Israeli High-Tech: Where is it Headed and How Will it Affect the Israeli Economy?

As shown above, Israeli high-tech has grown significantly over the past decade. The sector has established itself as the economy’s shock absorber, especially during crisis periods, and has accounted for high proportions of the growth in Israeli GDP. Furthermore, it is clear that high-tech’s contribution to GDP and the economy stems primarily from the sector’s employees.

Investments in startups reached a peak in 2022. Since then, they have been in a downward trend which appears, as of now, to have been curbed. A similar negative trend characterized the indices relating to the number of available jobs in the sector. In other words, the heights of 2021-2022 were the exceptions and Israeli high-tech appears to have returned to the long-term trends that characterized it during the years that preceded this growth.

This situation touches on a series of issues relating to the trends that will characterize Israeli high-tech in the coming years, and how these trends will impact the growth of the Israeli economy in general. These issues will be discussed in this section of the report.

The central issues concerning Israeli high-tech:

Issue No. 1: High-Tech’s Centrality to the Economy and the Impact of Changes in the Sector on the Economy

As presented in the first section of this report, Israeli high-tech constitutes a central factor in the Israeli economy, and its share in the various economic indices has been gradually increasing in recent years. Moreover, the human resource is the primary reason for the sector’s growth in Israel. In other words, in economic terms, the high-tech sector’s human capital is Israel’s “natural resource”.

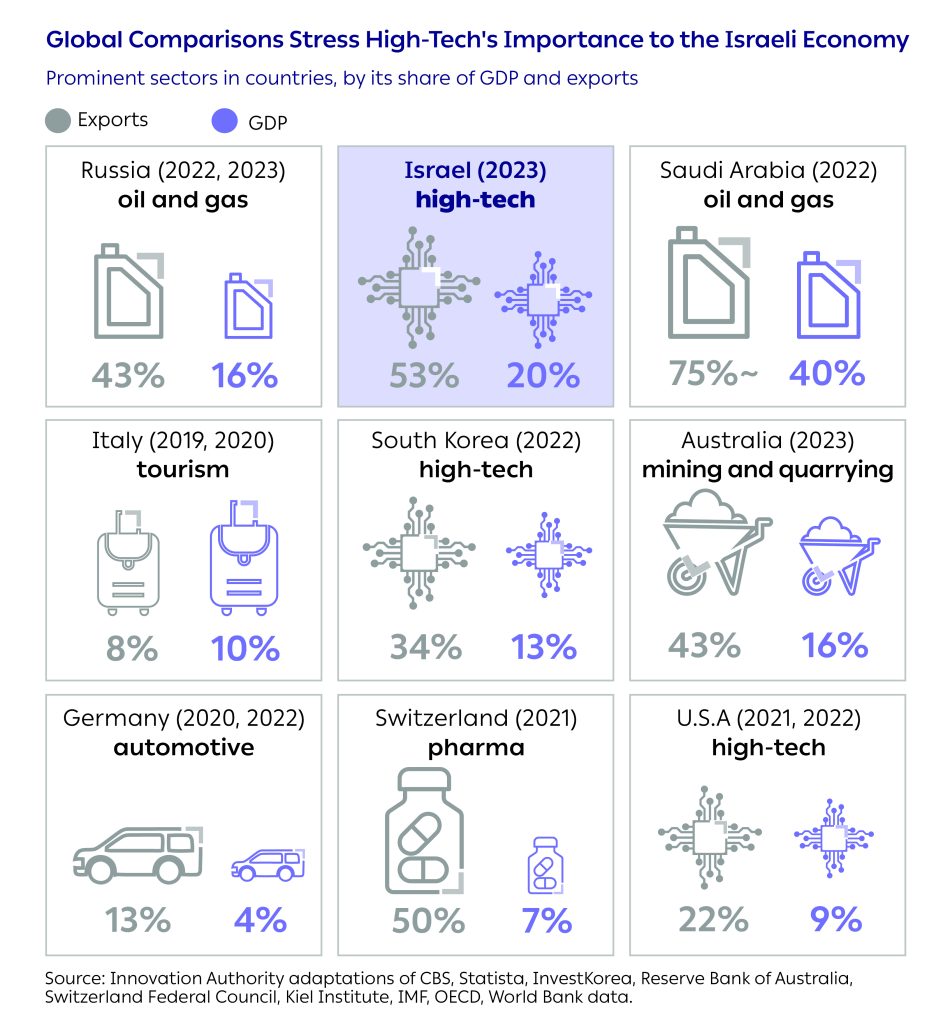

From a global perspective, high-tech’s centrality in the Israeli economy is a unique phenomenon. Its share of Israeli GDP – approx. 20% – is similar to that of natural minerals such as oil and gas in the economies of those countries that rely on them. High-tech’s share of Israel’s exports is also high and stands at more than 50% in recent years. In South Korea, for example, a country in which, like Israel, the investment in R&D as a ratio of GDP is extremely high, the high-tech sector accounts for 13% of GDP and a third of total exports. In the US, the home of the world’s leading technology hubs, the high-tech sector contributed less than 9% of GDP in 2022 and less than a quarter of total exports in 2021.

Considering the centrality of high-tech, changes in the sector may influence the entire economy. Like other countries where a specific sector is of strategic importance, Israel should also have an organized long-term policy for the sector that incorporates relevant risk management.

The State’s Role in Accelerating High-Tech

The State’s Role in Accelerating High-Tech

The transformation of high-tech into a significant sector of the Israeli economy – in terms of its share of GDP, exports, employees, and tax payments – highlights the possibility that changes in this sector can affect the entire Israeli economy. This raises the question of how the State of Israel should support the sector on the one hand while managing the risk that may arise in the event of major changes affecting it.

As of today, implementation of state policy regarding the high-tech sector has been expressed via direct financing of companies, primarily by the Innovation Authority and the DDR&D; funding the establishment of R&D infrastructures; tax benefits for investors and companies, and attempts to accelerate the increase in personnel with the skills necessary to work in high-tech, mainly through multi-year programs of the PBC-CHE and as part of implementing the Perlmutter Committee’s recommendations.

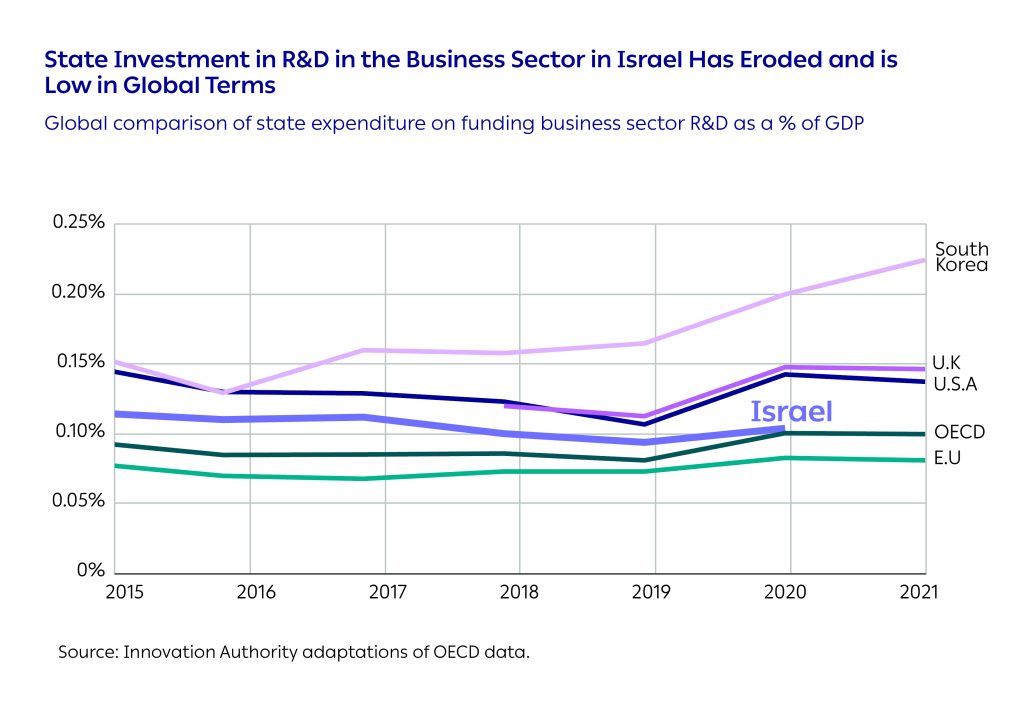

An international comparison shows that in Israel, the state’s share of funding R&D activity in the business sector in terms of a percentage of GDP, is similar to the OECD average but significantly lower than countries considered to be global innovation leaders such as the US, Korea and the UK.

The State of Israel, as a years-long world leader in terms of investment in R&D as a percentage of GDP (over 6% of GDP), cannot afford to be satisfied merely with a level similar to the OECD average in a sector of such strategic national economic importance.

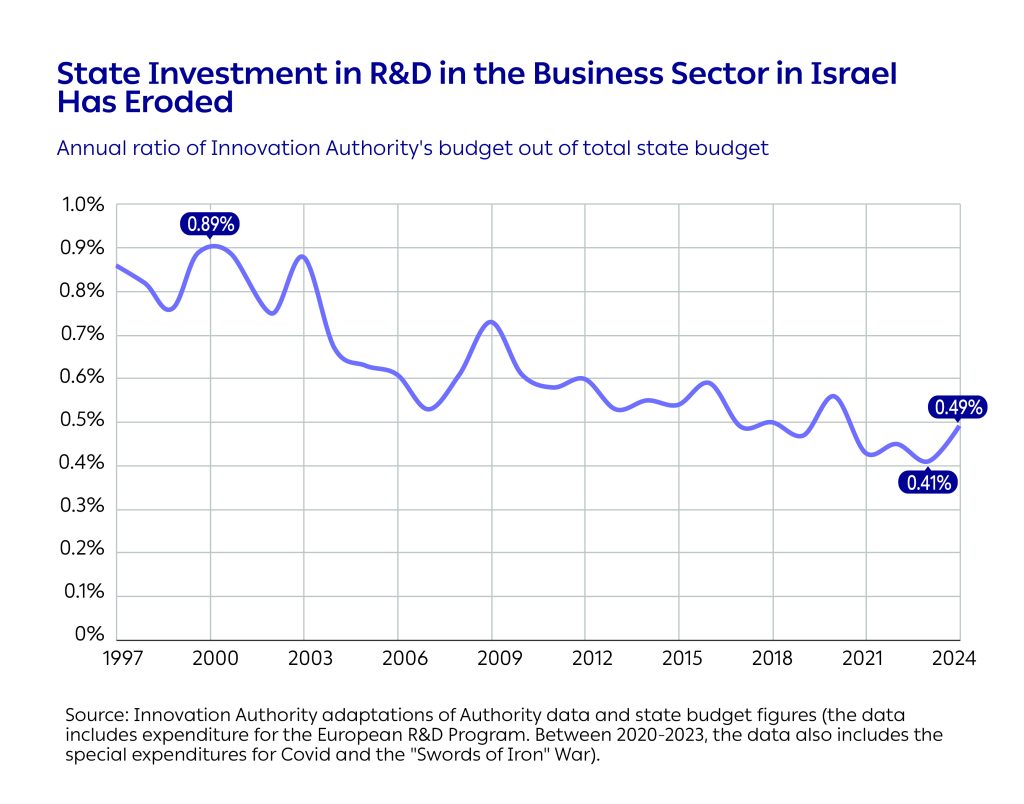

Furthermore, it is customary to relate to the state budget as an expression of national economic and social priorities. An examination of the Innovation Authority, the state entity responsible for advancing the Israeli high-tech industry, shows that the share of its budget out of the total state budget has consistently eroded over the past twenty years. The Authority’s budget has declined by half from approximately 0.9% of the total state budget in 2000 to only 0.41% in 2023. Over a period of more than twenty years, the Authority’s budget grew from 1.6 billion shekels to just 2 billion shekels in 2023, with the entire growth being explained by an increase in state expenditure in lieu of participation in the European R&D Horizon Europe Program. At the same time, the total state budget increased from 180 billion shekels to almost half a trillion shekels.

