The Israeli high-tech industry is at the forefront of Israeli innovation and its achievements set new records every year. Nevertheless, as far as gender equality is concerned, Israeli high-tech has significant room for improvement. Women comprise only one third of Israeli high-tech employees, a figure that has remained constant over time. At each stage of the path to the high-tech industry and subsequently, within the industry itself, women are a distinct minority. The higher up one examines the ladder of seniority, the lower the ratio of women startup founders, or partners in venture capital funds – portraying a discouraging reality. Global comparisons with other international centers of innovation show that Israel lags behind other countries with low levels of women entrepreneurs and funding of their companies. Initial encouraging signs have been witnessed in recent years with increased numbers of women signing up for academic studies in high-tech professions, an increase in the number of female highschool students graduating with matriculation certificates in computer studies, and in other indices, but progress is slow. Processes must be accelerated to reduce the gender disparity while increasing joint efforts of government and the high-tech industry itself at each stage.

This report, being published for the first time, aims to lay the foundations of a knowledge infrastructure that is based on facts and figures in order to gain a deep understanding of the reality for women in Israeli high-tech and in the paths leading to it. Furthermore, considering the important role of technological innovation within the Israeli innovation ecosystem, this report places special emphasis on analyzing the gender aspects of the Israeli startup arenas, including reference to the ratio of women entrepreneurs, the sectors in which they choose to establish companies, and their ratio in funding rounds. It is specifically in light of the impressive flourishing of Israeli high-tech and the significant levels of capital it has attracted in recent years, that it is important to highlight this weaker angle of Israeli high-tech.

What is the Path that Leads Women to High-Tech?

Women’s path to the high-tech sector begins at an early stage. Choices made by high school students have a significant influence on their later professional career and on their chances of being accepted to the field. For women to become entrepreneurs, to serve in senior corporate roles, or to progress to investment roles in venture capital funds, they must first acquire relevant education and training and advance within the industry. To increase the representation of women in the industry it is therefore important to increase their relative presence at each stage on the path that leads to high-tech.

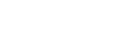

The beginning of this path – the 5-study unit matriculation exams in mathematics – is characterized by a state of near gender equality. The gender gap begins to widen however during the following years of military service in the development and cyber units that pave the way of those serving in them to the Israeli innovation sector. Women comprise 23% of the soldiers serving in these units. The situation is slightly better in academic high-tech studies where, although the number of female students increased by 64% within the last decade, their relative share of total students in these subjects has increased only slightly and women still comprise less than one third of the total number of students. Subsequently, and as the level of seniority rises, the ratio of women in high-tech industry steadily declines.

The worst situation in the high-tech sector from a gender perspective is that of startup entrepreneurs who constitute the spearhead of Israeli innovation. The present startup generation – that develop groundbreaking solutions, quickly forge their way forward, and compete in the global arena – determine the future of Israeli high-tech. Some of them become large mature companies employing large numbers of workers, some will be bought by multinational corporations that will use them to establish R&D centers in Israel, and some will close, but the technological, professional, business, and managerial knowledge they accumulate will filter down to other places in the Israeli innovation ecosystem.

The human makeup of the people leading these startups who will influence the direction of Israeli high-tech is thus of great importance. In this report, we focus on the gender aspects of Israeli technological entrepreneurship out of an understanding that women entrepreneurs who establish startups recruit more female employees to their companies and promote more women to senior executive positions.1 Studies even show that founding teams with greater gender diversity are more innovative and raise more funding.2 Increasing the number of women entrepreneurs will therefore have a positive influence in improving the gender inequality that currently characterizes Israeli high-tech.

The bottom line is a somber one: the ratio of Israeli women entrepreneurs in no way corresponds to their percentage of the general population. Women are CEOs of only 9.4% of all startups founded in Israel over the past decade. When examining the total capital invested in Israeli startups, the ratio of women is even lower: only 4.4% of total investments. Of the partners in Israeli venture capital funds, only 16% are women and of these, an even lower percentage serve in investment roles. Women take almost no part in leading the generation of Israeli companies that has grown locally. A sample of Israeli technology companies that executed IPOs during 2020-2021 as well as veteran Israeli public technology companies that employ over 1,000 workers, showed that women occupy only 22.6% of the managerial positions.

