that employs approximately 200 workers. The center was established in 2007 following the purchase of the Israeli company ‘Transchip’ that developed chips for cellular cameras. Additionally, Samsung invests in Israeli startup enterprises through its own investment channels – Samsung Venture Investment Corporation (SVIC) and Samsung Catalyst; via the innovation program Samsung NEXT Tel Aviv; and the accelerator program Samsung Runway, that invest in early stages technology companies. The LGE division of LG Corporation also operates an R&D center in Israel, the focus of which is identifying Israeli technologies capable of integrating in the company’s products, and development of collaborations with the Israeli companies behind them.

The fields of academic research also possess tremendous advantages for collaboration between Korea and Israel. Korea leads the way in applied research that complements the basic Israeli research: Most Korean government ministries have several affiliated Public Research Institutes, while in Israel there is a small number of such institutes.

The Koreans bring additional important attributes to these collaborations: exemplary implementation capability, meeting deadlines, high quality service, support of minute details and an impressive reputation. Israelis, as described above, bring pioneering technologies, audacity and the appetite for risk – understanding that innovation contains no certainty of success.

The Challenges of Mutual Relations

The differences between the business approaches and accepted norms of behavior in Israel and Korea also create challenges for the realization of the potential of cooperation. The differences in the perception of innovation itself, although standing at the foundation of the synergy, may also prove to be an inhibiting factor. While Israelis understand that innovation is by definition experimental and involves risks and frequent changes, Koreans hesitate before committing to a project the success of which is uncertain, and might show low flexibility to changes required during the process of technological development.

Language differences might influence the quality of communication during collaborations. This challenge illustrates the significance of direct communication between the partners: a practical demonstration during the development process communicates technical knowledge between professionals even without words.

Different organizational culture between Israeli companies and their Korean counterparts also creates challenges for entrepreneurs interested in cooperating with each other. For example, Israeli companies are characterized by a relatively flat organizational structure and relatively open communication between junior staff and management. In Korea however, companies are characterized by more rigidly hierarchical structure that also leads to lengthy bureaucratic processes such as receiving the necessary authorizations to start a project.

Additionally, in Korea and in other eastern Asian countries, an alcohol-filled night outing with colleagues and clients at the company’s expense (termed Hoesik) is one of the keys to conducting business. This is not practiced in Israel, where socializing – including business – is frequently done in a family setting.

Naturally, it is recommended that professionals from both countries seeking to cooperate be attentive to cultural nuances such as these different local business customs, different national holidays and other situations that may pose challenges to ongoing communication.

Routine business analyses are therefore not sufficient as preparation for the creation of collaborations with companies in both countries, and significant importance should be accorded to familiarization with both cultures, particularly common business culture. In this context, the KORIL Foundation serves as a knowledge bank and acts to bridge gaps in business culture and enable effective communication between the collaborating parties.

Upcoming Objectives: Agro-Technology and the “Civilianization” of Defense Technologies

The KORIL Foundation constantly explores new directions for cooperation between Israel and Korea. As is to be expected, KORIL invests in sectors in which both economies excel, such as ICT and electronics. In recent years considerable interest has developed in applying “smart” technologies agriculture (agro-technology), robotics, in disaster management and others. As a result of experience in contending with terror attacks and military conflicts, Israel has acquired expertise in emergency healthcare and first responders’ technologies. This experience is relevant to the Koreans who in recent years have contended with civilian disasters in the construction and maritime sectors. In the robotics sectors, a large study is being conducted in both countries towards the end goal of a joint disruptive technological breakthrough.

We wish to thank Dr. Ira Lyan for her contribution to this chapter.

- The characterization and comparison of cultures in different countries may be inclined towards generalization. Any error on our part regarding cultural nuances in Israel and Korea is unintentional.

- Yim, D. S. (2004). Korea’s National Innovation System and the Science and Technology Policy. Seoul: STEPI; ↩︎

- OECD figures – GDP in current prices. See: https://data.oecd.org/gdp/gross-domestic-product-gdp.htm ↩︎