In 2024, the Innovation Authority’s budget was increased by nearly 1 billion shekels in relation to 2023 with the aim of providing a response to the turmoil experienced by Israeli high-tech.1Details of the various programs operated by the Authority during 2023 and 2024 in response to the war are presented at the end of this report In light of the high-tech sector’s size, this issue should possibly be given greater weight on a permanent basis when determining state priorities.

The Innovation Authority believes that the government should strive to increase certainty for all the multinational entities involved in Israeli high-tech. One of the ways to increase certainty is by creating a multi-year plan for state investment in high-tech. Considering the expected influences of the war on the Israeli economy, and the expected need to tighten the belt on government expenditure, the creation of government commitment to the success of Israeli high-tech may send a positive signal to the market.

Issue No. 2: Creating Inclusive Growth by Expanding the Circles of Technology Employment

One of the central questions facing Israel is how to expand high-tech’s success to the other sectors of the economy and create inclusive growth. Currently, a gap exists between high-tech and other sectors, expressed among others in the high salaries and productivity that characterize high-tech compared to the other sectors.

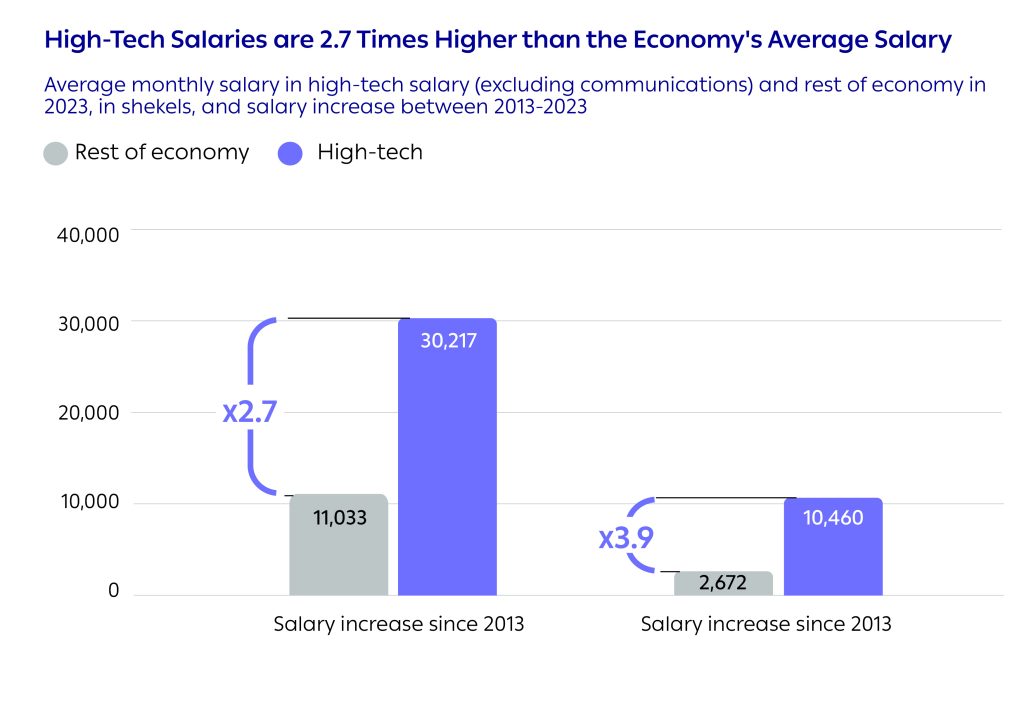

In the meantime, the gap between the average salary in high-tech and the rest of the economy continues to grow as can be seen in recent decades. The average monthly salary in high-tech in 2023 was 2.74 times higher on average than the rest of the economy and stood at 30,217 shekels. In January-February 2024, the average monthly salary in high-tech rose to 32,691 shekels. This figure may be updated as it includes bonuses that are generally awarded at the beginning of the year.

Even in 2023, that was characterized as a slower year in a range of indices, hightech salaries continued to increase and rose by almost 2,000 shekels a month – an increase of 7%. In the rest of the economy, the average monthly salary rose by 600 shekels in 2023, an increase of 6%.

Broadly speaking, between 2013-2023, the average monthly salary in hightech rose by 10,460 shekels, an increase of 53%. In the rest of the economy, the average monthly salary rose by 2,672 shekels during the same period, an increase of 32%.

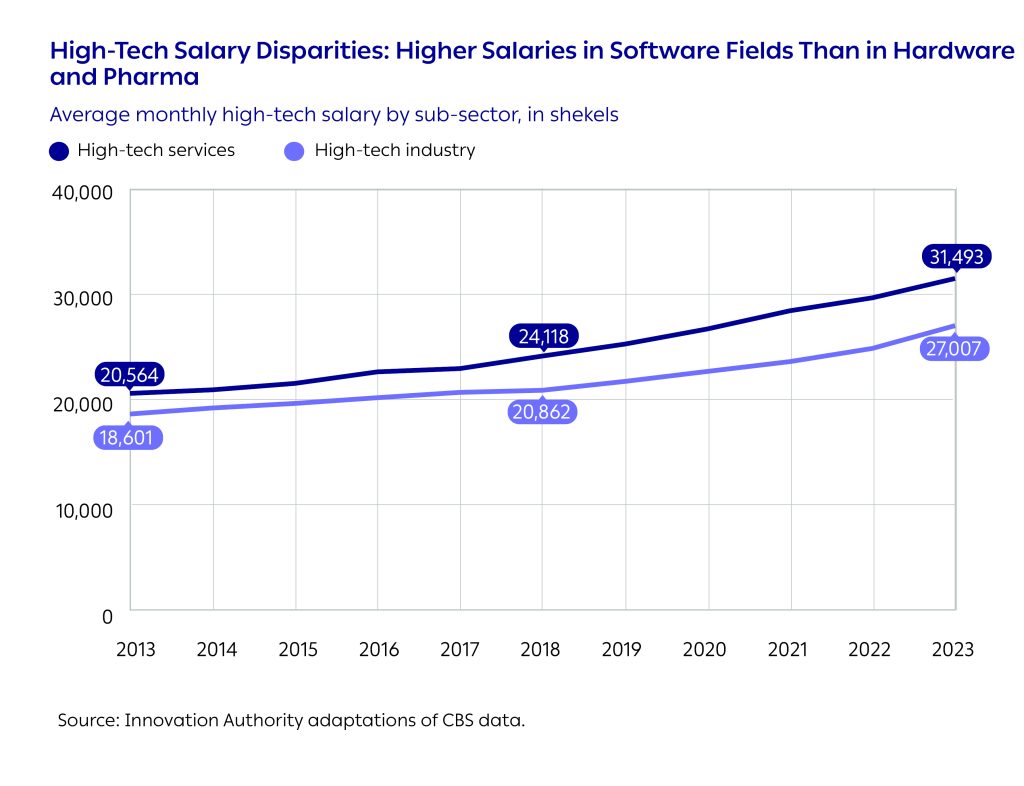

It should be noted that there are salary disparities within the high-tech sector. The average monthly salary in the high-tech services field (software) stood at 31,493 in 2023, compared to 27,007 shekels in the fields of high-tech industry (hardware and pharma). This disparity has grown steadily over the past decade from less than 2,000 shekels a month in 2013 to over 4,000 shekels in 2023.

Introducing Innovation to Other Sectors

Introducing Innovation to Other Sectors

One significant way to expand high-tech’s success and reduce disparities in the economy is the integration of technological professionals in non-high-tech sectors (“tech jobs” as defined by the Perlmutter Committee). The number of workers in technology roles in non-high-tech sectors reflects, among others, the digital transformation they have undergone, the assimilation of innovation, improved productivity, their competitiveness vis-à-vis other companies in the sector, and the introduction of data-based decision-making processes.

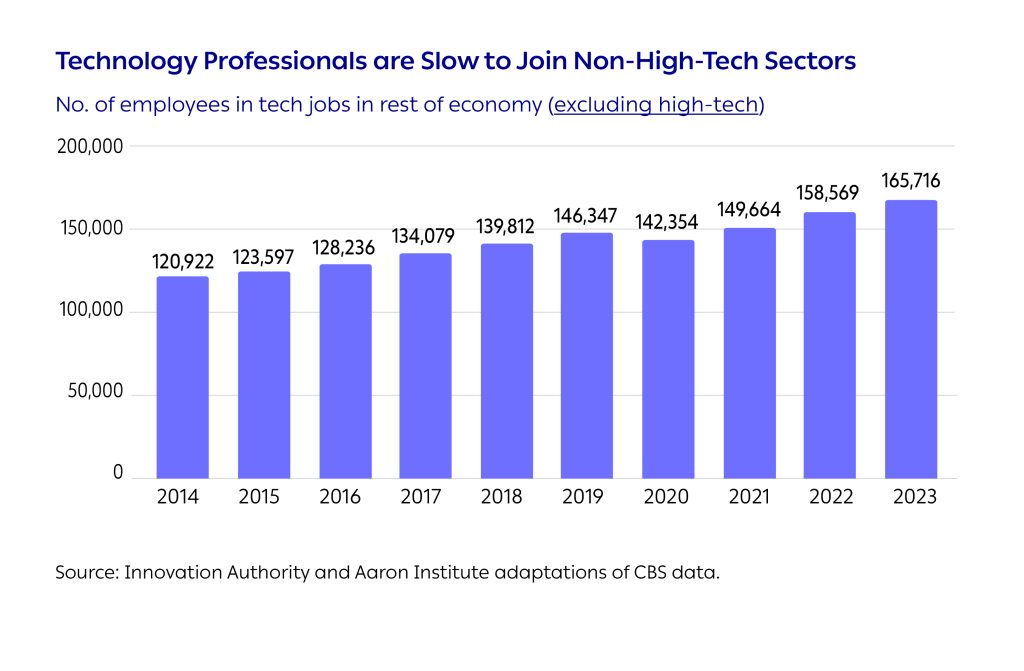

165,700 people were employed in tech jobs outside the high-tech sector in 2023. Over the period of a decade, the number of employees in tech jobs rose by 45,000 jobs. During the same period, the number of employees in technology jobs in the high-tech sector doubled, rising by more than 96,000 employees. In other words, in the non-high-tech sectors, the number of employees in technology jobs grew at a slower rate than that of the high-tech sector. Moreover, the Covid crisis (in 2020) clearly reduced the hiring of workers in technology jobs throughout the rest of the economy and their number declined, while the high-tech sector grew significantly.