The goal of this report is to shed light on the state of women in Israeli entrepreneurship using up-to-date data that has been analyzed and published by the Innovation Authority for the first time. The insights arising from the data will ultimately enable the formulation of programs pertaining to the private and government sectors, however Israeli high-tech companies and investment funds can already take immediate short-term measures to improve their own situation in this regard.

Improving the level of gender equality in Israeli technology entrepreneurial activity will lead to greater diversity in Israeli high-tech through the input of new ideas, varied styles of management, and a broader entrepreneurial viewpoint. In a reality whereby the Israeli hightech market suffers from a chronic shortage of workers and where women are a minority of all Israeli high-tech employees and of the students in the relevant academic study courses, the cultivation of new role models of women CEOs and entrepreneurs to lead these companies is important, both for their influence on the environment and for encouraging more women to enter this field. Furthermore, founding teams made up of more women generally create companies around them with more diverse human capital. In the long-term, this may also exert a positive influence on reducing the general economic-social gender inequality in Israel.

Situation Report: On the Way to High-Tech and Startups – Where are the Women?

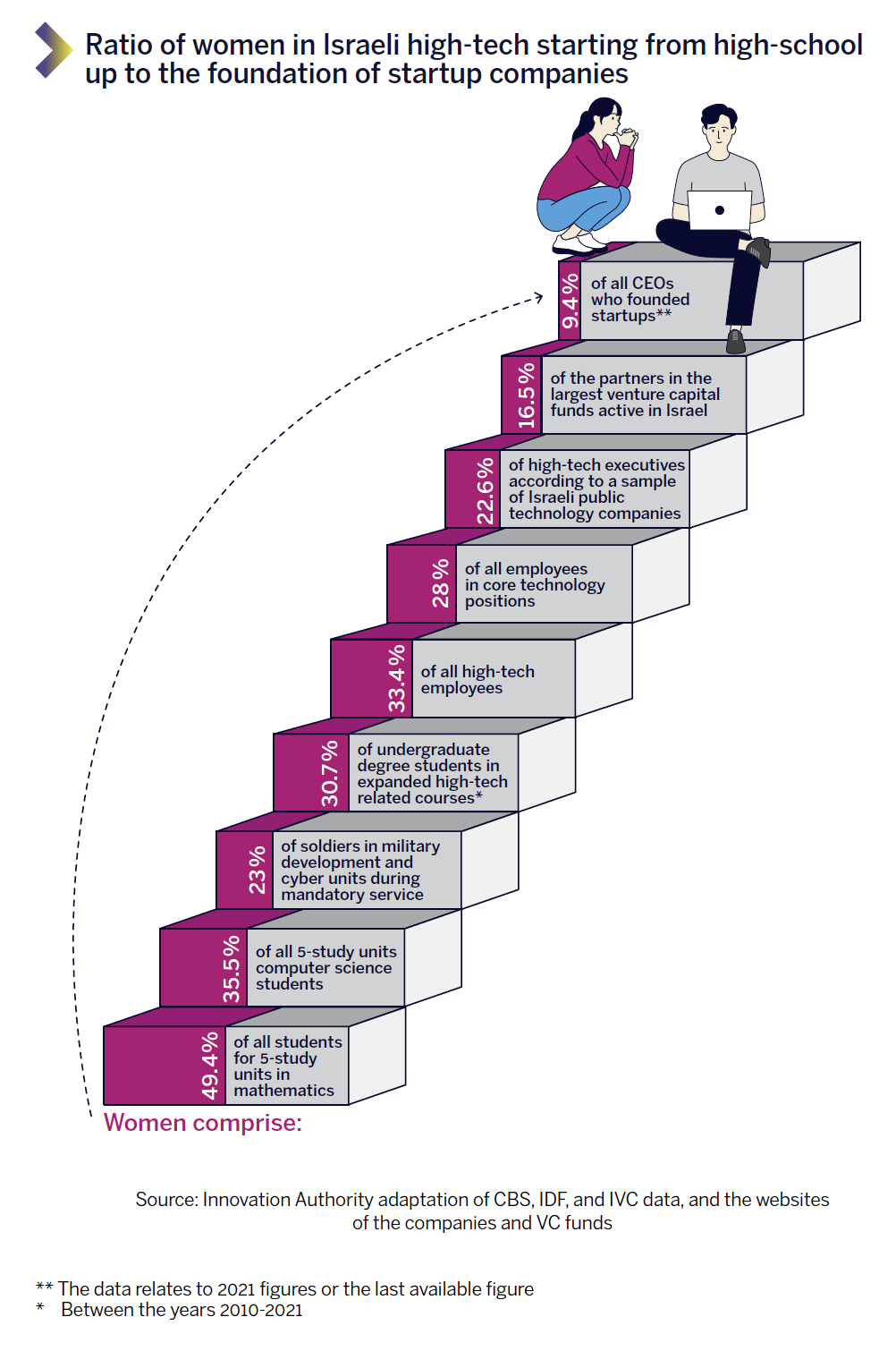

1. High-School: Only 35% of those taking 5-study units computer science matriculation exams are women

The picture at the beginning of the road to high-tech seems encouraging: In 2020, almost half (49.4%) of all the students taking the 5-study unit matriculation exam in mathematics were women – approximately 9,000 female students. The disparity between the ratios of male and female students taking the exam narrowed from a situation where 6,100 of all students taking this matriculation exam in 2016 were women (47.6%). In the Arab sector, the ratio of female students taking the 5-study unit mathematics exam is significantly higher – 64.3% of all the students taking the exam. In general, between 2016-2020, the ratio of students taking the 5-study unit mathematics matriculation exam out of the total number of students (Jews and Arabs) during that period rose from 13% to 16.9% i.e., the number of female students taking the exam increased by 1.5 (time and a half) during this period.