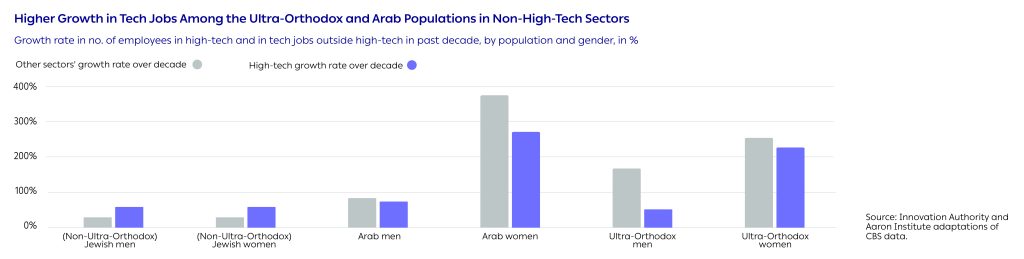

When examining the increase in the number of employees in technology jobs in high-tech and in the rest of the economy by population, it would seem that the technology jobs in the rest of the economy are opportunities for workers from populations under-represented in high-tech to enter high-quality employment and for the creation of inclusive growth. Over the past decade, the growth rates of Arab women, Ultra-Orthodox men, and, to a lesser degree, Ultra-Orthodox women were high in relation to their rate of joining the high-tech sector in the same period.

To reduce the disparities, increase well-being, and enhance the general standard of living in Israel, the state should facilitate and encourage a transition of under-represented populations to tech jobs in the rest of the economy and to the high-tech sector.

We wish to re-emphasize the importance of implementing the recommendations of the Perlmutter Committee to increase the human capital in high-tech and, specifically, the recommendation to invest in high-quality education for all population groups throughout the country with the aim of guaranteeing the long-term prosperity of the high-tech sector and the entire Israeli economy.

Issue No. 3: Competition with Other Global Innovation Hubs

The Israeli innovation industry, that is based on highquality human capital, young startup professionals, and knowledge in unique fields, competes with other hubs of innovation around the world in a variety of areas: human capital and entrepreneurship, funding for investments in startups, and the presence of global technology companies and local mature technology companies. These hubs include “traditional” hubs such as Silicon Valley in the US, but also those that have grown in recent years and established themselves as large and significant hubs such as London. This section will present a picture of Israel’s standing in global comparisons in these fields.

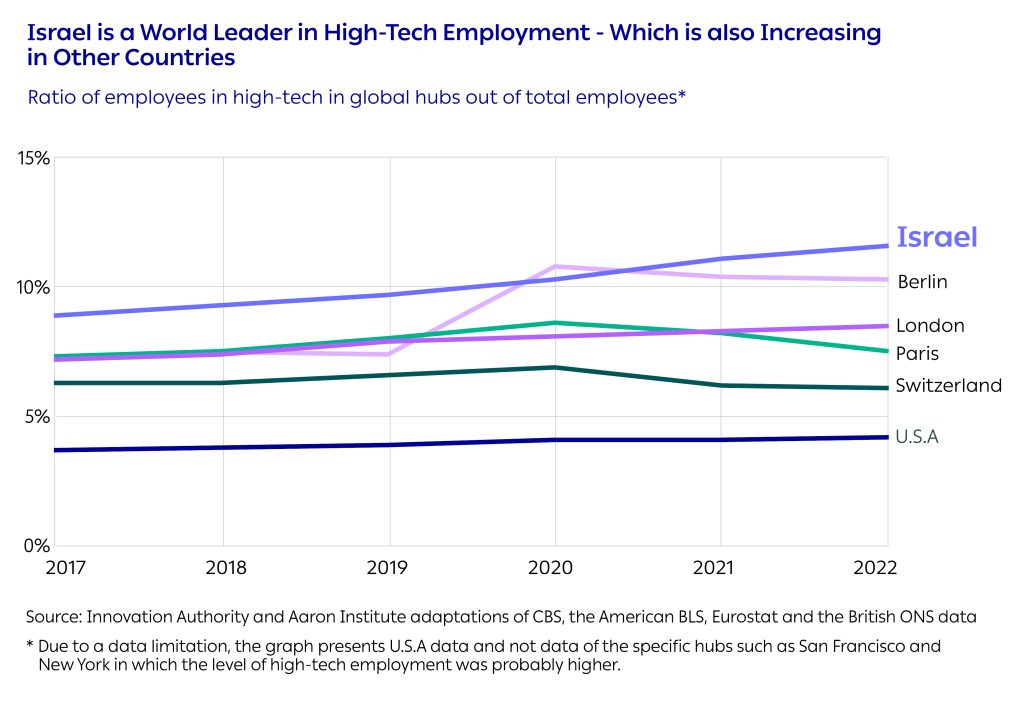

The hubs’ evolvement into innovation leaders is also expressed in terms of employment in professions related to the high-tech sector. In 2023, nearly 12% of the economy’s employees were employed in high-tech – an identical figure to that registered in 2022. In all the hubs examined, the level of employees in high-tech in 2022 was higher than that of 2017. In other words, in all of them, the high-tech sector is growing at a faster rate than the general economy. This testifies to the increasing weight of high-tech in these hubs.

As the ecosystem in these hubs improves and strengthens, so too Israel’s competition in recruiting global resources will increase, primarily in capital and the presence of significant foreign players.

Consequently, increasing high-quality personnel in high-tech is a challenge of national importance. On the one hand, investment and support should be given to quality technology-literate human capital, in accordance with the recommendations of the Perlmutter Committee. At the same time, it is important to prevent the loss of quality personnel to other global innovation hubs, by safeguarding Israel’s standing as an attractive location.

The Competition for Capital: Venture Capital Investments

The Competition for Capital: Venture Capital Investments

The competition between the different hubs is also manifested in the competition for investments in startups, whether direct investments in technology companies or in funds that invest in them. As shown, over the past two years, Israeli startups is experiencing a sharp decline in investments – a sharper decline than in most of the hubs examined.

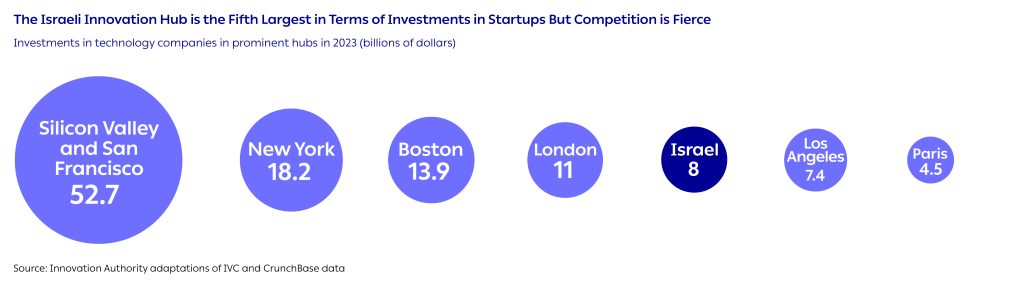

In 2023, Israel was the fifth largest hub in terms of capital raised among the leading innovation and entrepreneurship hubs examined worldwide. The leading hubs are San Francisco, New York, Boston, and London. The funds raised in Israel were similar to Los Angeles.

One of the prominent trends over the past decade is the significant growth of London as an innovation hub. Over the past two years, London has overtaken Israel in terms of investments in startups and is now ranked as one of the world’s five leading hubs.

Fundraising by the local venture capital funds reflects the attractiveness of the hub for investors, especially in early-stage startups.

The investments in startups in Israel are distributed between the local Israeli and foreign venture capital funds. Whereas the mandate of the Israeli funds is to invest primarily in Israel, the investments of the foreign funds are generally split between diverse locations. The capital invested in the Israeli venture capital funds is also largely foreign so, in practice, most of the capital invested in Israeli startups originates from outside the country.

The capital flow to Israel expresses investors’ belief in the local industry. At the same time, the significant reliance of Israeli high-tech on foreign capital compared to other hubs, combined with the distance from the investors, increases the risk that the sources of funding for Israeli high-tech may dry up during times of crisis when investors behave conservatively.

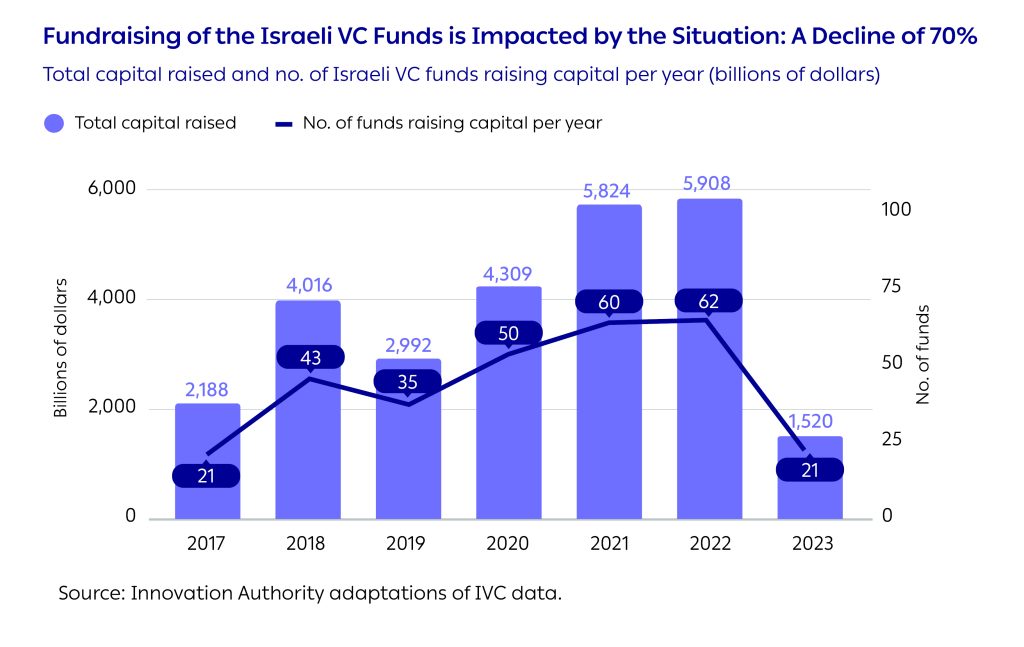

In 2023, the total sum raised by venture capital funds in Israel declined by 75% compared to 2022 and by 67% compared to the average raised in the period between 2018-2022.

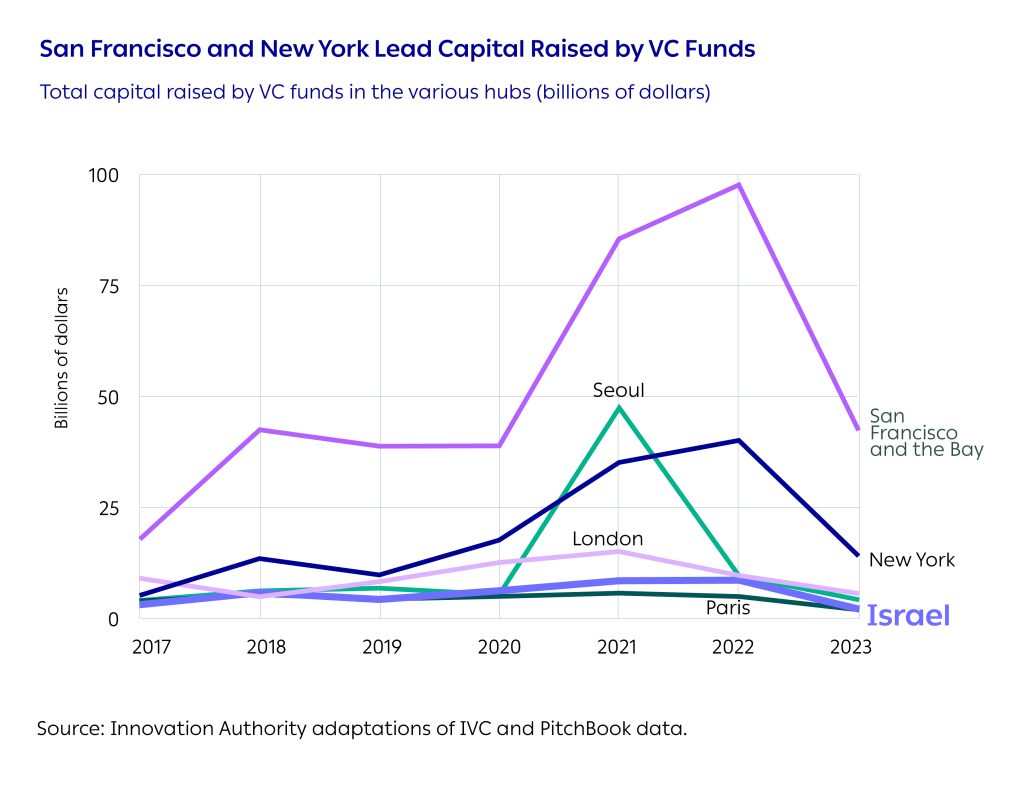

On a global level, most of the capital worldwide is raised for funds in Silicon Valley and, in general, in the American hubs. In 2023, after years during which the total capital raised for the funds increased, fundraising declined. Unlike the decline in startups’ fundraising that began already in 2022, venture capital funds’ fundraising increased that year.

London is an example of Israel’s growing competition. As noted, the total capital raised for technology companies in that hub overtook that in Israel. London also overtook Israel in the venture capital funds segment. Between 2017-2023, a total of 27 billion dollars was raised for Israeli venture capital funds while in London this figure stood at 58 billion dollars.

The decline in the capital raised by venture capital funds in Israel in 2023 was sharper than in other hubs examined. In 2023, the total capital raised by venture capital funds in Israel declined by nearly 70% compared to the average raised between 2018-2022. This compared to a decline of 30%-40% in the other hubs examined. In practice, the capital raised by venture capital funds in Israel declined to a level lower than that of 2015.

The 2008 crisis also had a significant impact on the Israeli funds which failed to raise capital during the subsequent year. This phenomenon was one of the reasons for the launch of the Yozma 2.0 Fund following the events of October 7, in an attempt to prevent a possible shortage of funding for Israeli venture capital funds.

Competition for The Multi-National Companies

Competition for The Multi-National Companies

A further competitiveness index of the Israeli ecosystem, and in general of global innovation hubs, is the ability to attract multinational companies to host the operation of significant centers of activity and development. Over time, Israel has been the first place outside the US where a variety of companies have developed a center of activity. As of 2024, there are 515 multinational companies operating in Israel. Together with the growth of other global innovation hubs, competition is also increasing in this arena.

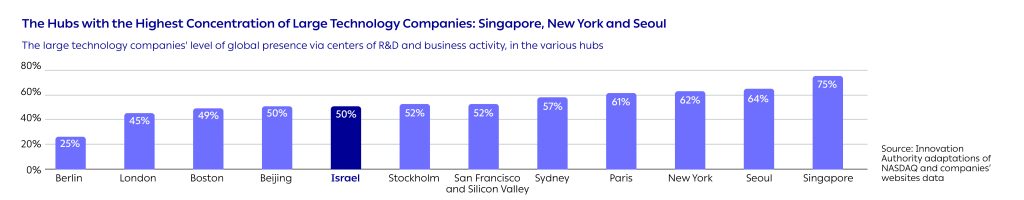

A study conducted by the Innovation Authority aimed to compare different hubs according to the presence of the large global technology companies operating there. To do so, it identified the 56 companies with the highest market value on the NASDAQ that operate in technology fields, as of January 2024. The importance of these companies’ presence in an innovation hub is expressed in several ways. First, their presence is a quality mark for the local hub. Second, these companies are generally stable and significant employers that pay high salaries. Third, work in these companies frequently exposes their employees to the forefront of technology. Next, the study checked in which hubs the listed companies operate in, thereby enabling a comparison between the hubs with a relatively high concentration of large and significant technology companies.

The study reveals that the places with the highest concentration of the largest multinational companies via R&D and business activity centers are not necessarily the largest hubs either in terms of investments in startups or local venture capital funds. The leading hubs in terms of large technology companies’ concentration are Singapore, New York, and Seoul. Furthermore, the study shows that the large technology companies’ level of presence in Israel is similar to that in Boston and Silicon Valley. Further discussion of the subject of competition for the presence of multinational companies in innovation hubs appears below in Issue no. 4.

The Mature Technology Companies: Hubs’ IPOs

The Mature Technology Companies: Hubs’ IPOs

Another index of business activity in startups and innovation hubs is IPO activity that expresses the maturation of growth companies and their transformation into public companies. In overall economic terms, the consolidation of these companies in a hub is of great importance: these are large independent companies that usually employ a relatively large number of people in a variety of roles. They are surrounded by an ecosystem of service providers and they contribute to state revenues via tax payments (of both the employees and the companies themselves).

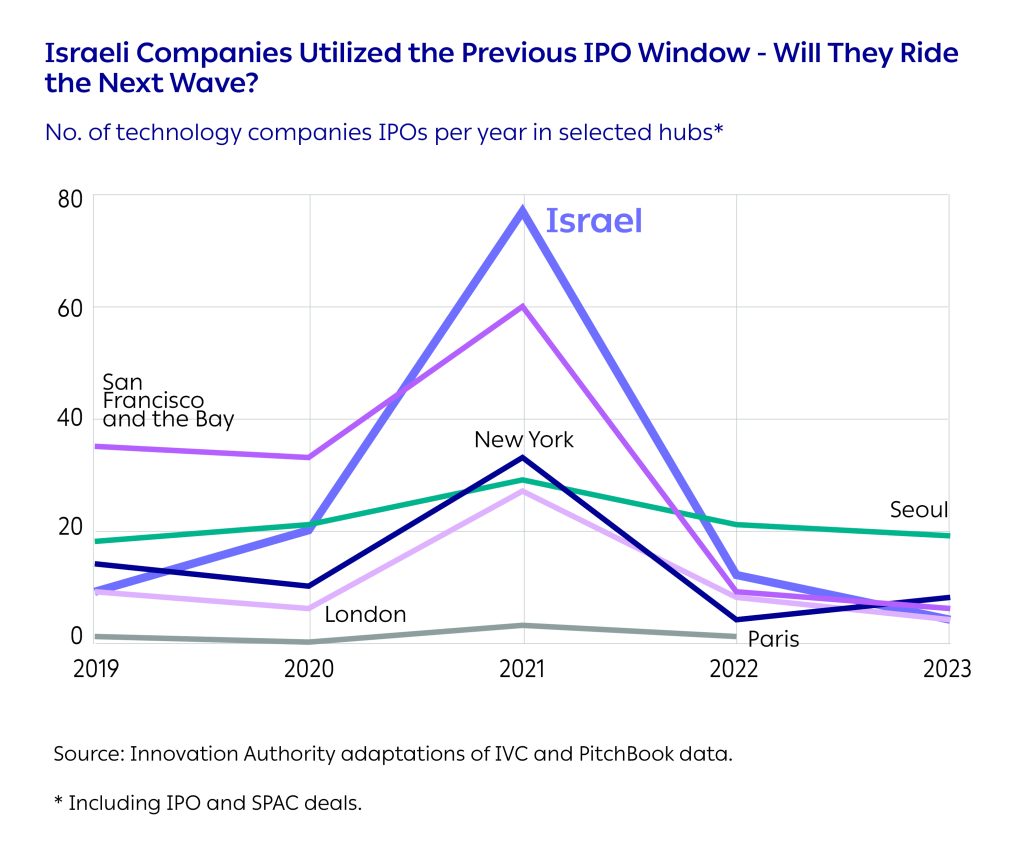

In 2021, the most recent wave of IPOs reached its peak. An examination of technology companies’ IPOs in prominent hubs reveals that over 70 Israeli companies took the opportunity to go public (via SPAC or IPO). This led to Israel overtaking Silicon Valley and New York in terms of IPOs that year. In 2022, the IPO window closed although the number of IPOs in Israel was still second only to Seoul. In 2023, the negative trend continued in most of the hubs (except New York where there was a slight recovery and in Seoul which maintained a similar level throughout this period).

There are signs indicating that the global IPO window for technology companies has re-opened in 2024, one which is characterized by better compatibility of stock valuation and market expectations. The question arises as to whether Israeli technology companies are ready to utilize the window of opportunity. To this end, effort must be made to ensure that government policy creates a business environment that supports Israeli technology companies for the duration of their operation, both before and after going public.

Issue No. 4: The Next Growth Engines of Israeli High-Tech

Considering high-tech’s importance and growing centrality to the Israeli economy, a question exists about the sector’s continued growth in the coming years. When trying to identify the next growth engines of Israeli hightech, it is already possible to detect several long-term processes and trends that are influencing the directions in which Israeli high-tech may develop.

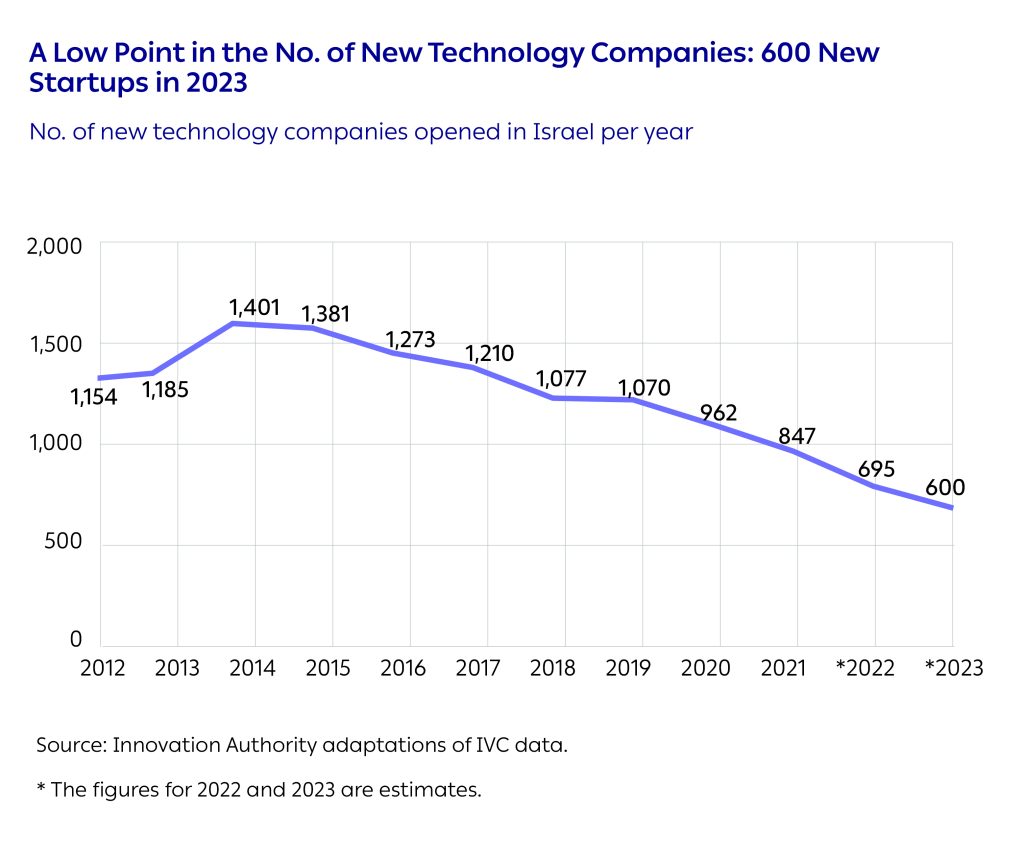

The first of these relates to technological entrepreneurship. Since its inception, Israeli high-tech has relied on groundbreaking innovation via young companies that engage in the development of high-risk technologies. One issue that will influence the sector’s future is related to the “crop” of Israeli startups. Since 2015, there has been a negative trend in the number of new startups established every year. The question arising in this context is if “enough” new technology companies are established each year or whether there is a threat to the future of the “startup nation”. According to a preliminary estimation, only 600 companies were established in 2023, a figure that constitutes a warning sign.2For further details ,see the Authority’s publication on this subject in conjunction with the RISE Institute )formerly SNPI(

Another significant variable, presented in detail below, relates to the funding of companies at different stages, especially early-stage companies – funding that will enable the companies to continue their growth and development until they reach maturity. Additional factors that will impact the hub’s growth direction are also connected to technological diversity, and to the establishment of companies in growing sectors that enjoy global demand, such as Artificial Intelligence.