The subjects chosen by students at this stage of their lives influence the fields they will study later in life. According to the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS),3 30% of the female students who are eligible for a matriculation certificate in science-oriented subjects (primarily mathematics and the sciences)4 continue to an academic degree in a STEM study course.5 The parallel figure for male students stands at 48%. The chance that a female student who did not graduate with a science-oriented matriculation certificate will choose to study for a STEM subject academic degree is only 5% (compared to 13% for male students).

In other words, the tendency of female students who graduate with a matriculation certificate in math- and science-oriented subjects to continue to undergraduate academic studies in STEM subjects is six times higher than female students graduating with a matriculation certificate in other subjects (among male students, this tendency is 3.7 times higher). The significance of this is that female students’ choice of study subjects at high school has a much more critical influence on their subsequent career choices than those of male students. Female students choosing not to study mathematics or science in high school will probably also not go on to study them later. Data shows that even when female students do choose to study these subjects at high school level, the chance that they will later study high-tech subjects is lower than that of male students. The chance of a male student who studied for a math- and science-oriented high school matriculation certificate to go on to study STEM subjects at university is 60% higher than that of a female student in the same study course.

Female students’ choice consequently impacts the gender balance of the potential future high-tech workforce. An examination of the ratio of female high school students taking 5-study unit matriculation exams in computer science reveals a significant disparity in comparison with the ratio of male students choosing this subject: only 35.5% of those taking the exam are women (approx. 3,500 students). This ratio has increased from 31.7% in 2016. Further examination of the data shows that 14.8% of the male students in the Jewish education system in 2020 took the 5-study unit exam in computer science compared to only 6.1% of the female students.

2. Military Service: Female Soldiers Fill Only 13% of the Military’s Cyber Roles

Military service in a technology unit is a springboard for the sought-after entry into the high-tech industry. These units grant those serving in them professional training, experience, and a network of contacts with other graduates of the unit. The importance of service in the military’s technology units cannot be underestimated and a recent survey conducted by the Aaron Institute for Economic Policy at Reichman University found that 47% of the employees in developmental positions in growth companies have a technology background acquired during their military service.6