Additional factors that influence the growth engines of Israeli high-tech will be presented later in this section. These include venture capital funds’ investments in certain fields, multinational companies’ activity, and mature technology companies that are listed and traded on capital markets. Proposals for policy steps that support the growth engines will be presented in relevant cases.

Investments in Startups: A Decline in Investments That Takes Israel Back to 2018

Investments in Startups: A Decline in Investments That Takes Israel Back to 2018

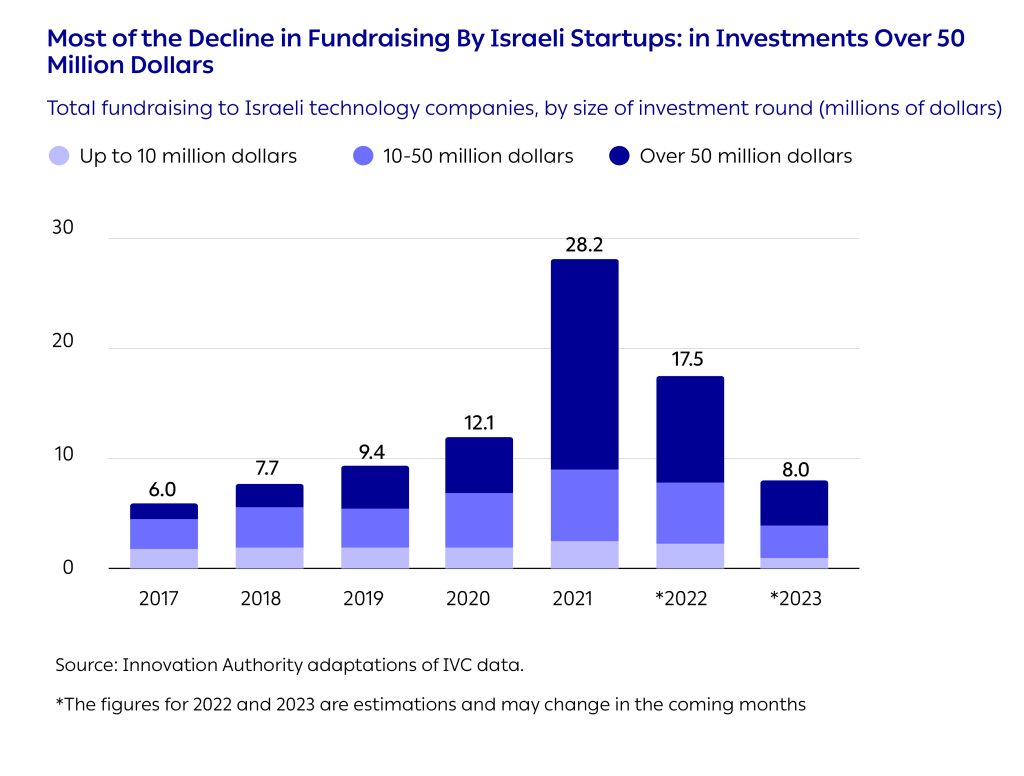

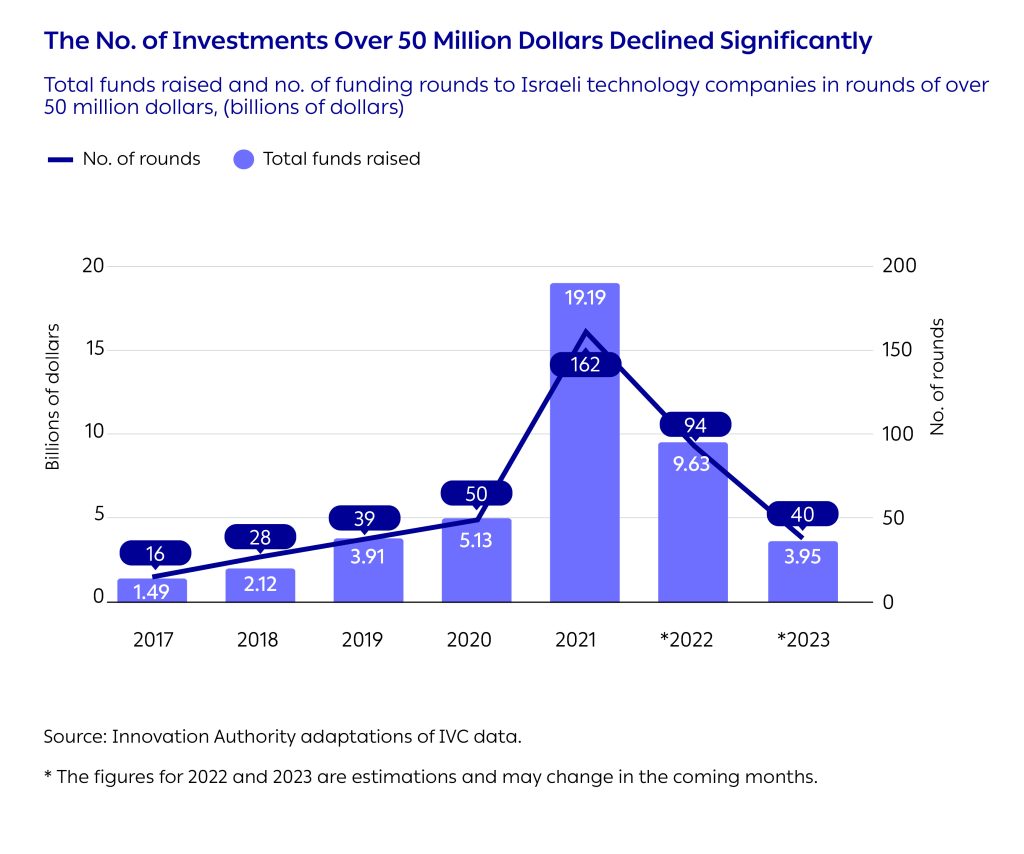

As shown above, since 2011, there has been a negative trend in investments in Israeli startups. Most of this decline was in investments in large funding rounds of over 50 million dollars. These funding rounds fueled the growth of independent and mature Israeli technology companies.

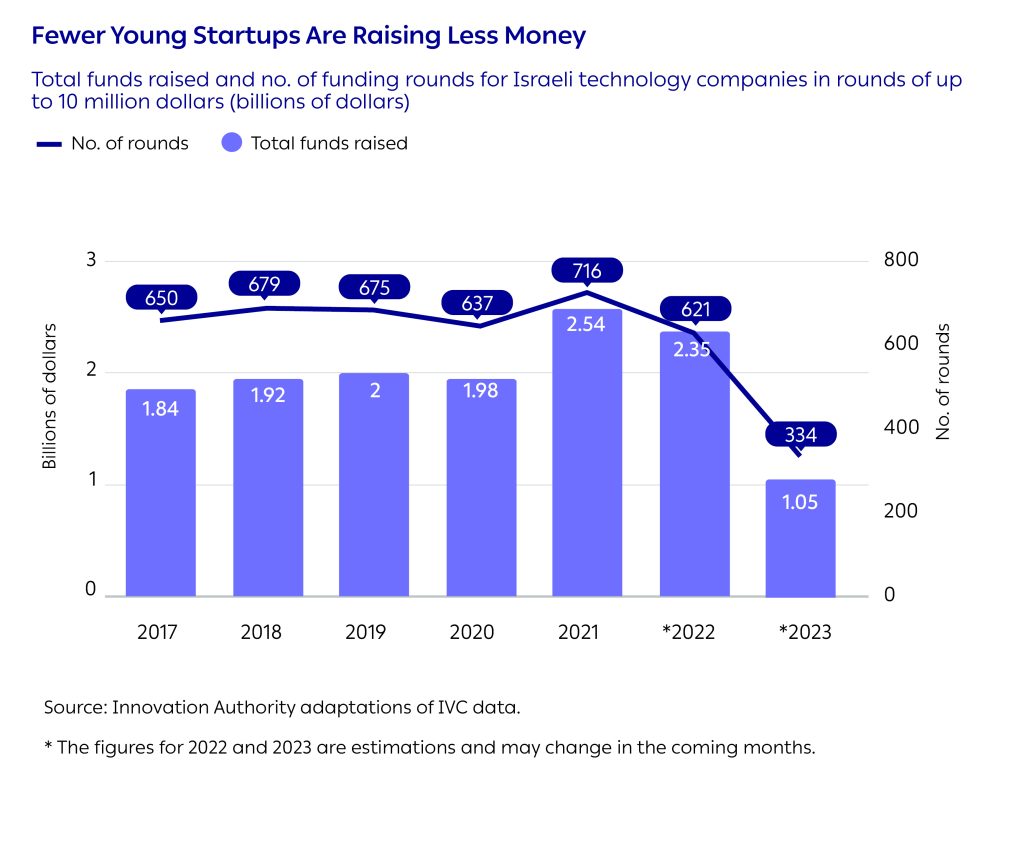

At the same time, there was also a significant decline in early-stage funding rounds. 30% of the total capital raised by Israeli startups in 2017 was raised via investments of less than 10 million dollars. This figure declined to 13% in 2023. The capital invested in the early funding rounds is small, not just in relative terms but also in absolute terms: in 2017, it stood at 1.8 billion dollars and in 2023, less than 1 billion dollars.

Investments in Startups: A Significant Decline in Fundraising by Young Startups

Investments in Startups: A Significant Decline in Fundraising by Young Startups

The data reveals that the significant increase in investments in startups between 2021-2022 did not lead to an increase in early-stage investments, where there was a moderate rise in the capital invested. In other words, the early-stage companies did not benefit from the upturn in investments.

There was also no significant change in the average size of the funding rounds of less than 10 million dollars which increased from 2.8 million dollars in 2017 to 3.1 million dollars in 2023. At the same time, the number of investment rounds in early-stage companies declined in 2023 to half the number registered in 2022.

This means that early-stage startups had less capital at their disposal, thereby possibly making it difficult for startups to reach more advanced stages. Because young startups are the foundation for growing the mature companies of the future decades, a drop in the number of new startups combined with a decline in funding of early stages may lead to a decline in the future growth rate of Israeli high-tech.

In light of this understanding regarding Israeli high-tech and given the long-term importance of startups to the Israeli ecosystem, in 2023 the Innovation Authority offered tools aimed at supporting early-stage companies. Further details on these tools are presented at the end of this part.

Investments in Startups: Most of the Decline in Investments is in the Large Funding Rounds

Investments in Startups: Most of the Decline in Investments is in the Large Funding Rounds

The past decade was characterized by high volatility of the large investments rounds of Israeli startups. In 2017, approximately 25% of the capital raised that year was in rounds of over 50 million dollars. Four years later, this ratio increased to 70% and, after two years of decline, stood at 50% in 2023. This decline explains most of the drop in investments in Israeli technology companies over the past year.

The average size of funding rounds over 50 million dollars in 2023 was similar to that recorded in previous years and stood at 98 million dollars. 2021 was an exceptional year in which the average size of the funding rounds over 50 million dollars stood at 118 million dollars. In other words, the decline was in the scope of deals in these stages, with the number of large funding rounds declining to a level similar to that of 2019.

Advanced-stage Israeli technology companies that have raised large sums in recent years, and which will be required in coming years to find a source of funding to continue their activity, may encounter difficulty in raising capital in large funding rounds given the decline in available capital for these stages. Consequently, they will need to increase revenues and make the transition to profitability in order to finance their activity or to engage in liquidity events (M&A), assume debt, or go public (IPO). Furthermore, some of the companies participating in funding rounds may be required to do so according to a lower value (down round).

Startups’ Expectations: Raising Capital and Down Rounds

Startups’ Expectations: Raising Capital and Down Rounds

The current period, with its security-related events and more, is affecting the general atmosphere in the sector as well as the high-tech companies that are in contact with overseas clients and investors.

One of the questions asked at this time, both in Israel and other global technology hubs, relates to companies that will be required to raise capital at values lower than their previous funding round when the markets were buoyant (a phenomenon known as “Down Round”). To examine the mood among investors, the Innovation Authority asked them in March-April 2024 about their fundraising expectations for the coming year.

The survey reveals that during March-April, 61% of the companies engaged in fundraising estimated that there was a low probability of being able to successfully raise the capital they need, whereas 39% of the companies engaged in fundraising estimated that there was a high probability of being able to do so in the next funding round. In a survey conducted in November-December 2023, closer to October 7, this figure stood at 34%.

Furthermore, 36% of the companies raising funds estimated in March-April 2024 that there was a high probability that their next funding round would be completed at a significantly lower value than their present value. This figure represented no significant change from that recorded in November 2023 when it stood at 39%.

Startups’ Main Challenges: Securing Funding and Global Uncertainty

Startups’ Main Challenges: Securing Funding and Global Uncertainty

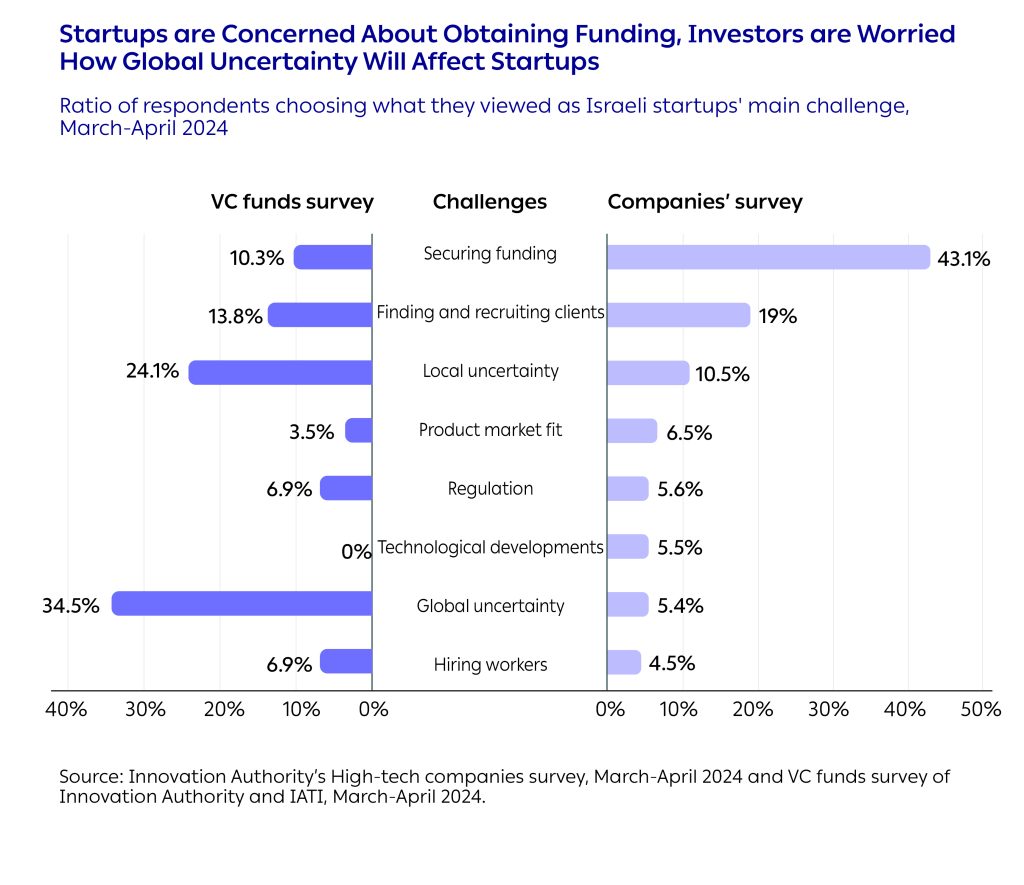

In general, the challenges facing Israeli startups during this period seem no different from those during routine. The central issue occupying 43% of the respondents to the companies’ survey is securing funding. The second challenge, indicated by 19% of the respondents, is finding and recruiting clients.

The survey reveals that between the surveys’ two rounds – November-December 2023 and March-April 2024 – there was a decline in the ratio of respondents who rated securing funding as their main challenge. In contrast, the ratio of respondents who identified the local uncertainty as their main challenge increased.

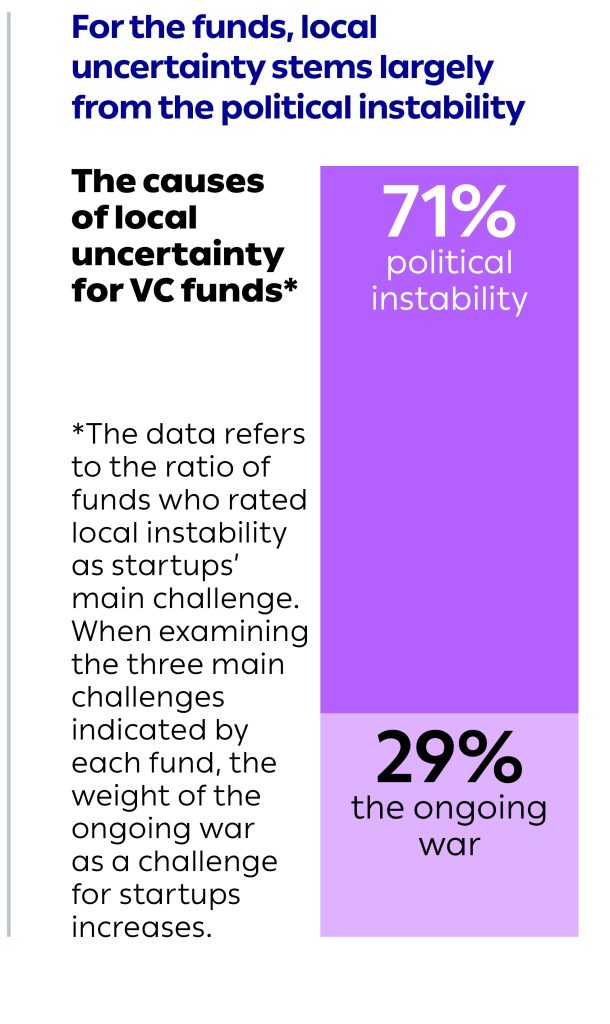

It is interesting to note the differences in the perceptions of investors and startups. Parallel to the companies’ survey conducted by the Innovation Authority in March-April, the Authority and IATI surveyed venture capital funds operating in Israel.3For details regarding the survey’s methodology ,see Appendix 1 When the investors were asked to rate the main challenges facing Israeli startups, 34.5% of them chose global uncertainty while 24% chose local uncertainty. Only 10% indicated securing funding as their main challenge even though this was rated first by the companies themselves. 14% chose the finding and recruitment of clients which was rated second by the companies. In other words, there is no correlation between the challenges as perceived by the companies and by the investors, with each group evaluating the current period’s main challenges differently.

The Next Sectors: What will the Funds Invest in Next?

The Next Sectors: What will the Funds Invest in Next?

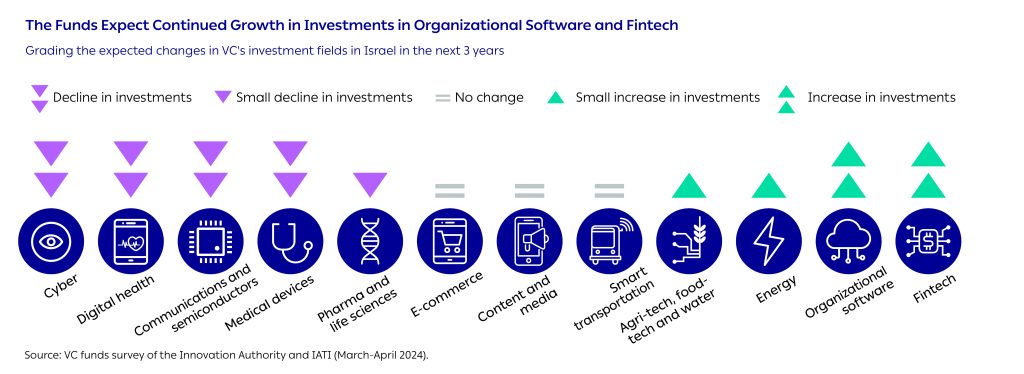

In recent years, investments in Israeli startups have been concentrated in three main fields: organizational software, cyber and fintech. To identify possible changes in the composition of investments in startups, our survey asked the venture capital funds about their expected main fields of investment in the next three years compared to the composition of their current investments.

The survey reveals that the funds estimate that over the next three years, the importance of fintech and organizational software in their investment portfolios will continue to increase. They also expect an increase in in fields related to climate-tech technology, including energy, agri-tech, food-tech and water. In contrast, the funds expected a decline in investments in cyber and in life sciences fields. There are several fields in which they expect no significant change in the scope of investment including smart transportation, content and media, and e-commerce.