Nevertheless, the ratio of women serving in technology positions has remained low and almost unchanged. 31% of those serving in the military’s computer and software roles in 2019 were women.7 However, the ratio of women in mandatory military service serving in core technology roles – development and cyber – was only 23% of all those serving in these roles. In practice, therefore, the ratio of female soldiers in the military’s core technology roles is lower than their ratio in the high-tech industry. IDF figures show that the ratio of women soldiers serving in cyber roles in 2019 was just 13%.8

Among those serving in the Academic Reserve (Atuda) programs, the picture is a bleak one: only 15% of all the students in the engineering and exact sciences courses (that comprise 75% of all those serving in the IDF Academic Reserve) are women.9

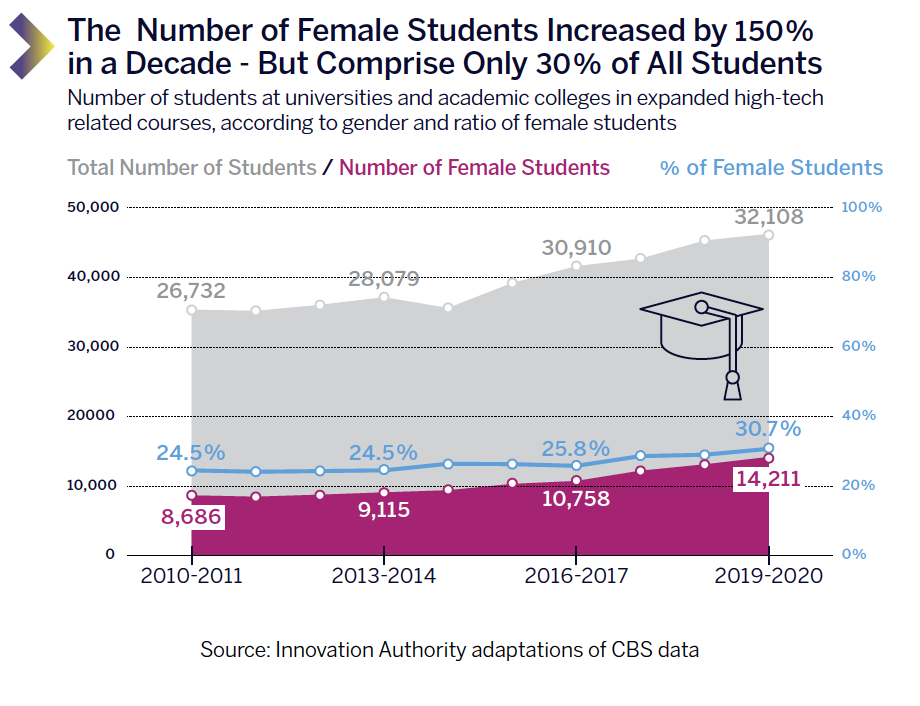

3. Academia: The Number of Female Students in High-Tech Subjects Has Increased by 64% in a Decade – But They Still Comprise Less Than One Third of All Students

The universities and academic colleges are important stations on women’s path to hightech. The encouraging trend of the past decade is that, according to the CBS, the number of women students studying for an undergraduate degree in expanded high-tech related courses at universities and academic colleges rose by 64% – from 8,686 in the 2010-2011 academic year to 14,211 in the 2019-2020 academic year. Undergraduates are a significant cadre of potential (as far as their number is concerned) for integrating into the hightech industry upon completion of their academic studies. The growth in the number of male students in expanded high-tech related courses is slower – and the number of male students rose by 1.2% during the same period. Despite the encouraging trend, female students comprised only 7.3% of all students in undergraduate degrees in expanded high-tech related courses. The number of male students during the same academic year stood at 32,108.