The Funds’ Expectations: Fundraising and Transfer of Startups’ Activity Overseas

The Funds’ Expectations: Fundraising and Transfer of Startups’ Activity Overseas

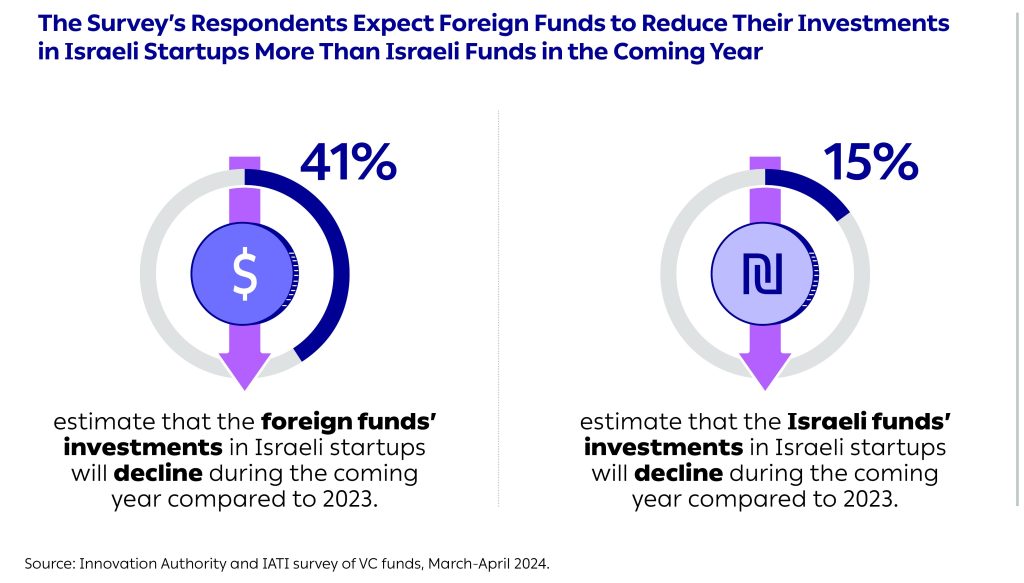

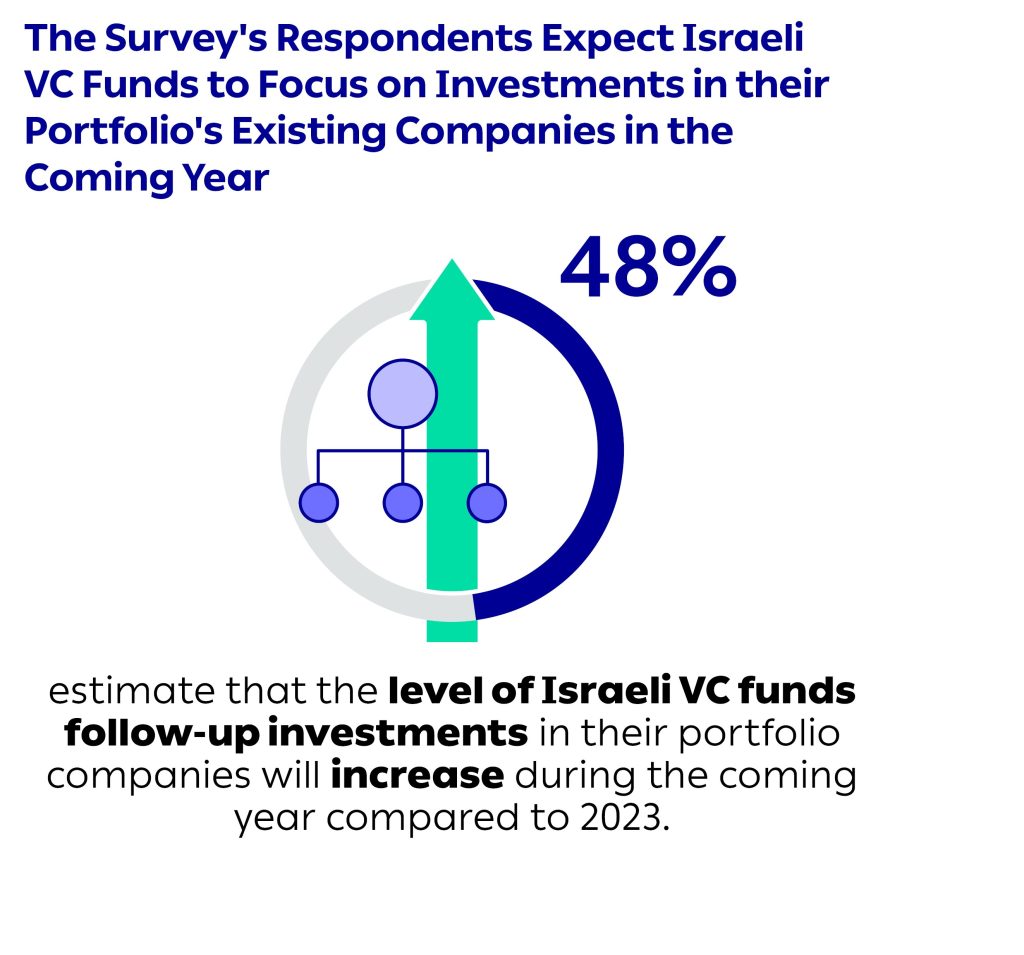

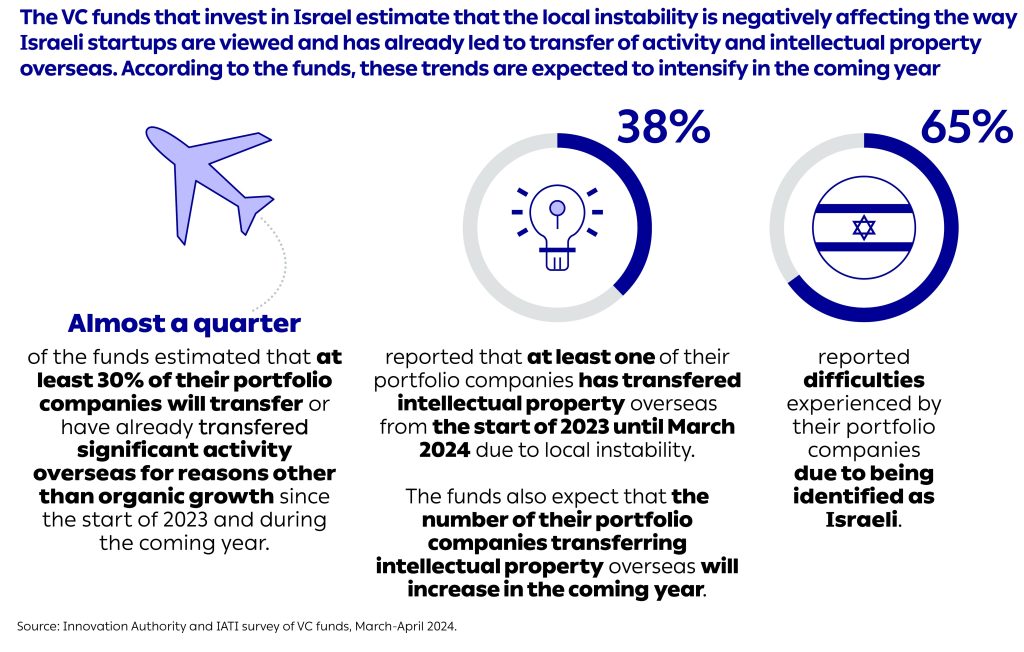

One of the significant factors that will influence the development of startups in the coming years, in terms of the resources at their disposal and their future technological and business directions, is the venture capital funds operating in Israel. As noted, these funds – both local and foreign – invest in startups in various fields and stages.4For more details on the activity of venture capital funds in Israel ,see the Innovation Authority’s publication on this subject in conjunction with KPMG ,IVC and the Gornitzky & Co legal firm. The venture capital funds operating in Israel were asked in the survey about their expectations as to the investment activity of funds in Israel and about the business activity of their portfolio companies. The survey’s results indicate several trends:

The Next Generation: The Early-Stage Startups’ Fields of Activity

The Next Generation: The Early-Stage Startups’ Fields of Activity

A significant factor that will influence the development of Israeli high-tech in the coming years is the future fields of activity of the local high-tech companies. The local ecosystem currently has a competitive advantage in fields that have accumulated knowledge and expertise such as organizational software and cyber, fields related to knowledge originating in IDF technology units. Furthermore, it is necessary to identify the fields that will become pivotal to the future global economy, such as solutions in the field of climate-tech.

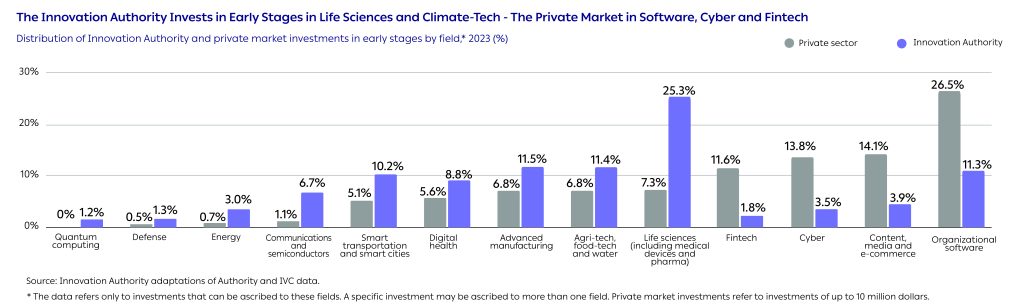

An analysis of the investments in startups funding rounds of up to 10 million dollars reveals that most of the early-stage investments in the private market are in the fields of software (26.5% of the investments up to 10 million dollars are in the field of organizational software). In contrast, state investments in hightech, implemented by the Innovation Authority, are primarily in the fields of life sciences and climate-tech. An examination of the distribution of the Innovation Authority’s investments vis-à-vis the private market’s investments in 2023 reveals that the Innovation Authority invests in fields in which the private market only invests to a small degree.

Over 500 Multinational Companies in Israel

Over 500 Multinational Companies in Israel

Yet another factor that will impact Israeli high-tech in coming years is the presence of multinational companies, the importance of which was presented in the previous section of this report.

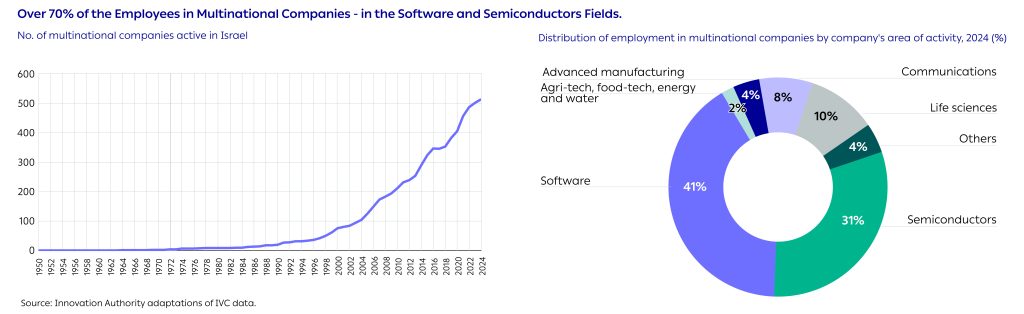

As of 2024, 515 multinational companies are operating in Israel, employing a total of nearly 90,000 people. The multinational companies in Israel currently operate in two main fields: software and semiconductors which account for 72% of the multinational companies’ employees. The field of life sciences comprises 10% of the multinational companies’ employees while 8% are employed in companies in the field of communications.

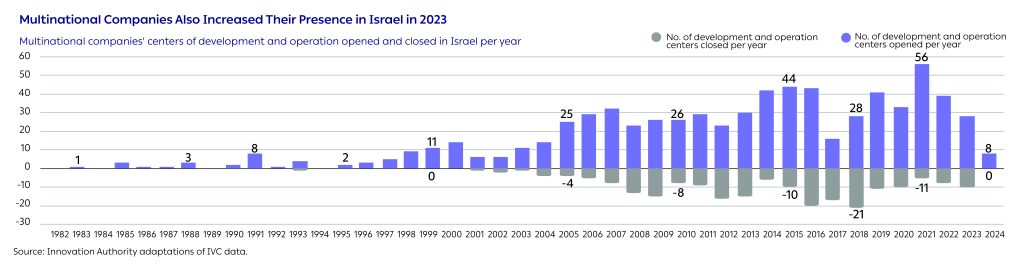

Most of the multinational companies began operating in Israel after the year 2000. In recent years, the number of new centers of activity established each year by multinational companies in Israel has steadily increased. Between 2019-2023, an average of 33 new centers of opetation were established each year. In 2023, the number of new centers declined and stood at only 28.

Over time, 220 such centers have closed in Israel. Despite the downturn in the opening of new centers of operation in 2023, there was not a significant change in the number of centers closing during that year. When examining the future of high-tech and its growth engines, and considering the importance of employment in high-tech for the continued growth and prosperity of the Israeli economy, the question arises of whether the government needs to actively implement a policy that supports the increase of multinational companies in Israel.

One of the characteristics of multinational companies is that their employment multiplier is lower than that of other companies in the high-tech sector and is, in effect, the lowest in the entire sector except for young startups.5For details, see Innovation Authority’s State of High-Tech Report, 2023 For each multinational company employee in a technology role, there is just half an employee in a non-technology role.

Consequently, despite the multinational companies’ great importance to the Israeli ecosystem, there are seemingly no grounds at present for creating a policy to proactively increase their number. Nevertheless, there are grounds for examining any existing obstacles to the activity of significant multinational companies yet to initiate operations in Israel, if they have a potential noteworthy contribution in this country.

Realizing the Growth Potential of the Public Technology Companies in Israel

Realizing the Growth Potential of the Public Technology Companies in Israel

Israeli public technology companies are a significant mainstay of Israeli high-tech. Some of them are important employers, both in technology and non-technology roles, they employ diverse service providers in the Israeli market, operate for an extended period and, unlike startups, sometimes achieve profitability and pay corporate taxes. In general, public technology companies portray the consolidation and maturation of Israeli startups. As a result, in this section we will present the situation report of these companies and discuss the ability to create additional such companies that contribute significantly to the Israeli economy.

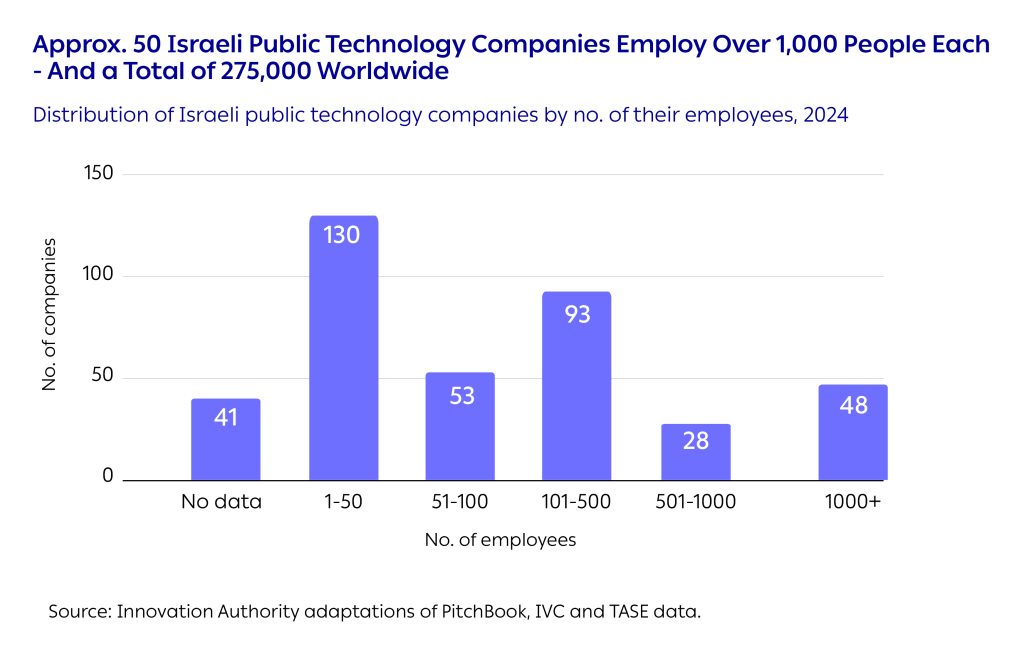

393 Israeli public technology companies are traded on global stock markets. Their cumulative market value, as of April 2024, is 234 billion dollars and they employ 320,000 employees worldwide. An analysis of the public companies according to the number of their employees reveals that already today, there are nearly 50 large Israeli public technology companies with over 1,000 employees which together employ a total of 275,000 people worldwide. The market value of these companies amounted to 184 billion dollars as of April 2024, approximately 79% of the total cumulative market value of all the Israeli public technology companies.

In the next group in terms of size, there are 28 companies with 500-1,000 employees which together employ a total of 20,000 workers. 93 companies have between 50- 100 employees and also employ a total of 20,000. The rest of the companies are smaller and have less than 7,000 employees collectively.

There are between 30-40 public companies in Israel with employees that, together with 90 Israeli unicorns, constitute the main potential for growth and the creation of companies that will become significant employers in the high-tech sector.6Data relating to the number of Israeli unicorns was taken from the Tech-Aviv website.

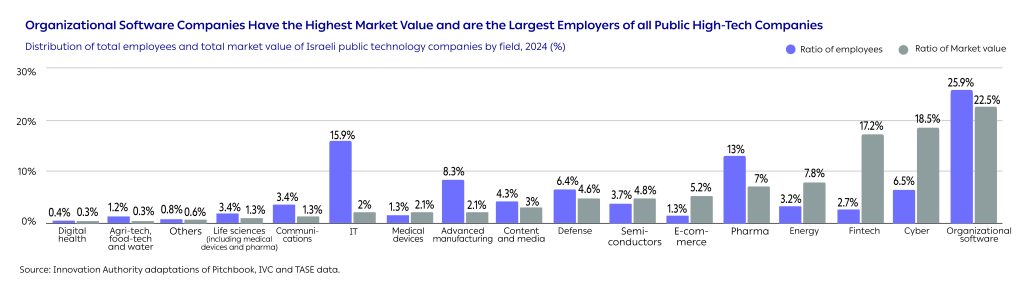

The value of public technology companies is primarily concentrated in three fields: organizational software, fintech, and cyber. Together, these three fields comprise 58% of the market value of Israeli public technology companies. Nevertheless, analysis of the distribution of the employees in the public companies according to fields of activity reveals a slightly different picture to that revealed in an analysis of market value. Although the field of organizational software is the field employing the most employees – approx. 83,000 employees worldwide – the next biggest fields in terms of the number of employees are IT companies that employ 51,000, pharma (42,000), and advanced manufacturing (26,000). In other words, this analysis reveals that there is no correlation between the companies’ market value and their number of employees.

The main contribution of public technology companies to the economy stems from their employees and from the creation of circles of employment as a result of the companies’ local business activity. To encourage the growth of Israeli public high-tech companies, the state must encourage the companies to base as many of their organizational functions as possible in Israel. The diagrams below show that organizational software companies lead both in terms of market value and number of employees, in contrast to cyber and fintech companies which display a high market value but employ a relatively low number of workers. The formulation of government policy relating to high-tech investment must consider the employment potential of different fields, with an emphasis on employment in a variety of roles in Israel.

The Innovation Authority’s Response to Current High-Tech Challenges

The Innovation Authority’s Response to Current High-Tech Challenges

The past year has been tumultuous for the State of Israel, the Israeli economy, and especially for Israeli high-tech. The year has created challenges that have been presented in detail in this report. To contend with them and assist Israeli high-tech to emerge stronger from the current crisis, the Innovation Authority has operated several new programs over recent months:

1. Fast-track Grants for Companies with a Short Runway

Three weeks after the events of October 7, the Innovation Authority and the Ministry of Finance decided to establish the “fast track” that aims to protect early -stage startups that were in the middle of a funding round at the outbreak of the war, that have technological and business assets and which have a short runway of survival of fewer than six months. Companies that submitted requests to the fast track received a response within less than four weeks instead of 11. During the first three months of the fast track’s activity, 247 requests were approved (38% of the total requests submitted), with a total investment of over 1.25 billion shekels. A third of the capital was a direct investment by the Innovation Authority and the remainder by the private market. This program is intended for activation during times of emergency and was also used during the Covid pandemic.

2. Startup Fund for Financing Early-Stage Companies

After providing an immediate response at the beginning of the war via the “Fast Track” program, the Innovation Authority launched the Startup Fund. The fund is aimed at assisting the establishment and financing of early-stage deep-tech companies at various funding rounds while synchronizing with the market. The fund directs its activity at high-risk R&D-oriented fields that have low availability to private capital. The Startup Fund is expected to increase the state’s investment in fields that receive only low private market investment. The Startup Fund had a budget of half a billion shekels in 2024 and is expected to grow in the years to come.

3. Yozma 2.0 Fund for Increasing Israeli Institutional Investment in High-tech

On the eve of Passover 2024, the Innovation Authority launched the Yozma 2.0 Fund that incentivizes investments of institutional entities in Israeli high-tech via investment in Israeli venture capital funds. Like the mechanism activated by the “Yozma” Program in the 1990s, the Innovation Authority will provide an added yield to institutional entities that invest as part of the program. The scope of the incentive will be determined by the technological depth of each fund in which the institutions invest. Investments by the Innovation Authority and the institutional investors as part of the Yozma 2.0 Fund are expected to inject 700 million dollars into Israeli venture capital funds between 2024-2026 – about half the sum that was raised by the funds in 2023. Approximately a quarter of the sum (23%) will be invested by the state via the Innovation Authority. Encouraging Israeli institutional investors to invest in Israeli high-tech is intended to achieve several objectives. First, to increase the short-term availability of capital for Israeli startups, especially during the current period which, as noted in this report, is characterized by a decline in private market investments in Israeli startups; second, to reduce the medium- and long-term dependence of Israeli high-tech on foreign capital, thereby bolstering the stability of the local venture capital market in the face of global upheavals and macro-economic volatility; finally, to encourage the creation of venture capital funds that specialize in the worlds of deep-tech by providing an additional incentive to funds that invest in these technologies

4. Angels’ Clubs Program for Deep Tech

As part of the efforts to increase the capital available for startups during the current period, the Innovation Authority launched the Angels Club program in early 2024. This program aims to increase the number of private investors at the pre-seed and seed stages. The Angels Club enables an aggregate investment of several investors in a company, thereby increasing its chances of success. For the investors, the club enables exposure to a larger number of companies from different sectors and creates a diverse investment portfolio. The Innovation Authority is expected to announce the winners in June 2024. Each club selected is expected to receive 2.7 million shekels for a three-year period.

5. Venture Creation Incubators Program for the Creation of Fledgling Deep-tech Companies

The Innovation Authority’s Technological Incubators program is directed at forming new venture creation-based investment entities via new operational models. These will aim to encourage the establishment of new companies via the integration of leading global players, with an emphasis on deepening industry’s collaboration with academia. In April 2024, the Innovation Authority published a call for proposals for the establishment of three new entities with an investment grant of up to 40 million shekels each for a period of five years. It is important to emphasize that an Innovation Authority investment grant as part of this program is not intended for direct investment in companies but rather, for the operational costs and expenses involved in creating infrastructures to be used by the companies established therein. The program is aimed at creating companies in R&D-oriented fields and also incentivizes the establishment of investment entities that specialize in the worlds of deep-tech.