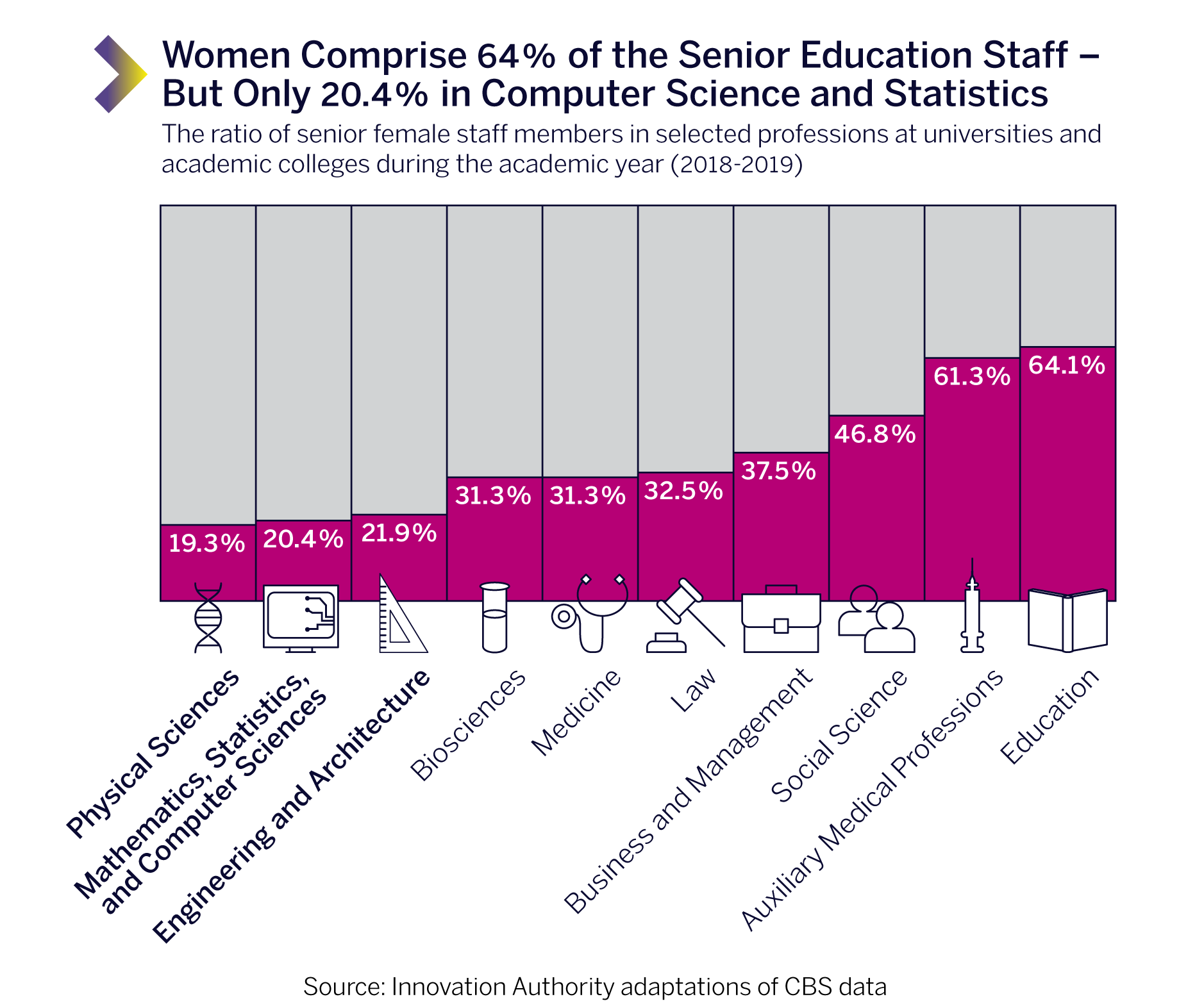

When examining the senior academic staff – those training the future generation of hightech professionals and serving as their role model – at faculties and schools for the relevant subjects, the reality is no more positive. In the 2018-2019 academic year, the ratio of senior female staff members stood at 19.3% in the field of physical sciences, and at 20.4% in the fields of mathematics, statistics, and computer science.10 In engineering and architecture courses, the ratio of senior female staff members was 21.9%. The representation of women on the senior staff of departments, the graduates of which generally integrate into the high-tech industry, is significantly lower than that of other departments where the rate of women’s employment is higher. For example, in medicine, the ratio stands at 31.3%, social sciences 46.8%, medical auxiliary professions 61.3%, and education 64.1%.

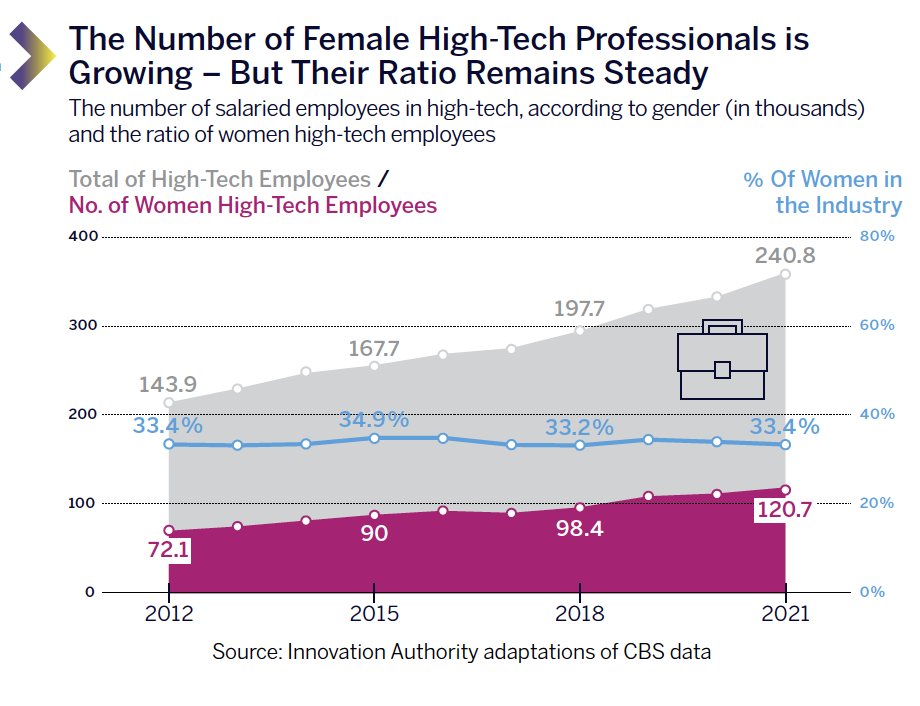

4. The High-Tech Industry: One Third of the Employees are Women – Only 22.6% of Senior Executives are Women

According to CBS data, the total number of 361,500 high-tech employees in 2021 consisted of 120,700 women and 240,800 men.11 The ratio of women employed in high-tech has remained almost unchanged at about one third of the salaried high-tech employees for at least the last three decades. In 2021, the ratio of women in the industry, including core technology and other roles (such as marketing, sales, human resources etc.), stood at 33.4% – a ratio that reflects a decline of 0.6% compared to 2020.

The growth rate in the number of men employed in high-tech in 2021 was 50% higher than that of women – the number of women in the industry grew by 6% compared to an increase of 9% in the number of men. In 2020 too, the year in which the Covid pandemic broke out with numerous lockdowns and disrupted activity of the education system that primarily affected working women, there was a disparity of 80% in the rate of men joining the high-tech industry compared to that of women (5% and 2.8%, respectively). Analysis of the multi-year average of the period between 2013-2021 shows that the average yearly growth rate in the number of women and men in the high-tech industry is almost identical and stands at 6%. Nevertheless, when comparing the growth in the number of women and men in high-tech in 2021 to that of the other sectors of the economy, the growth in hightech is significantly higher. The economy’s general growth rate in 2021 was 1.1% among men and 2.4 among women.

The ratio of women employed in core technology jobs fluctuates slightly more but also maintains a level of 26%-28% of total employees in these positions between 2012-2019 (according to the last available figure from the CBS). The ratio of women employees in technology roles is largely influenced by the rate of women graduates from the military’s technology units and high-tech subjects in academia. Until these ratios increase significantly, it is reasonable to assume that there will be no fundamental change in the gender makeup of technology jobs in high-tech.

One of the most significant indices in measuring gender equality in high-tech is the ratio of women that occupy senior executive positions. The number of senior women executives influences women’s potential to progress to technology entrepreneurship and to other key positions and influential roles in the Israeli innovation ecosystem. To assess the state of Israeli high-tech, we conducted an examination of the number of women in senior executive roles in a sample of mature Israeli technology companies that includes companies that conducted IPOs relatively recently and veteran Israeli public technology companies. Later in the report, we discuss in-depth the state of women in startup entrepreneurship while the state of executives in this sample group relates to the state of women in advanced-stage companies.

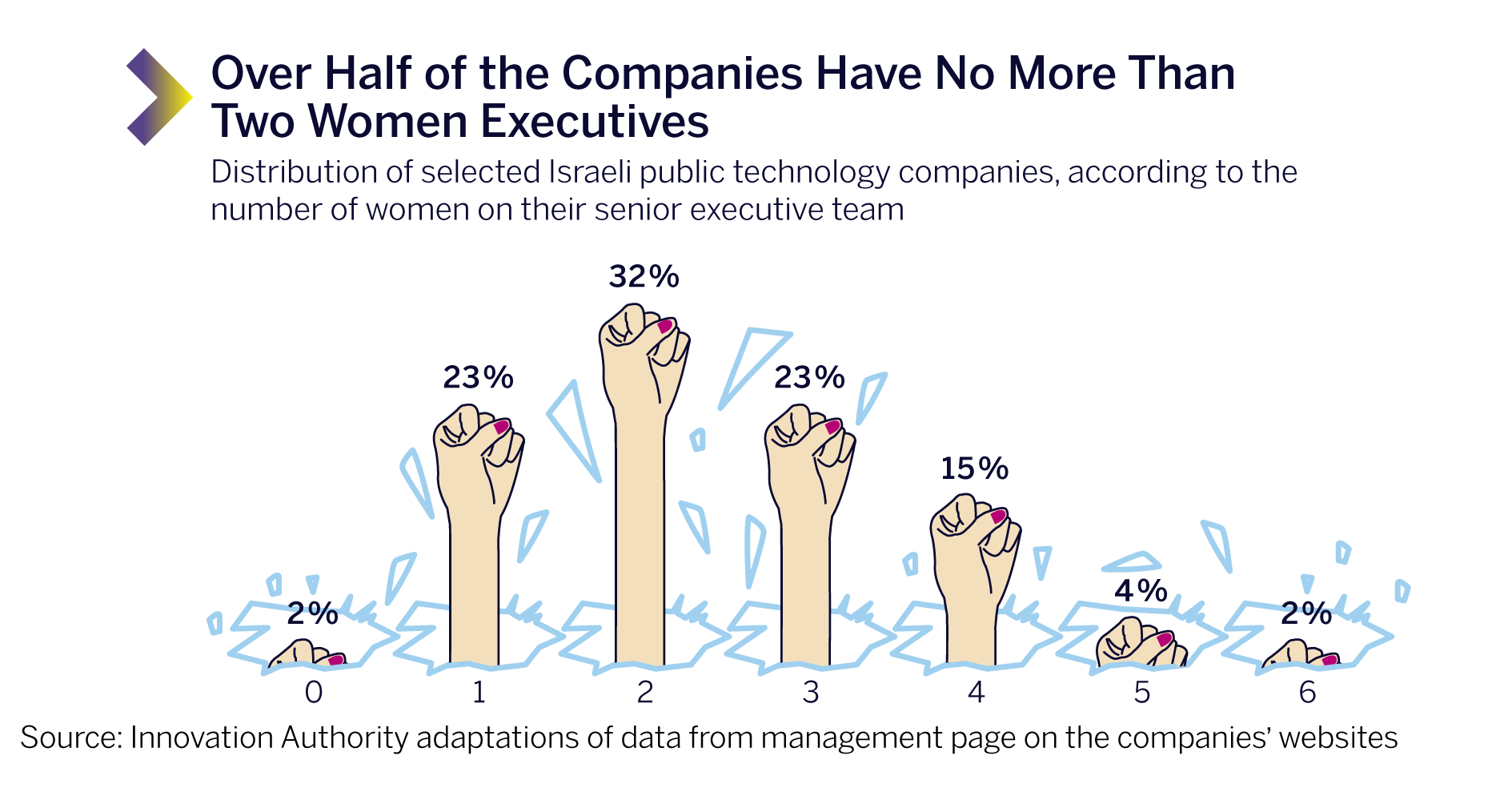

Unsurprisingly, the executive teams of mature Israeli technology companies in no way reflect gender equality. Although only one company out of those sampled had no women on its executive team, 23% of the companies had only one woman in an executive role. In 79% of the companies there are no more than three women on the senior executive staff. In total, of the 575 senior executives in the technology companies examined, only 130 (22.6%) are women.

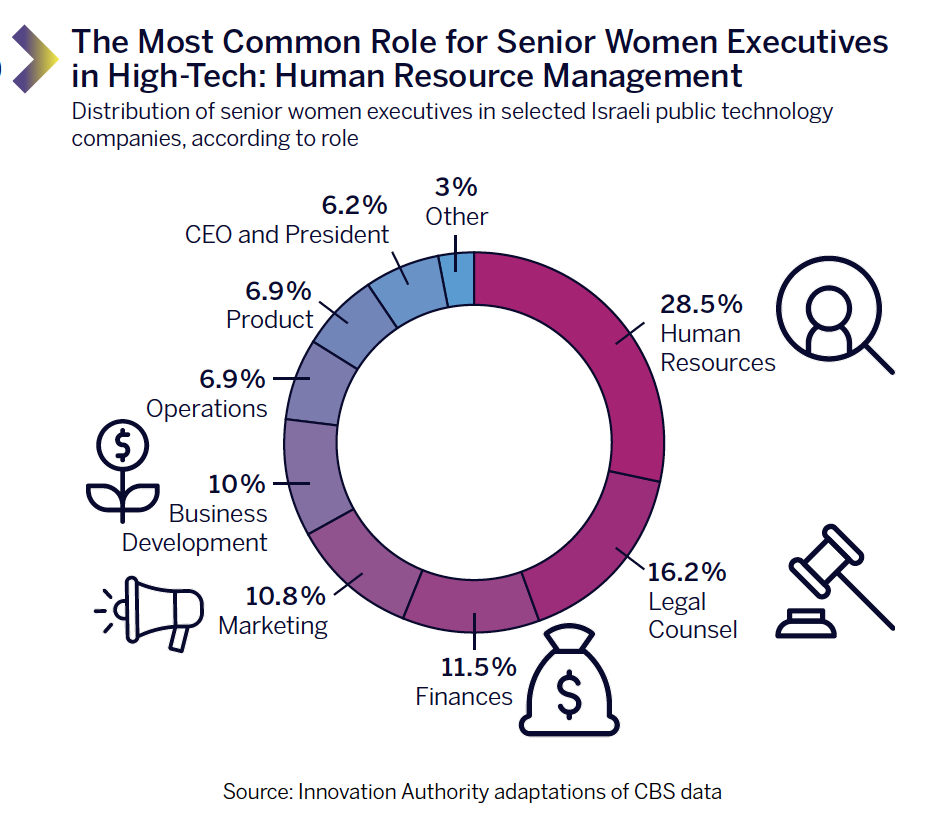

There is great importance to the types of roles filled by the senior women executives. The figures show that 28.5% of the female executives in the sample work in human resource management i.e., compared to other roles, the lion’s share of senior women figures in Israeli high-tech work in this field. In one third of the companies with only one female senior executive, this woman works in human resource management. In other words, beyond the fact that women are under-represented in high-tech, and especially in senior executive roles, when they do occupy such positions, these are generally the less well-paid jobs.12

The next most common areas for women executives in the sample are legal counsel (16.2% of the senior women executives) and finances (11.5%). Other relatively common areas among senior women executives are marketing, business development, and operations. 6.9% of the senior women executives occupy a product manager role which falls under the field of technological development but among the companies sampled there was not even one woman designated as CTO or VP R&D. 6.2% of the senior women executives are CEOs or company presidents.

The survey was conducted in February 2022 and included 53 mature Israeli technology companies. Of these, 24 are public Israeli technology companies that employ more than one thousand workers and 29 are relatively young public technology companies that held an IPO in the last two years. The survey measured the number of senior men and women who appear on the companies’ websites.13